Chapter 5: The Moderating Influence of Bishop Hills (1860–63)

For all of the amazing tales of the origins and survival of the two remote British colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, huddled together as they were on the far west coast of North America, when this history is viewed from the top down the outcome seems almost predictable. Yet the reality was very different. Even as James Douglas, sustained by the Colonial Office, made the two colonies his own, others, notably Anglican bishop George Hills, provided a moderating influence. By tagging along with Bishop Hills following his arrival in Victoria at the beginning of 1860, four years before Seymour and Kennedy replaced Douglas as the single governor of two colonies, and six years before the two colonies were merged, we get a more nuanced perspective on these two remote colonies’ early years, when their futures were very much in play.

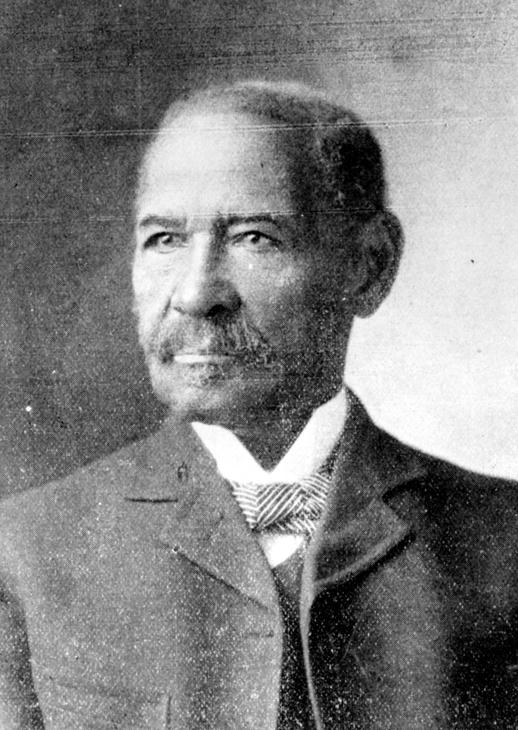

Introducing Bishop Hills

The same day the newly appointed Anglican bishop arrived from England on January 6, 1860, he began a private journal whose opening sentence reads: “We are within a few hours of Victoria.”1 Continuing to write with a similar matter-of-factness, Hills chronicled his attitudes and actions, his feelings and outlook, and by virtue of doing so provides a useful second opinion to the letters that those in charge exchanged with the Colonial Office in London. Whereas James Douglas wrote strategically to persuade others, Hills’s journal was for his eyes only. In consequence, it opens a window on a British Columbia in the making otherwise hidden from view or obscured.

It is also the case that, as with all our accounts, Bishop Hills’s journal tells us only part of the story. “Born into a stern, disciplined naval family,” according to Jean Friesen in The Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Hills earned undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of Durham, followed by two decades of parish work in England before his appointment on January 12, 1859, as the founding Anglican bishop of British Columbia. He was consecrated at Westminster Abbey in London a little over a month later on February 24.2

George Hills was no ordinary appointee. His position was initiated and funded by the very wealthy English heiress and philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts, who oversaw his selection, provided generous financial support, and threw into the arrangement a corrugated iron building to be shipped in pieces around South America to Victoria to become, in 1860, the first consecrated Anglican church in today’s British Columbia, along with a smaller structure to house its bishop.3 In October 1858, with events already in play, the secretary of state for the colonies, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, forwarded to Governor James Douglas “a letter from the Archbishop of Canterbury announcing to me the munificent endowment offered by Miss Burdett-Coutts for the foundation of a See in British Columbia.” In his letter to Lytton, the Archbishop explained the endowment’s impetus in the gold rush:

"In consequence of the importance which is likely to belong to the colony of New Columbia [sic], & the expediency of providing for the spiritual instruction of the population assembling there, Miss Burdett Coutts has empowered me to propose the appointment of a bishop there, who may take the oversight of the Clergy & superintend the religious interest of the country & people; and for that purpose she is prepared to furnish an Endowment of the See, to the amount of £15,000.4

"

To supplement the endowment, Hills during the first ten months of his appointment had raised funds in England, Ireland, and Scotland in the form of five-year pledges to the Columbia Mission, founded to sustain his work in the distant British colony.5

Nor was George Hills without his own needs. In a private letter to British government officials of October 1859, he requested passage “to B. Columbia by the W. India Mail Steamer on the 17th of November” not only for himself but also for “two servants,” being “a man & wife,” Samuel and Jane Bridgman.6 While unmentioned in his journal, they were fundamental to his everyday well-being.

Four fractures

However prepared Hills might have considered himself to be for his big adventure, on his arrival in January 1860, the way of life he had up to then taken for granted would fracture in four important ways, wresting Hills from his assumptions about the way things were and therefore ought to be. These four fractures would cause Hills to bring new eyes, ears, and feelings into play respecting the two British colonies under his watch on behalf of the Church of England.

Hills’s first task on arriving was “to pay my respects to the Governor,” who lived not far from the temporary accommodation that had been found for Hills. For a brief moment he may have hesitated. As to his almost certain reason for doing so, he was already aware that “Mr. Douglas’ wife is a half caste.”7 Meeting her on being invited for dinner, Hills wrote in his journal without further comment: “Dined with the Governor. Met Mrs. Douglas for the first time.”8

Indicative of the biases we all share from time to time, a few days later Hills would similarly differentiate the wife of the couple living next door to him:

"In a neighbouring house is an Indian woman the wife of a respectable white man named Cotsford. She is a nice clean & well ordered person—will not speak but understands English. I saw her little girl a pretty child you would not tell her from an English girl—speaking English well. The other day the mother of Mrs. Cotsford went out at 8 o’clock, got drunk & died at 10. She was placed in a coffin with 15 Blankets. Her head did not lie easy & two new blankets were brought—they put inside a work bag—a looking glass, a box of matches & many such articles.9

"

Thomas Cotsford was an English-born Hudson’s Bay Company employee based at Fort Victoria who had purchased a town lot there in 1854.10 He had a family with Betsy, whose English-born father John Thompson Dunn had arrived at Fort Vancouver with the HBC in 1821. Dunn was well-known as the author of History of the Oregon Territory, published in London in 1844 and for sale into the present day.11 Betsy’s mother was, according to a grandson, “a Russian girl” from today’s Alaska, then a Russian possession.12 The Cotsford daughter who caught Bishop Hills’s eye was six-year-old Harriet, who would in due course marry Scottish-born Donald McKay. Their daughter wed Irishman John Hart, who would become British Columbia’s minister of finance (1917–24 and 1933–47) and premier (1941–47).

The mixed Indigenous and white descent of Amelia Douglas, Betsy Cotsford, and other “half breeds,” as Hills would sometimes term persons of mixed Indigenous and non-Indigenous descent, was the first of four fractures of everyday life, whose racial parameters Hills had up to then either been unaware of or taken for granted.13

A second fracture may have earlier come to Hills’s attention on his being informed that the house prepared for his arrival belonged “to a Coloured man.”14 Possibly not digesting the information at the time, it became visible, along with a third fracture, at Hills’s inaugural church service on January 8 when, he wrote in his journal, “about 42 Communicants were present—among them several coloured people—and a few Indians stood near the door.”15

The fourth fracture upending a familiar status quo alongside racial mixing; “coloured people,” who we now know as Black people; and an everyday Indigenous presence were Chinese men come to mine gold. Hills noted in his journal the presence of “Indians & Chinese as well as miners & labourers & artisans of other nations” at an “open air Mission” run by fellow Anglican priest Alexander Garrett that Hills passed by on his way home from holding services.16

Six days later Hills crossed the Strait of Georgia, which separates Vancouver Island from the mainland by a three-and-three-quarter–hour water voyage, in order to preach there. His journal recorded without further comment “two young Chinese—three Coloured men & others” turning up at his Sunday afternoon service.17 Three days later Hills helped to inaugurate Trinity Anglican Church in New Westminster where Douglas, who had earlier laid the cornerstone, was received by a guard of Royal Engineers, and by their head Richard Clement Moody, at a service that was widely attended, including by “about 300 Chinese, Indians & other nations.”18

Individuals who those in charge may have perceived as fractures sought in their everyday lives to get on equitably with those around them, and it was up to Hills and others identifying themselves as white to decide whether they were permitted to belong.

