10. World War II

The assertion is often made that Canada came of age as a nation during the Great War of 1914–1918, but it was World War II that profoundly transformed the country. On September 3, 1939, Britain and France declared war on Germany after Hitler had ordered German troops into Poland two days earlier. Canada issued its own declaration of war a week later, plunging the country into a six-year conflict that traversed the globe, claiming tens of millions of lives. As in World War I, British Columbia had the highest enlistment rate in the country.

While Canadians fought for democracy in Europe, workers left behind fought to make sure that democracy at home included union rights. The time was ripe. Governments saw the need to avoid the class turmoil sparked by World War I and end their standoffish approach of the Depression. They were open to reform. Labour’s decades-long demand for federal unemployment insurance was realized in 1940. Universal family allowances were introduced in 1944. And at long last, after seventy years of struggle, the fight for compulsory recognition of unions and collective bargaining was finally won, first in British Columbia and then across Canada.

In 1943, amendments to BC’s flawed Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act gave the government authority to recognize a union and force employers to bargain. They were the most advanced in Canada, giving BC workers virtually the same organizing rights US workers had had since the 1935 Wagner Act. Bogus company unions and the use of police-protected strikebreakers to thwart a union fighting simply for the right to be recognized at the bargaining table were now anomalies. The amendments were brought in by the province’s first coalition government, an uneasy alliance between the Liberals and Conservatives put together when neither party won a majority in 1941. (The CCF, which topped the popular vote, remained on the outside.) The amendments were promoted by the coalition’s reformist labour minister George Pearson, a sixty-one-year-old wholesale grocer from Nanaimo and a carry-over from the administration of Duff Pattullo. Although imbued with the anti-Asian racism of the day, Pearson was a rare friend of labour among his cabinet minister peers.

A grander breakthrough came early in 1944, when the federal government further enshrined union rights with its landmark order-in-council bearing the banal title of PC 1003. As in BC, the federal measures introduced under the War Measures Act gave unions legal bargaining rights for the first time, forcing companies to recognize and bargain with unions chosen by a majority of their workers. PC 1003 applied to all Canadian workplaces under federal jurisdiction, which had been extended early in the war to every major industry in the country. It gave certainty to BC’s amendments, and other provinces had no option but to comply.

Since PC 1003 also removed the right to strike during a collective agreement, some have referred to the sweeping changes as a historic compromise. But for unions, it was a compromise to be welcomed. For generations, they had seen governments either stand by or actively participate as employer after employer stymied their aspirations. Thanks to the war, the ground had shifted. Governments assumed a new neutral role, at least on paper, still trying to settle disputes through compulsory conciliation, but otherwise letting union organizing and legal strikes take their course. It was a fundamental change. Meanwhile, the federal government’s obsession with balancing the budget, which had shortchanged millions of suffering Canadians throughout the 1930s, had suddenly disappeared with the first shot in Europe. By the fiscal year 1943–1944, federal spending skyrocketed to $5.3 billion, eight times what it was a mere four years earlier when the war began.

BC was in the thick of the booming wartime economy. From fewer than a thousand employees in 1939, Vancouver and Victoria shipyards grew to more than thirty-one thousand workers, turning out hundreds of merchant ships and naval vessels at breakneck speed. Burrard Dry Dock in North Vancouver became the busiest shipyard in the country. There, it was said, one could walk half a kilometre on ships under construction without touching the ground. Ferries carrying workers to and from their shifts across Burrard Inlet were often so crowded that passengers had to hang off the outsides of the vessels.

Boeing established aircraft plants in Vancouver and built a major factory on Sea Island in Richmond that produced “flying boats” for Canadian and US air forces, and later, sections of B-29 bombers. Mines, sawmills, logging operations, pulp and paper plants and the huge smelter at Trail maintained a feverish pace to meet the insatiable demands of war. Agriculture expanded too. And in the north, the building of the historic Alaska Highway opened up the Peace River region. By 1943, all this activity gave British Columbians the highest per-capita income in Canada.