Initially Hills likely viewed the four fractures mostly in passing, not unexpectedly so given how much he had to absorb in the everyday. It took him a very short time to be made aware of “much rivalry between the two British colonies,” this on learning from a British Columbia resident “how anxious the people are in that Colony that I should come and live there” rather than remain in Victoria and only visit the mainland.19 As for how Hills fared: following a few days of milk being delivered to the accommodation provided for him, “no one came & no milk was there to be had,” whereupon he discovered respecting the milkman that, “as he was a Roman Catholic he could not think of supplying milk to a Bishop of the Church of England!”20

Visiting Freezy

In mid-January 1860 Hills was put in closer contact with Indigenous life on being introduced to the indomitable Freezy.21 “Mr. Pemberton, the Magistrate, & Mr. Cridge accompanied me to the Indian reserve on the Esquimalt side of the Harbour,” Hills wrote in his journal. “We happened on our road to meet the chief of one tribe—the Songish [Songhees]—his name is ‘Freesy.’”22 Joseph Despard Pemberton, grandson of a Lord Mayer of Dublin, was a surveyor, and Cambridge University–educated Edward Cridge was rector at Anglican Christ Church in Victoria.23 The meeting was followed by a formal visit to Freezy’s abode:

"I was placed in the middle as the Tyhee or chief. Presently more came in…These were Freesy’s Councillers…Mr. Pemberton was interpreter—the language was Chinook—or rather Jargon, for it is no language—only a trading medium composed of words of different language & cant terms.

Mr. Pemberton explained to them that I was a King George or English Tyhee & that I was come to endeavor to do them good…

They spoke several times in reply & said they were glad anyone would be their friend and do them good & they would like to be better educated & have better houses. They had heard it said they were going to be removed—this grieved them much. What could they do if sent away—now they could get work & dollars & food but if sent away they must starve…Freesy was dressed in coat & trousers & if seen in England would be taken for rather a shabby Irishman. The others had blankets wrapped round them.24

From the Songish [Songhees] Indians I went to the Northern Indian Encampment. They are the Chymsyan [Tsimshian] from Fort Simpson & the Hydas [Haidas] from Queen Charlottes Island. They are a finer & fairer race then the Songish. Some of the faces were no darker than my own & had a healthy tint on the cheeks.25

"

As Hills’s early journal entries indicate, physical features and skin tones mattered to him, but were at the same time not determinants of his actions and outlook. Hills would become fluent in the Pacific Northwest trading jargon of Chinook, comprised of words from English and French along with Indigenous languages.26 It was expected that anyone in ongoing contact with Indigenous people would be familiar with the jargon, be it the governor of the colony, the Anglican bishop, or an everyday Indigenous person.

Getting to know his new home

There was much to learn, and Hills was keen to do so, often from different perspectives than Douglas or the others who had by now come to accept the way things were. Visiting New Westminster in mid-February 1860, Hills was impressed by its location “on the slope of a hill,” with “about 400 people…in addition to the 300 at the Camp” of the Royal Engineers, dispatched from England to assist the mainland colony’s beginning.

From there Hills and a fellow Anglican minister walked about five miles along a track “just cut out of the mighty Forest…through profuse vegetation, on either side of lofty Pines of 150 to 250 feet high towards Burrards Inlet,” which “is to be the naval Harbour” and would become the city centre of today’s Vancouver. Indicative of the changing times already in view, on one side of where the two clerics walked, “a farmer from Canada was clearing his lot & I doubt not another year will show a plentiful harvest.” On the other side was an Indigenous village where the chief’s house had been built “with a gable roof in imitation of the house of Col. Moody,” the head of the Royal Engineers.27

Crossing over the river by canoe, Hills described in his journal how, outside of the house of “Chief Tschymānā,” who was not at home, one of his “three wives” was caring for her baby, “about six months old—a fine boy bound head & foot like a mummy & upon his head the heavy bandage for the flattening process…suspended in a horizontal position to the end of a bent stick placed in the ground & was rocked with a string.”28 The past, present, and future could not have been more intimately intertwined.

Hills would interact as need be with other religious denominations and was also keen on Indigenous conversion. He was respectful, if to some extent disconcerted, as to how “French priests have been instructing the Indians.”29 Not viewing other denominations as competitors, Hills did not give them much space in his journal.

“The colour question”

The next while passed in a similar fashion to what had gone on before, except that Hills repeatedly found himself faced with what he termed in his journal “the colour question,” which centred on whether “no distinction is to be made in the seating of White & Coloured people” in church or whether to acknowledge Americans’ “abhorrence of sitting next to a [derogatory term for a Black person] anywhere!”30 An English friend who Hills invited to dine in early May told of how he had “mentioned to some Americans yesterday he was going to Church, they said, ‘oh do you wish to go to a place where they will put a [derogatory term for a Black person] along side of you?’”31

Given Governor James Douglas sometimes dropped in for a chat, Hills was almost certainly aware of how he had three years earlier facilitated, at their request, a group of Black immigrants in their move north from California to Vancouver Island. Now Hills found himself similarly acting as an intermediary of sorts.32 Discussing “the colour question” with the fairly recently arrived Trutches—he an Englishman involved in road construction, his wife, in Hills’s words, “an American though I should not have known it”—Hills was perturbed. Trutch “confessed he had objection to sit near some black people, not that he felt any unkind sentiment, but because of the peculiar odour,” while his wife was, in Hills’s words, “patronizing with pity rather than honour & respect as fellow mortals & equal in the sight of God.”33

Three days later, “Mr. Papeus came to tell me the troubles of the Coloured people.” Many had come expecting to find peace from the bitter prejudice in the United States, and Hills was himself caught up in this saga of “injustice which exists against them in America. They are fearful they shall not be free even on British soil. They are all very sad about things which have recently happened.” Papeus described events of the past week:

"A merchant (Mr. Little) sent his daughter to the Female school of the Roman Cath. Sisters. There were at it also some seven or eight Coloured children, among which the niece of Mr. Papeus a girl of 14. Mr. Little informed the Sisters that all the white children would be taken away unless a separation was made. The Sisters had thereupon set up a separate Room for the Coloured children. Upon this the Coloured children have been withdrawn & the parents are in perplexity where to send them…I told Mr. Papeus he might rely upon it the Anglican Church would never make any distinction…

He thanked me with tears for the Consolation he said I had given him—for all these things had made him nervous & very sad. For if on British soil rest & peace & justice to the Coloured people were not to be had where else in the world could they look?34

"

The colour question would follow Hills. Five days later “a respectable Coloured person Mrs. Washington called on me,” concerned as to how “she is a Communicant, but had felt an intruder, not having been…recognized by the Clergyman.” Asked by Hills what she considered to be “the ground of the American prejudice against the Coloured race,” she impressed him with her response. She had heard that some consider the African race an inferior one, but “some of her race were quite white & yet the same prejudice existed against them,” and “she believed they were afraid the race would become more powerful & therefore had to keep them down.”35

By now viewed as an intermediary, three days later Hills was visited by “two Coloured gentlemen,” businessmen Mifflin Gibbs and Jacob Francis, who explained to him how, “as soon as this Colony was formed & before any idea the gold existed they had come here to be in quiet & to find rest.” Now they were caught up in “the prejudice against their race” that “is ever more bitter than in some of the States of America.” Among other actions, “the Coloured people had been excluded from the Philharmonic and the young men’s Xtian [Christian] association,” as well as churches, each of which, they were told, “made its own regulations.”36

Soon Hills was himself caught up. He invited to dinner a New Yorker briefly in Victoria who he knew from his travels. Hills’s guest had earlier attended an Anglican service and “was much surprised to see the Coloured people sitting in all parts of the Church & spoke of it as something quite wrong.” When Hills asked why this surprised him, “he said ‘their colour’ showed it was not right & they had not been made equal to the white nor had they advanced even to equality & therefore it was not intended they should be equal.” Not convinced by Hills’s “obvious answers,” his guest continued, “If you allow them this equality how can you prevent amalgamation—there would be intermarriages.” From Hills’s perspective, so he wrote in his journal: “This caste prejudice [underlining in original] the Gospel entirely opposes & a pure Xtianity must have more effect upon the Americans than at present if this unhappy prejudice is to be rooted out.”37

What to do? How to act? There were no easy answers, or perhaps no answers at all, so Hills pondered over the next weeks and months.