On the union front it was full bore ahead. Bolstered by compulsory union recognition at last and the need for large, stable, industrial workforces to spur production during the war, union organizing took off. No longer could employers turn their backs on workers demanding improved wages and working conditions. For the first time, governments accepted that unions were vital partners in the economy, their yearnings legitimate. The craft union dominance of the labour movement also began to wane, challenged by the rising clout of industrial workers and their unions.

Three months after the declaration of war, the country had a new national labour organization. The Canadian Congress of Labour resulted from a merger of the CIO’s expanding Canadian affiliates and the weakening All-Canadian Congress of Labour (ACCL), which had been founded in 1927 as a rival to the craft-led Trades and Labor Congress of Canada. Privately, ACCL president Aaron Mosher and Charles Millard of the Ontario Steelworkers, with CCF national secretary David Lewis prominent in the background, were anxious to curb the influence of industrial unions headed by members of the Communist Party. But for the moment, all factions united around the goal of organizing the unorganized under the CIO’s philosophy of one union in each industry.

The Communist Party of Canada was banned early on under the War Measures Act. Prominent CP members were even interned for a time because of their initial opposition to the war. That changed the moment German tanks poured across the Soviet border in June 1941. After that, no one was more eager for the conflict than the suddenly pro-war communists, to the extent of adopting a no-strike policy and urging support for the Mackenzie King government in Ottawa. They were allowed to regroup in 1943 as the Labour Progressive Party (LPP).

In BC, far less fearful of being fired and blacklisted for joining a union, waves of workers took out union cards. Local 1 of the Boilermakers and Iron Shipbuilders’ Union of Canada led the charge. Representing more than fourteen thousand Vancouver and North Vancouver shipyard workers, Local 1 became the largest union local in the country. “During the war, governments were forced to seek labour’s goodwill with favourable labour legislation,” recounted Bill White, the Boilermakers’ tough president at the time, in his colourful memoir A Hard Man to Beat. “Many companies, with cost-plus contracts, found it cheaper to give in rather than lose production with a strike. We made big gains.”

Besides across-the-board wage increases, those big gains in the shipyards included extra pay or “dirty money” for working in cramped, fume-filled quarters (won after a series of sit-down strikes), the first holiday pay for BC workers, longer rest periods, a good minimum wage, equal pay for women and a virtual union shop. On the job, the Boilermakers also pioneered a number of new labour practices, enforcing them with a very strong system of elected shop stewards. “When I look back, I realize I was seeing the formation of the modern labour movement,” said White.

At the same time, in a sign of the fierce ideological battles to come after the war, the union’s left-wing leadership had to fight off interference from the CCL’s anti-communist president Aaron Mosher. When a left-wing executive slate was elected by mail referendum in December 1942, Mosher voided the vote and put Boilermakers Local 1 under trusteeship. Turmoil swept the union. Backed by packed membership meetings, the deposed leadership and a three-hundred-strong shop stewards’ committee refused to surrender control. When Mosher reappointed former executive members who had been voted out, more than a hundred shop stewards blocked their entry to union offices in downtown Vancouver. The Boilermakers then upped the ante, winning membership approval to leave the CCL and holding new elections that returned ousted leaders to their posts.

The battle moved to the courts, where Supreme Court Justice Sidney W. Smith ruled that the CCL’s suspension of Boilermakers Local 1 was illegal. He ordered yet another round of elections to determine the membership’s wishes once and for all. Close to six thousand members amassed in Vancouver’s Athletic Park to elect a new executive. “All streets leading to the stadium were lined with parked cars,” The Daily Province reported. “The huge crowd crawled along the sidewalks from south, east and west for an hour, showing their cards at the gate before being admitted.” A shipyard pipe band added to the memorable occasion. When the ballots were counted, anti-Mosher candidates held every position on the union executive. After another Supreme Court decision went the local’s way, Mosher threw in the towel.

Elsewhere, union organizers spread throughout the province, signing up workers in industries that had long resisted unionization. The militant International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers’ (Mine Mill) launched a successful drive to organize the large workforce at the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company’s huge smelter in Trail in 1944. Labour minister George Pearson, who became friendly with Mine Mill’s larger-than-life communist leader Harvey Murphy, acknowledged its triumph at Trail as “one of the greatest accomplishments of BC unions in recent years.”