Even as Hills did so, on April 9, 1860, his future was set in stone, or rather in iron, with the news of “the Iron House taken this day out of the warehouse & deposited on the 5 lot on Vancouver St ready for erection.”38 The physical manifestation of Hills having committed short months earlier to this far distant place was about to appear in the form of the first consecrated Anglican Church in what is now British Columbia, soon to be designated a cathedral, alongside an adjacent iron structure, “the Bishops residence,” into which he moved.39 There was no turning back.

In the business of saving souls

As Hills was soon made aware, his business of saving souls across the two British colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia had its complexities. In early June 1860 at Hope in the Fraser Valley, Hills recorded in his journal:

"Had a conversation with a man named Yates—a servant of the Hudsons Bay C. 11 years in their employment. Speaks the native language. Lives with an Indian woman & has a child. Is not married. Defends the unmarried state as happier. Has known instances where men have been married & of unhappiness resulting. A French Canadian at the instigation of the Priest was married. His wife took advantage of his being bound to her & resorted to many of her own ways which from fear of dismissal, before she had abstained from.40

"

Yates’s perspective disputed Hills’s easy assumption that sexual relations were to occur only within Christian marriage, preferably with someone of the same skin colour. Yates was not a heathen and so could not be excused for lack of understanding. “He came from Orkney—was a Methodist. Attends the Methodist Chapel here.” Hills persevered:

"I asked if he would be comfortable to live in an unmarried state in his own country. He said there was a great difference. There were Churches in Orkney & white women. I shewed him that the sin was the same here as in Britain. He allowed it was not right—but said he had been very comfortable.41

"

The end result of Hills’s conversation with Yates was likely a standoff. A similar encounter a month later on the same trip may have had more direct consequences:

"About 10 or 12 miles from Lytton is Spitlums flat, a place where mining goes on. I called in at a store, the only one, it was kept by a Dane who lives there with an Indian wife. He has been many years in the country. At this place the prices were:

"

Flour 23$ per 100 lb 11d/ ½ p lb. 13$/5 per stone Bacon 45c per lb42

Less than a year later, on May 18, 1861, Frank Gottfried, who had been born in Copenhagen in about 1824, would be married at Spitlums flat to Susanna, described as a Lillooet woman whose Indigenous name was Kekachunchalee according to her son Frank Gottfriedson—the addition of “son” to a male offspring’s surname being commonplace in Denmark.43 The officiant at the wedding was the Anglican priest at nearby Lillooet, University of Edinburgh–educated Robert Lundin Brown, who had arrived in British Columbia in 1860 and was immediately posted there.44

An array of learning experiences

Bishop Hills’s array of learning experiences mattered to him, just as they do to our understanding of British Columbia as it was so long ago. Over the course of his inaugural May to August 1860 road trip, Hills, as he related in his journal, introduced himself and preached to both newcomers and Indigenous peoples, sometimes using an interpreter with the latter group, and at other times trying out his growing familiarity with Indigenous languages.45

Encountering at the end of June near Boston Bar “a miner from California with a Revolver on one side and a Bowie knife on the other,” Hills began a conversation, to be informed by the miner “how they [the weapons] were needed in California but not here.” Hills reflected that the difference between California and the British Columbia colony was “all classes are well treated. Chinamen, Indians & Blacks have justice as equal as to others. Indeed it is evident that what the Californian looked for as a sign of high spirit & courage he is now ashamed of.”46

A day later, approaching a bridge over a creek “for which according to a notice 25.c or 1 1/0 was charged for foot passengers, a dollar for a mule or horse,” Hills was pleasantly surprised by how, “on the arrival of my party 6 on foot & two horses—the Chinaman in charge refused to take anything.” Through “much talk” with Ah Fah, Hills learned how “an American had placed over the river…a sort of bridge,” for which to cross “he charged everybody high & when the poor Chinamen came with no money he would take their mining implements.” The magistrate at Lytton had thereupon advised the Chinese men to make their own bridge, whereupon the American sold his right to charge a fee to Ah Fah.47

Coming the next day, June 29, to a larger bridge, “a Chinaman, named Ah Soo,” similarly did not charge them. “No Englishman he said pays to go over the bridge & no poor Chinaman…He charges Boston man (American). ‘Boston man charges Chinaman very high in Californy—Chinaman now charges Boston man ha ha.’”48

In a section of his daily journal Hills headed “British soil a welcome home for all races,” he made three general points in quick succession respecting what he had learned so far on the trip. He first noted how, based on an estimate he was given, three thousand or so Chinese men “are selling out their mining claims in California to come up here & are purchasing claims of the white miners.” Second and third:

"The Indian race is comparatively happy here. Every where King George men (English) are looked upon as their friends. They come & shake hands & hang about us. What a contrast to the constant massacre in the American Territory. A third race badly treated by the Americans is the African. Here everywhere they are treated fairly. Thus in these three instances is British soil a welcome Home.49

"

Hills’s understandings continued to grow. In August 1860, by which time Hills was on his way back to Vancouver Island and staying with Major Moody at the Royal Engineers’ enclave at Sapperton near New Westminster, “Taschclak an Indian came to see me, shewed me a paper in which he promises to be sober.”50 The next day he returned:

"Taschclak came to day again & brought his two wives—Tsahtsalote and Khalowit & his two boys Malasleton & Karkaywile. One wife looked a dozen years older than the other. The elder had 11 rings, the younger 10 rings on the hands. He had had 8 children by his two wives. Had lost six…He told me he endeavoured to bring up his children peaceably & would not let them steal. He said he never got angry & gave himself otherwise an excellent character, with which his wives agreed. He concluded by asking for a bit of paper with some writing on it. The two women were extremely well behaved. Their heads were nicely covered & their hair braided they had one each a comfortable English Shawl & were dressed in coloured cotton gowns as country people in England.

Tashclak said he should be very glad if his children could be instructed. I spoke to them about God & the work of Xt [Christ].51

"

That day being a Sunday, it had another critical component, which was “preaching to Indians at Hope.” Doing so gave Hills an opportunity to try out in his sermon the new language skills he had been acquiring since he began missionizing in the two British colonies:

"At about ½ past 3 Indians began to assemble and soon filled the place, a large store. Several White men also came in. Old Pa-hallak was in his place. I explained to the white persons my desire to instruct the Indians & leave an impression of one or two chief points…

I then addressed the Indians. Many of them knew the Thompson Dialect. So with Chinook, with Kookptchin, with Lillooet, & some Cowichan. I managed to speak to them for nearly an hour. There was much attention. Occasionally some would repeat to others in their own words what I said.52

"

Hills reflecting on what he had learned

As indicated by his journal entries, Bishop Hills had during the summer of 1860 no ordinary adventure: “I have travelled during the 12 weeks upwards of 800 miles—in Steamboat, Canoe, horseback & on foot…I have found myself able to walk nearly 20 miles a day.” Not only that, “I have learnt to sleep as soundly upon the floor of a log hut, or on the ground, as in a bed, to wake refreshed & thankful. I clean my own shoes, wash my clothes, make my bed, attend to horses, pitch tents & all such matters have become easy duties.”53

Consequent on “the last three months of journeyings & perils by land & by water amidst a strangely mixed & peculiar population, my belief in the progress of the Colony has been confirmed.” From Hills’s perspective, “nothing would have opened this tract except its mineral produce,” with “the formation of roads” being the means for realizing the colony’s potential. Hills was intrigued by, and respectful of, the diverse nature of the population that had arrived during the gold rush:

"Variety of race is a remarkable feature & a difficulty in dealing with the population in this country. The Christianity of England is the last known even amongst those who would not pay disrespect to religion. French, Spaniards, Italians, Mexicans & some Germans & Irish are mostly Roman Catholics…Germans, most Americans, & Scotch are Presbyterian or Congregational, or Unitarian…Yet they are the truth of the people.54

"

Despite Hills’s growing understandings, all was not well. From a solely religious perspective he was beside himself:

"The state of religion is as low as it can possibly be amongst civilized people. There is no recognition of it. Sunday is a day of business & pleasure & reveling. Most of the mining class are open profaners of the name of God & many are what are called “free thinkers.” Morals I fear are as far from what is right as the case of religion…

We complain in England of the little hold religion has upon many of the Artisan Class,…but I never met with anything at all approaching the calculating & matter of fact infidelity which prevails amongst many who have been trained in America. They seemed to have had full license to pursue every unfaithful thought & seem to have been unreached by any witness or influence of truth.55

"

Hills was all the same accepting of what was. As to the reason:

"Yet with all this, there is a kindness…in the American miner which is a great contrast to any thing amongst Englishmen. I was everywhere kindly received & in some cases I believe welcomed for religious sake. Allowance must be given no doubt for the frontier life which many of these have led & the absence of all opportunities of grace. But the state of religion is nevertheless a phase of work before us which is not to be seen elsewhere in a British territory & which calls for special exertion, patience & Prayer.56

"

Expanding obligations and new complexities

“Glad to find myself in my own cottage,” Bishop Hills wrote on his return to Victoria in August 1860.57 The two British colonies over which he had oversight on behalf of the Church of England were large in size and also in opportunities. Interracial unions, Black, Chinese and Indigenous peoples no longer challenged Hills’s familiar way of life, but were accepted as part of the way things were.

In mid-August Hills spoke to a group of “Chymsean” (Tsimshian) “in Chinook which many understood,” but which was “more fully interpreted in Chymsean.” Hills then visited the Haida camp, where he despaired at “some of the women decked out in every sort of vulgar finery—even to the wearing of crinoline & hoops,” deemed by him “the unmarried wives of white men—& worse instances were there than even this.”58

Hills’s patience had its limits, especially when it came to religious denominations he had come to perceive as competition. While on Saltspring Island in the beginning of September 1860, “an old chief came on board” the vessel Hills was on with “a chain round his neck on which was appended a crucifix.” Hills lamented in his daily journal how “I wish I had something to give these poor creatures…instead of Romish toys—and yet how much better to give them the treasure which rust & moth do not corrupt, but they are like children & Rome deals with them as such.”59

As Hills was soon made aware, it was not so much a matter of Indigenous people being taken in by others’ religious beliefs as it was their using what was offered them as strategically as possible. Later the same day, Hills was invited into a lodge in which was hanging “the Catholic Ladder,” being “a representation of events of the Bible & the Church,” which, he was informed, depicted how “Americans all went to the flames, but King George men went the right way.”60 “King George men,” being Englishmen, had a pass into heaven.

A few days later, “Mr. Richardson, a Coloured person” Hills had met earlier, invited him to visit the “Ganges Harbour Settlement” on Saltspring, where there were “a good many Coloured people” whose “clearings compare with those of others.”61 As explained by historian Crawford Killian, early on “a considerable number of Black pioneers seized the opportunity to pre-empt land on Saltspring Island” to become an enduring community there.62

At the consecration a week later of a new Anglican church in Victoria, “two coloured gentlemen” were among the fifty invited.63 Indicative of the range of contacts Hills nurtured, he had only just returned when “Freesy, chief of the Songhees asked me to preach” at the “Indian school on the Reserve” on Sunday, September 16.64 A week later Hills gave an invited talk respecting “the profligate condition of the population,” by whom he meant Indigenous women. “The road to Esquimalt on Sunday is lined with the poor Indian women offering to sell themselves to the white men passersby—& instances are to be seen of open bargaining.” A fellow Anglican cleric had earlier described to Hills “houses where girls of not more than 12 are taken in at night & turned out in the morning—like cattle.”65

For all that Hills by his actions sometimes treaded close to the sensibilities line for appropriate behaviour, it was only at the beginning of October 1860 that, it appears, the consequences became public. On October 4 “a respectable trader” chose not to subscribe to his local Anglican church, due to his having “heard that the Bishop had invited Mr. Lester (a Coloured gentleman) to luncheon on the day of Consecration” of the new church.66 Peter Lester was a Victoria businessman.

Back to the everyday

Bishop Hills proudly reported in his journal on November 1, 1860: “A Turnip taken up in my garden (white) weighs 25 lbs & is 42 ½ inches in circumference.”67 Whoever we are, however important we might be or think we are, some of our greatest accomplishments and pleasures are particular to ourselves in our place of being, which Victoria had become for him.

Countering the everydayness of that pleasure was another encounter in his principal business of saving souls. Hills was again educated by Indigenous women respecting that side of the gender equation: “Two women complained in December 1860 of the treatment they receive from Americans. They say evil men come & steal away even the wives in the face of their husbands for evil purpose. They struggle & they cry but frequently it is of no avail.” Likely for lack of options, Hills “told them to appeal to the English Magistrate he could be their friend & not allow such conduct.”68 This minimal advice did not indicate a lack of empathy, Hills having written reflectively and admiringly during his canoe trip earlier in the year:

"The Indian women take a full share of labour. Even more is carried by them than by men. They were paddling with as much strength. One woman was steering a canoe and came close to us. Indeed we passed it. She had 3 silver rings on two fingers of her left hand—& six bracelets. They have earrings also & sometimes anclets. These ornaments are made out of silver dollars.69

"

As Hills had by now come to realize, while he could not as a preacher be everything to everyone all the time, it did not mean he should not try to be so. And by virtue of Hills acting as he did toward persons of mixed descent, Black and Chinese people, Indigenous peoples, and others, they belonged or almost so, at least in the moment. Bishop Hills’s moderating presence accommodated diversity.

Entertaining Lady Franklin

Soon taking centre stage for Bishop Hills was a wholly other experience initiated by the arrival in Victoria on February 22, 1861, of “the widow of the celebrated Arctic navigator” Sir John Franklin, who had disappeared in 1847 on an expedition in search of a Northwest Passage across northern North America. Sixty-eight-year-old Jane, Lady Franklin, had devoted herself to finding out as much as she could about his fate, and she came to Vancouver Island to meet with an old friend who had helped search for Franklin and was now involved with marking out the boundary line between Britain and the United States. Lady Franklin’s purpose neatly coincided with a request by Angela Burdett-Coutts for her to check up on Hills so as to determine how the mission she had funded was getting on.

Lady Franklin was accompanied by her personal maid, in the person of her husband’s forty-four-year-old niece, Sophia Cracroft, whose detailed account of the trip in letters home to England have fortunately survived.70 Her candid descriptions of a Victoria and British Columbia in the making complement Bishop Hills’s journal entries with the perspectives of two very intelligent and perceptive women. The following excerpts, evocative of time and place, are taken from the letters:

"Sunday, Feb 24, 1861. We…entered Victoria about 3–30—glad to get to our lodging, the very best in the place & really very [italics in original] tolerable—a tidy little sitting room & bedroom behind for my Aunt—the landlady giving up her own room to me.

It is kept by a coloured man & his wife…They are very respectable people. He is a hair cutter & has a shop…& his wife has the reputation of being a first rate cook. They are probably one generation if not farther from being the pure Negro, & Mr Moses [born in Britain71] calls himself an Englishman, which of course he is politically & therefore justly. She is a queer being, wears long sweeping gown without crinoline—moves slowly & has a sort of stately way (in intention at least) which is very amusing. Sometimes she ties a coloured handkerchief round her head like the American negroes (she is from Baltimore) but on Sunday she wore a sort of half cap with lace falling behind, her hair being long enough to be parted. The language of both is very good…

As we were emerging from the back of our ‘express waggon’ at Mr Moses’ door, the Bishop passed down the other side of the street, & came to us to welcome us to Victoria…After a short walk over plank side walks, we found ourselves within the [italics in original] iron church brought out by the Bishop, forming (I think [italics in original], but am not quite sure) part of Miss Coutts’ provision for the Diocese. The skin [italics in original] only is iron; it is lined with wood, the pieces being placed diagonally on the walls with excellent effect…The cold was very painful in spite of a blazing stove, and the easterly gale roared and clattered so loud that sometimes we could hardly hear the preacher, tho’ a clearer voice there could not be…

Monday, February 25. The Bishop called early & paid us a long visit which was full of interest. He is a most fortunate man in being thus early in the field, while the colony is in absolute infancy—& in the clergy by whom he works…It is said that he has shewn singular tact & wisdom, and that thus he has gained over most influential persons who were disposed to oppose him…This was the case with the Governor, a Hudson Bay Cos officer of longstanding—but he is now openly desirous of assisting the Bishop to the utmost…

As might be expected, one element in the motley population of Vancouver’s Island, is the negro, or coloured class—the term “coloured” is not applied to the Indian, but only the negro race. You know that everywhere in America, they were treated as unworthy to be in contact with whites except as utterly inferior beings. They have separate churches & separate schools & the mixture of races which is often pointed out to you in the American common schools never includes the negro. The same exclusive system was attempted to be introduced here in consequence of the American prejudice—the Americans threated to withhold their children from the schools if the coloured children remained. The Romanists yielded—so also the Independents…The same feud was excited in Church schools, but the Bishop was not likely to give way upon such a point, and his firmness met with its reward—the threatened withdrawal of the other scholars never took place, and saw the unmistakable descendants of negroes…side by side with the English and American girls…

Another difficulty the Bishop encountered was with the Jews attending the schools. The basis of the teaching is essentially Christian, and no pupil is exempt…This however did not satisfy the Jews who are pretty numerous here…the parents threatened to remove them. The Bishop would not consent…& again he gained all by firmness, for they were not removed…Remember that all this has been accomplished within one year…

Mr. Douglas is the Governor…His wife is a half caste Indian, and he has 6 children of whom Mrs Dallas is the 2nd…Mrs Dallas is a very natural, lively & nice looking person, just 22…but the Indian type is remarkably plain, considering she is two generations removed from it…Even her intonation & voice are characteristic (as we now perceive) of her descent…

Tuesday, February 26. At two o’clock, the Bishop came to take us to the Collegiate Schools. We went first to that for girls—and found them assembled 25 in number—others being absent on account of the recent bad weather which prevented them from getting over from Esquimalt. These were the young ladies of the colony—those requiring the best education, including music, singing, drawing, French, Italian, German & Spanish. They were apparently of all ages between 8 and 18, and several were coloured…

The Bishop had conveyed to my Aunt an invitation to take luncheon the next day with Mr & Mrs Harris, a very rich butcher, who is also contractor to supply the Navy here with meat. They are excellent people…but are not blessed with over much education, more’s the pity!…

This afternoon my Aunt received from our landlord, a paper on which were the names of some 20 of his coloured brethren, all in most respectable positions here, who wished to be allowed to pay their respects to her. The Bishop is particularly pleased at this, and has asked if he may be present when they come.

Wednesday, Feb. 27. The Bishop came to take us to our luncheon at Mr Harris’s. He has one of the best houses here, a substantial building of brick, some distance from the shop. They are plain, worthy people, without any pretension. He is making a great deal of money, is living in as much comfort as can be obtained in the colony, educating his children as well as he can, buying property and improving it extensively—and is therefore a public benefactor…Mr. Harris is just the sort of man to meet half way in his upward career…We liked our visit very much—everything was in good taste without affectation of any kind.

After luncheon, Mr Hankin [British Naval officer serving as an escort to the two women] managed to find a sort of American gig in which my Aunt could go to the native school, I walking with the Bishop. The building is circular (or octagonal) of wood lighted form the roof—standing upon a hill overlooking the harbour, and close to the Indian reserve on which all the Indians live…we found the school at work. They were in 2 divisions seated on benches…in separate tribes, the 2 larger divisions being occupied by the Hydah [Haida] & the Sang soo [Songhees] tribes, who are hostile to each other. Stray children of other tribes were on the small benches, the upper ones of which have a desk before them for writing.

They were all decently dressed, & many of the girls were wrapped in gay plaid shawls given them for good conduct; some, both boys and girls, were huddled up in the usual fashion in a dirty blanket, others wore a gay kind of wrapper made by themselves in red & blue cloth ornamented with rows of mother of pearl buttons, with pretty effect. We often see them on the streets here. Some wore rings of silver in their lips, ears & noses; and most of the bigger girls had bracelets of silver. One had 6 or 8 on one arm. They were much cleaner than we had any idea of expecting—even their lanky hair had evidently been combed, thought it was somewhat of a fuzzy crop and hung over their foreheads…

The school has been but a very few months at work yet already the children have learned to read small words in English & some of them write with wonderful neatness.

"

Bishop Hills wrote his own account of the school visit.

"Went with her to the Indian School, which…was assembled. The children sang Xtian Hymns. Classes were examined on reading. The copy books were inspected. Edenshaw the great Hyda Chief was present & sold a couple of silver bracelets beautifully graven. The Indians are proud of their work. Some presents were distributed—scissors & balls…We visited also several Lodges & saw 2 Indian babies with the pressure bandage on their foreheads. I remonstrated & the Indian woman declared she considered the straightness…“not good”—in answer to my declaration that the flattened forehead was “not good.” So she adheres resolutely to the fashion of the Flatheads.72

"

Sophia Cracroft continues with her description of her aunt’s visits with citizens of Victoria.

"Thursday Feb 28. We were engaged today to take luncheon with the Governor’s wife Mrs Douglas…Have I explained that her mother was an Indian woman, & that she keeps very much (far too much) in the background; indeed it is only lately that she has been persuaded to see visitors, partly because she speaks English with some difficulty; the usual language being either Indian, or Canadian French wh is a corrupt dialect. At the appointed time [the Douglases’ daughter] Mrs Dallas came to introduce a younger sister Agnes, who was to take us to their house. She is a very fine girl, with far less of the Indian complexion & features than Mrs Dallas…

The Governor’s house is one of the oldest in the place…it is 12 years old—standing in a large old fashioned garden with borders of flower enclosing squares of fruit trees & vegetable too I think. The house is a substantial plain building, with very fair sized comfortable rooms. Mrs Douglas is not at all bad looking, with hardly as much of the Indian type in her face, as Mrs Dallas, & she looks young to have a daughter so old as Mrs Helmkin [Helmcken] the oldest, who is 26. Her figure is wholly without shape, as is already Mrs Helmkin we hear, & even Mrs Dallas…

At 5 o’clock the Bishop came to be present at the visits of the coloured people who had asked my Aunt to see them, that being the appointed hour. The first was Mr [Mifflin] Gibbs, a most respectable merchant who is rising fast. His manner is exceedingly good, & his way of speaking quite refined. He is not quite black, but his hair is I believe short & crisp. Three other men arrived after him & he took his leave soon after, having acted rather as spokesman for the others, who then explained that they were the Captain & other officers of a Coloured Rifle Corps, & the Captain proceeded to speak very feelingly of the prejudices existing here even, against their colour. He said they knew it was because of the strong American element which entered into the community which however they hoped one day to see outpowered by the English one;—that they had come here hoping to find the true freedom which could be enjoyed only under English privileges, & great had been their disappointment to find that their origin was against them. My Aunt sympathized with them of course & said she knew that their claims had been always maintained by the Bishop as representing the Church. This observation was eagerly taken up by the Lieut who said but for the stand made on their behalf by the Bishop & his clergy, the coloured population would have left the colony in a body. We shd thus have lost a most orderly and useful and loyal section of the community. They naturally detest America & this Rifle corps has the San Juan claim, still pending. As he went out, the Captain said “Depend on it Madam, if Uncle Sam goes too far, we shall be able to give a good account of ourselves.” You can imagine how gratified the Bishop was by this emphatic declaration of their obligations to himself & his clergy.

This party was followed by a Mr and Miss Lester (his daughter). He is the partner of Mr Gibbs—certainly one or 2 degrees from the pure negro & his daughter is as fair as I am, with nice ladylike manners & appearance. With these, the conversation was more general, and after they were gone the Bishop told us that Miss Lester was actually expelled from a school in San Francisco where she was carrying off prizes, because her nails exhibited a dark shadow which is said to be the very last discernible trace of negro blood! She is very well educated, and her younger sister is in Mrs Woods school, probably as fair as any of her companions.

I need not tell you that all these people expressed their feeling of pleasure at seeing my Aunt, and they certainly do speak with a propriety & a degree of refinement which is peculiar to their race & certainly superior to the same rank among Englishmen…All of them who called are church people, attending constantly, and he [Hills] knew them all.

"

Bishops Hills also described this visit.

"I was present with Lady Franklin when she received a deputation of Coloured people. They surprised her by their intelligence & good manners—equal if not superior to any of their positions in society—the sons of tradesmen. They told her they had much to suffer from the prejudice & that had it not been for the stand made by the Ch of England they would all have gone away from the Colony.73

"

Lady Franklin and Sophia Cracroft commented on the shops in Victoria and took part in quite a social whirl.

"Friday March 1. We managed to get in some shopping today & were surprised to find things so good & plentiful…We were surprised at the excellence of the restaurants, conducted after the French fashion & refuge of the numerous bachelors…

This evening we were to dine at the Colonial Secretary’s…You would be amused to see us trudge on foot to dinner parties…As we walked, we heard shouting & singing at a distance, & learned that it came from a party of Indians from the north, who had arrived in canoes during the day…We got home all the safer for the Bishop’s lantern he coming round by our house to give us the benefit of it…The perfect quiet and order of Victoria at night is surprising—there is not the smallest approach of any annoyance…

Saturday March 2. We also visited the Hudson Bay Company Store. They import direct from England everything you can think of in the way of dress, as well as groceries and other stores, of course at a very great advance on their original cost.

At another place we saw some of the Fraser river gold, in dust, in scales, in nuggets, 7 in lumps made of dust amalgamated by quicksilver…

Sunday March 3. Mr and Mrs Dallas & Mr Mayne [Royal Navy officer] came to take us to Christchurch. We sat in the Governor’s pew—a large square one under the organ gallery…The congregation was a very good one, and we were struck by the large proportion of coloured people. You must remember that they are never [italics in original] seen in America, but have churches all to themselves…Mr [Edward] Cridge [the cleric] read the prayers…

Monday, March 4. At 2 o’clock the Bishop came to take us to the Boys’ Collegiate School…We found between 40 and 50…they a very nice looking set of boys—in rank, from the Governor’s son, downwards. They were not more than 2 or 3 coloured boys & even those are not very dark. One however is a fugitive slave…On leaving, they cheered my aunt uproariously…& told her they had just unanimously declared that they would name their Cricket Club after her!…

Tuesday, March 5. We started at 7 to go on board the “Otter” belonging to the Hudson’s Bay Company, which goes weekly to New Westminster. Mr. Dallas came to take us on board & introduce us to the Captain (Mowatt) who kindly gave us the use of his cabin, on deck, where we passed the greater part of the day…We passed close under the disputed Island of San Juan & it was rather tantalizing not to be able to land…

We had a beautiful view of the mountains as we crossed the Georgian Gulf & entered the Fraser river between low banks covered with tawny reeds, which looked like tracts of cornland ready for the harvest. Our fellow passengers were pretty numerous, chiefly miners & of many races. French, German & Spanish were spoken, to say nothing of unmitigated “Yankee.”…There was also a party of theatrical ladies & gentlemen—one of the former, very pretty.

"

The two women spent the night with Colonel Moody and his family at the Royal Engineers camp near New Westminster. The next morning before they embarked on a trip up the Fraser River, they “walked about the Camp, admiring the taste & order which reigns throughout it.”

"Wednesday, March 6. The Engineers are 120 in number, all volunteers, come out for 6 years, at the end of which period they may either remain in the service & return home, or be discharged & receive a grant of 30 acres. Meanwhile they receive additional pay & are already buying bits of land. Thus a most useful class of colonists is being created, for in the Engineer corps every man is taught a trade…

We embarked on the “Maria”…Gold is found almost everywhere along the banks of the Fraser above New Westminster…miners have been continually penetrating farther & farther into the heart of the country…Yale is the farthest point of steamboat navigation…The intervening settlements are at Langley, Old and New, about a mile apart, and Hope…

Miners have been constantly penetrating farther & farther into the heart of the country. These are the most adventurous & hardy, & the ground they have abandoned is now being worked chiefly by the Chinese who have come over in thousands, live mostly upon rice, and are content with a small return for hard work…

We had a good many passengers, including 2 Chinamen miners—the better class slept in the [italics in original] cabin, the dining tables being shoved aside, & mattresses put all over the floor. The upper end of the cabin had 3 sleeping cabins on each side with 2 berths in each, but the manager kindly ordered that I should have a cabin all to myself Buckland [Lady Franklin’s maid] being in another…The narrowed part of the main cabin between these for sleeping formed a kind of after cabin in which was a small table which was treated as our [italics in original] property—here my Aunt & I breakfasted whenever we pleased, & had our tea also…

Thursday, March 7. We untied ourselves & started again by daylight…A little beyond one of the villages was a burying place, consisting of rows of large boxes or chests raised from the ground, and ornamented with figures carved in relief…

We passed a few miners only—all Chinamen, on the edge of the river, rocking their cradle so constantly & intently, that they seldom even raised their heads as we passed. They keep to their own costume & look as quaint as they do in pictures, with their round, pointed hats. Behind them was either a cotton tent, or a little wooden hut sufficient for the 2 of them. They were rarely more.

Friday, March 8. We were fortunate in finding here [at Yale] one of their winter habitations, which again reminded me of the pictures in my child’s book of this part of the world. It consists of a great hole, or excavation, or rather burrowing sufficiently large to hold many people. I believe several families occupy one, as they do a single lodge. Over the top a great mound of earth is raised, and trodden into a compact roof in the centre of which is a hole which alone affords light & air, and the means of getting in and out by a ladder made of a notched trunk of a tree. We looked down this hole into the “sweating house” as it is called—now empty—but Mr Crickmer [Anglican cleric at Yale] came down into it some little time ago when it was fully occupied by its usual winter population. He says the heat was something awful!

Monday, March 11. [Returned to the Moodys’ house.] The main point at issue here is the union of the vast territory of British Columbia, with the vastly smaller one contained within Vancouver Island. The fact that B. Columbia is governed by a Chief residing in Vancouver Isd is a pill too bitter for the pride of a British Columbian! It irritates them even to reason upon the point; and they argue that the Governor ought to pass half his time with them [italics in original] & spend half his salary for their benefit…

All people speak with great admiration of the Governor’s intellect—and a remarkable man he must be to be thus fit to govern a colony…He has read enormously we are told & is in fact a self educated man, to a point very seldom attained. His manner is singular, and you see in it the traces of long residence in an unsettled country, where the white men are rare & the Indians many. There is gravity, & a something besides which some might & do mistake for pomposity, but which is the result of long service in the H.B.Cos service under the above circumstances…

"

Back in Victoria the women “went over the bridge, to an iron foundry & near the Indian village.”

"Thursday, March 22. We walked home through a street hitherto unknown to us, chiefly the resort of the Indians (who however are seen everywhere throughout the towns—in the morning carrying cut wood for sale; the women, baskets of oysters, & clams)—with shops kept mostly by foreigners, fish being generally sold by Italians. We stopped at one & my Aunt said a few words to him in Italian which enchanted him I could see. There were many Germans & plenty of Chinese—“Wo Sang—washing & Ironing done here”—“Gee Wo—washing”—I only remember these two names at this moment—the Chinese wash & iron particularly well. They are very industrious & well behaved.

There are also many Jews in the Community—most of them from Central Europe.

Sunday, March 24. [Left for San Francisco.] Altogether this visit to Vancouver Isd & British Columbia has been a very pleasant, as well as a deeply interesting one, and we trust to see the colonies encrease in prosperity—the foundation of which must be laid in emigration from England, or at least from English colonies, so as to absorb (or at least outweigh) the American element…

It is the ladies who are most to be pitied as they must absolutely & unreservedly devote themselves to the smallest cares of every day life—at any rate they must expect [italics in original] to have their hands so filled day by day & be prepared for the worst. But there is a set off to this in the fact that all are in the same predicament & there is not the least pretense to anything better. There is not a single lady in the colony who has a nurse, a cook, & a housemaid, so she has to be one of these, if not all three—this state of things saps mere conventionality at the very root—strong friendships are formed, and people are ready to help one another. There is something very interesting too, in watching the growth of a young colony which is making rapid strides as this does, especially when a good standard of civilization & morals have existed from the very first. Nothing could have produced this but the constituting it into a distinct See with a resident Bishop, whose vocation is a standing witness against the sordid tendencies of a gold producing colony.

As a community, the people of Vancouver’s Island seem a very contented one—enterprising, yet without the grasping of Americans who are never satisfied unless they find themselves preeminent, if not alone in the field; and the wonderful growth of the colony during its 2 years only of existence, is highly to the credit of its people.74

"

Back to the everyday life of Bishop Hills

The departure of Lady Franklin and her niece Sophia Cracroft in late March 1861 returned Bishop Hills to the everyday, whose successes and failures he interspersed, as was his wont, with new adventures and understandings.

A week later Hills garnered a small victory respecting the admission into the girls’ school of a student whose mother had “a strong prejudice against Colour,” but who then “gave way & confessed she had managed her scruples & would now place her child & keep her there until she was full educated.”75

In early April Hills visited “an earnest & intelligent…coloured family” in New Westminster he had known almost since his arrival, who lived opposite the school of the Catholic Sisters of St. Ann, which their daughter attended, informed how when “the Americans & others (English) objected to the mixture of Coloured & others (English),” the Catholic bishop had obligingly ordered their separation, whereupon “the Coloured children were then all withdrawn.”76 It was, and continued to be, one step forward, one step back.

Another yearly round in British Columbia

In May 1861 Bishop Hills began his third yearly round in British Columbia. Leaving Victoria on the evening of Tuesday, May 28, he along with three other Anglican clerics arrived in New Westminster the next morning and visited locally before boarding a vessel that “reached Douglas about 6 o’clock & encamped in an unoccupied corner of the Garden of the” local Anglican cleric.77

The local Lillooet people were first off the mark to host the arrivals. “After breakfast an old chief & his friends came to see me” and made arrangements for a visit:

"At the Quay a handsome Canoe was waiting to take us to the Village. The crew consisted of two bright eyed & smartly dressed young ladies & two others of the same sex. We were escorted upon landing at the Village by a numerous party & soon entered a large house capable of containing 800 people. This was the mansion of Jim Douglas, the principal Chief. About a hundred Indians were present. They laid mats. We took our places & all the rest sat down. I commenced by telling them who I was and what I had to deliver to them.

"

Over the course of the day spent in Douglas, Hills “went round & called upon most of the people” including “Italians, Germans, Norwegians, French, Africans,” and “Americans, Scotch, English & Irish—Canadians were also seen.” Later, when donations were entertained, “among contributors to Douglas Church were Americans, Germans, Norwegians, Africans.” In the evening a “White Man’s Service” was held, to use Hills’s term, which “the Indians” requested and received permission also to attend. “They filled up the many parts of the room & stood around the door outside & listened at the windows.”78

Come Sunday, June 2, at Douglas, Hills held three separate religious services. At 11 a.m. “people of various nations were present.”

"At 3 pm we went to the House of the Indian Chief “Jim Douglas.” Above 160 were present. Mats were placed for us to stand & sit on. The chief stood up in the midst of his people & directed their movements. We instructed them in simple truths. They were dressed in their best. After we had finished a party belonging to another chief desired instruction at his house & thither Mr Garrett went. [That evening] we again had service in the Town…We had fewer than in the morning…Indians were present in the morning & Evening who hung about the doors & crowded at the windows.79

"

Monday, June 3, Hills and the others were on the road again, rising “at ½ past 3” and setting off after breakfast to the 4 Mile House, 10 Mile House, where “a Swiss named Perry entertained,” and “reached the 20 mile House—the Host at ½ past 2 having walked the distance including stoppages in 8 hours…In the Evening until dark Indians surrounded our tent & eagerly received our Instruction. I explained elementary Xtian Truths.”80 The next day they travelled by pack train and boat to Pemberton, but the following day was a disappointment: “Rose at 4, it rained. We waited till 11 before we started & then off in the rain. The road is bad, a mere mountain track.”81

The days as narrated in Hills’s journal had a certain similarity, the Anglican clerics trudging from place to place—Anderson Lake, Seton Lake, Cayuse, Lillooet, Lytton, Boston Bar, Spuzzum, Yale, Hope—with evening services sometimes poorly attended. “I preached…there were 10 persons besides ourselves. One of them was a Mexican”—with hopeful references in Hills’s account to numbers of attendees or distinctiveness, as with the lone Mexican on June 6.82

Wherever Hills went he sought to preach both to whites and to Indigenous people, sometimes together, more often separately. For Indigenous people, having the bishop preach to them in their own building was a special event, as happened at Yale on the last Sunday of June 1861, during which Indigenous people seemed to believe they were genuinely interacting with whites on their own terms. And perhaps they were, at least in the moment, so Hills recounted in his journal:

"At three o’clock the Indians were assembled in the Chief’s House to the number of about a hundred. They were called together by themselves by the ringing of a bell. The sight was highly picturesque. All were dressed in their best, some in good suits of black cloth, with silk neckcloths, white shirts & rings. Others had got cloth trousers with a scarlet or other bright coloured shirt a la Garibaldi with a crimson scarf. The ladies were in all stages of attire from the more humble & simple dress to the latest fashion. The hair went from the most dismal dishevelment to the neatest plait. All wore clothes in articles of foreign manufacture shewing they had completely left their native modes & that they were good customers to the shops.

Mats were laid before us—and new ones on a raised seat for us…At the close of each of our addresses all uttered a loud cry of approval and we were occasionally interrupted by some one calling out—good talk—good talk & pointing reverently upwards towards Heaven.83

"

Hills’s perceptions of the state of affairs

Four days later, on July 4, 1861, as “American Guns were fired” at twelve noon to honour the United States’ Declaration of Independence, signed on that day in 1776, Hills took note in his journal how “now the Flag did not wave so haughtily, since no longer are the States United.” The American Civil War was in play; slave-owning southern states had broken away from the eighty-five-year-old union, putting its future into question. “In firing the guns at 12 the attempt was made to raise a cheer but no hearts or voices were in turn.”84

A week later, amidst his daily entries, Hills ruminated on race, this time less hopefully than earlier. Drawing on what a local Hills considered credible had shared with him, the information found its way into his journal without editorial comment:

"The half breeds he said do not turn out well. When brought up in good company they do. Otherwise they drink & are dissolute. The cause of their failure thus far is that men from Canada, not the best but worst, came amongst the Indians. Only the scum of the women wd consent to receive them. So the alliance on both sides was low.

The better Indian woman would not allow a white man to catch them. In some tribes rather than such should happen a woman would destroy her own life.85

"

It was almost inevitable that race won out in his journal entries, especially when it was joined in Hills’s mind with an uneasy attitude toward what he perceived, perhaps despite himself, as unacceptable female behaviour.

Following stops in the Fraser Valley, Hills returned to Victoria on August 3, 1861, a little over two months after starting out on his summer road trip.

Another mighty adventure

Bishop Hills’s pursuit of souls across much of today’s British Columbia almost inevitably lured him to the Cariboo gold rush. Heading there from Victoria on June 16, 1862, Hills and two others took the sternwheeler Enterprise to New Westminster along with “10 horses six of whom were heavily laden,” and in the company of “a good number just arrived from N. Zealand & Australia” to try their luck in the Cariboo rush. The contingent boarded a “River boat with 84 Passengers & 40 Horses” with an overnight stop at Hope to stay with the local Anglican cleric, doing much the same at Yale. There Hills preached on Sunday morning “at the House of Tom the Indian Chief, where about 98 Indians were assembled,” and later in the day for whites “hardly supplying a dozen,” which he attributed to the population consisting “almost entirely of Jews & Americans.”86

Aware that smallpox had “made its appearance,” Hills and the others came prepared and while at Yale vaccinated “about 30 or 40 of the Spuzzum tribe” and later others as requested. Hills described the process:

"The scene was very striking as Indians of all ages were grouped around with one arm bare waiting for their turn. I showed them the mark on my arm & told them it was done when I was an infant…The readiness with which these tribes trust us & yield to our advice is a great proof of their confidence in us of the opening for higher and better objects than care of the body.87

"

Next came a stop at Lytton, where to Hills’s and the others’ disappointment they only “met 3 or 4 British subjects, the rest of the people are French, American & Mexican.” Hills had brought with him “a plan for a Church at Lytton but…found no encouragement to propose it.” Stopping at a nearby farm, he was all the same impressed by barley being cut for hay, and potatoes “looking well” as did turnips and beets. They once again camped before Hills and one other headed to Lillooet, where they had the advantage of new road construction.88 “The change is like magic,” Hills observed in his journal on July 3.89

Hills and the others pushed on, holding religious services at road camps on Sundays, admiring working farms from time to time, and reaching Williams Lake on July 14, 1862, Alexandria a few days later. Hills now considered himself “in the Cariboo country,” so he penned in his journal. His entries would be awash over the next two months, to mid-September, with the requisite gold miner stories, interspersed with weekly religious services so far as feasible. Among the bits of information Hills jotted down in his journal was, after a discussion with a “Frenchman…long away from France,” how a “miner can live for 3 or 4$ a day, giving himself three meals a day, with flour, beans, bacon, sugar, tea, coffee, dry apples xc.”90

Sunday, September 7, Hills held two services at Williams Lake with “not a dozen present at either.”91 Leaving Dog Creek on September 10, Hills and the others were joined by various persons along the way. Reaching Yale on September 22, Hills learned from the recently appointed Anglican cleric, Henry Reeve, how “a subscription has been commenced for a Church,” with contributors including twenty names, likely local merchants, in a community where, Reeve told Hills, “there were about 200 residents,” of whom “but 5 are Englishmen.” As for the evening’s congregation, “there were present 2 Jews, 1 Romanist [Catholic], 2 Methodists, 1 Cantonese,” and “one a professing member of the Ch of England.” Not unexpectedly, Henry Reeve looked “to the Chinese & Indians with more encouragement than that of the white population…Such is our work,” Hills editorialized at the end of his journal entry.92 The Anglican Church was in effect doing double duty, not only attending to parishioners, but also looking after the community.

Yet another adventure

Less than a month after returning to Victoria at the end of September 1862, Hills was off again. Almost as soon as the Grappler left Victoria on October 27, fog caused it to anchor. Given “there was a goodly gathering of the ships’ company & settlers on board & the awning was lighted by lanterns,” Hills, never one to pass over an opportunity to do so, preached.

Two days later at Comox, which Hills described as a “very active & bona fide settlement” with substantial log and lumber houses, and rich soil, he “went on shore to visit settlers.” There he “found Mr. Pidcock son of a Clergyman in England,” who had brought letters of introduction when he arrived in British Columbia and was now keeping a store. Hills noted how “there were about 37 or 40 settlers, amongst them but two women.”93

When Hills returned to preach in Comox three years later in November 1865, he would count “about 70 white inhabitants” with “six white families.” Hills was not best pleased by some of their behaviour:

"I visited a Settlers House close by—(Mitchell) who lives with an Indian wife…Many settlers live with Indian women. Such is the fall of a young man (named Pidcock) son of a Clergyman in England & himself once a Communicant. As the Indians passed his hut they shouted in a way showing they had but little respect for him.

Another case is that of (Muster) the son of an English Clergyman who lives unmarried with a person who was a servant in the family & has two children. He has an allowance & refuses to marry her because he says his allowance [almost certainly from his family in England] would be withdrawn if he did. He drinks and ill uses her. She has once or twice gone to live with another & even now while living with Muster contemplated being married to a man expected shortly from Cariboo. Can anything be more melancholy than such a state of things! Then the poor Indians are close lookers on upon all this depravity in the white race…

I visited the house of a man (named Wilson) who once lived with Indians in the way above stated he has under better influence given up his sin heartily ashamed.94

"

The gender disparity, according to Cowichan historian Eric Duncan, may have arisen because sixty some single Englishmen, including Reginald Pidcock, who had previously been a clerk in London, arrived there in 1862. They accomplished much, including building the first sawmill.95 But Hills had by now almost certainly garnered another insight, becoming aware that, given almost all newcomers were men on their own, and white women were in short supply if accessible at all, even some men respectable by his lights had partnered, or would partner, with Indigenous women.

The 1862 trip continued with stops at Nanaimo and then the Cowichan where “several young English Gentlemen offered to do all they could to help” so as “to have everything English & reproduce English religion & civilization.” Hills “observed that Settlers when they first come out are more anxious about such higher advances than they are afterwards,” hence “we shd take hold of this good feeling while it is warm.”96 Hills returned to Victoria on November 6 from his eleven-week mighty adventure.

Victoria’s conflicted sense of self

Four days later, on November 10, Hills attended what he termed “a fitting observation of the coming of age of the Prince of Wales.” Born in 1841, Queen Victoria’s eldest son, Edward, known as Bertie, would remain her heir for almost four decades until his mother’s death in 1901. The celebratory dinner to which Hills was invited was chaired, he described in his journal, by “Major Thomas Harris a patriotic Englishman who by industry as a Butcher & Contractor has attained the honorable position of first Mayor of the City of Victoria.” This was the man Lady Franklin had visited in 1861, who Sophia Cracroft had described as “plain, worthy people, without any pretension.” At the table, Hills noted proudly, “the Governor [was] on his right hand & myself on the left.” Other dignitaries including Captain G.H. Richards, head of the British survey of Vancouver Island then underway, and the “R. Cath. Bishop” were accorded lesser positions at the dinner table.97

All well and good, but not quite.

Continuing with his description of the celebratory event, Hills wrote in his journal, “The most intense Patriotism seemed to prevail, I was struck also by the strong southern sentiment.”

"There were French & American residents present the latter from the South. The Band amongst other tunes played “Dixie land” which carried the people beyond all bounds, they stamped—shouted & encored. The Mayor & Capt. Richards the senior naval officer were anxious to stop it, lest it should seem a demonstration of British authorities upon the question. They would not be stopped, nor would the band obey orders, but Dinner went on. The Governor made an admirable speech.98

"

It turned out, Hills described in his journal, that an event earlier in the day backgrounded the evening’s proceedings:

"In the morning a Secession Flag had been hoisted in the Town, upon which the American Consul hauled his down & was followed by all the N. American Inhabitants who took no part in the proceedings of the day. Towards the afternoon the Consul thought better of it & raised his Flag again, but not before he had written to the Governor a letter to say why he & others of his nation took no part in the proceedings. This circumstance, a sad mistake on the part of the American, may have added intensity to the feeling of the Evening.

The tone of the company was rough & unruly, at the end one individual insisted upon returning thanks to the Municipal Council. The Mayor had already done so. Being also somewhat inebriated & threatening to say something, a body of either his friends or his foes or both forcibly carried him out of the room. His Excellency [Douglas] previous to this had retired from the disorder.99

"

Hills was not sure what to make of the evening’s events, recording in his journal how “on the whole I think good will have come from this demonstration of loyalty.”100

The middle way

Hills continued his daily and seasonal rounds in much the same fashion until his return to England in the spring of 1863 to raise funds to sustain his work in British Columbia. While there, Hills married a vice-admiral’s daughter, with whom he returned to British Columbia at the beginning of 1865. Four years after her death in 1888, Hills resigned as bishop of British Columbia and again returned to England, where he died three years later in 1895.101

In those critical years of the early 1860s in present day British Columbia, Bishop Hills provided a middle way between the top-down approach of the governor and the Colonial Office concerned with income and expenses, roads and settlements—and the occasionally racist and sexist views of white settlers and gold miners who did not see Black, Chinese, and Indigenous peoples, including Indigenous women, as human beings like themselves. Although Hills came with his own assumptions and biases, he for the most part tolerated and accepted everyone—though maybe not Roman Catholics—welcoming them to his church and enjoying their company, setting an example for others.

1 “The Journal of George Hills,” 1860 to 1895, the year of his death, typescript in Ecclesiastical Province of British Columbia, Archives, which generously made a copy of the typescript available to me. See also Roberta L. Bagshaw, No Better Land: The 1860 Diaries of the Anglican Colonial Bishop George Hills (Victoria, BC: Sono Nis Press, 1996), 11–12, 19–20. For the 1860 diary in its entirety, 47–382, I have preferred the typescript.

2 Jean Friesen, “George Hills,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hills_george_12E.html.