In addition to its success at Trail, Mine Mill organized thousands of Kootenays metal miners. In the Okanagan, the Fruit and Vegetable Workers established the province’s first agricultural-based union in 1943. Office workers and even newspaper reporters joined unions for the first time. The upsurge also swept over the Vancouver waterfront. After twice losing their union following grievous strikes in 1923 and 1935, the city’s resilient stevedores overthrew their company union once again. Four hundred waterfront workers voted unanimously at a special meeting toward the end of the war to join the CIO’s International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union. This union stuck.

The organizing outburst spurred new and rejuvenated Canadian Congress of Labour unions to join in common cause. The Vancouver Labour Council, set up as a rival to the craft unions’ Vancouver Trades and Labor Council, grew from a handful of unions to include thirty-eight affiliates with twenty-eight thousand members in just four years. Other new labour councils were set up in Victoria, Prince Rupert, the Okanagan and Nanaimo. But the biggest move came in 1944 when CCL affiliates revived the BC Federation of Labour. The original Fed had fallen apart in 1920 during the brief ascendancy of One Big Union. The founding convention of the second Federation of Labour took place on September 30 at the Boilermakers’ union hall on Pender Street in Vancouver, attracting seventy-three delegates from unions affiliated with the CCL.

CCL regional director Dan O’Brien, who pledged to steer an even course between the CCF and the communist LPP, was chosen as president. Radical left-wingers Harvey Murphy of Mine Mill and Harold Pritchett of the IWA were elected as vice-president and secretary-treasurer respectively. More than half the delegates were from the IWA, along with significant numbers from Mine Mill and the Boilermakers. Despite its leftward tilt, the convention generally avoided ideological matters and concentrated on the need to pressure government for better labour legislation. The born-again BC Federation of Labour quickly jumped into action.

On February 25, 1945, a mass delegation of 180 lobbyists from the Fed travelled to Victoria to pressure MLAs with a set of demands: compulsory deduction of union dues from pay cheques of unionized employees (known as dues check-off), rigorous safety standards, improvements to the Workmen’s Compensation Act, BC support for a national health insurance plan, a sweeping government housing program and nationalization of the BC Electric Company. Lobbyists were delegated to buttonhole individual MLAs on the ambitious platform and report back on their reaction. They stayed three days, receiving extensive media coverage and establishing high-profile labour delegations to Victoria as a regular ritual.

The changed circumstances in BC galvanized the International Woodworkers of America. Drained of resources, its membership down to a paltry few hundred and no contracts in place, the future of the IWA at the onset of World War II had appeared bleak. Now, with the desperate fight against fascism intensifying, workplace harmony was required as never before. The IWA had leverage. With workers unwilling to toil for the war effort in poor working conditions at sub-par wages while forest companies profited, organizing took off. The result was the greatest union organizing drive in BC history. By the end of 1946 the IWA was the third-largest union in Canada, with more than twenty-five thousand members.

The union’s campaign to organize the large Chemainus mill on Vancouver Island pointed the way to what was to come. Off and on since 1936, organizers had stood outside the gates to leaflet workers at quitting time. Half the leaflets were tossed on the ground, some spit on or thrown back. But in June of 1943, a three-week blitz reaped signed union cards from four hundred mill workers. Their certification as an IWA bargaining unit was a turning point for the province’s unorganized sawmills. “When [Chemainus] went over, she went with a bang,” recalled organizer George Grafton. “Everything [began to go] at the same time. You see, it was the war, the removal of fear from people’s minds, of losing their job.”

A similar pro-union mood prevailed among coastal loggers. This too was sweet reward for the many hardships endured by dedicated organizers over the years. Surviving on meagre income and grub, they had flitted into isolated camps in all kinds of weather, forever on the run from foremen and company stooges. In a typical incident, the camp superintendent at Elk River trailed two organizers on their bunkhouse rounds as they handed out copies of the BC Lumber Worker, snatching the paper away from each man. When they were through, he angrily handed back the entire bundle. Not a single logger protested. “They had no rights, and they accepted it,” said Grafton. These were gruelling times for IWA organizers. “The continual walking or rowing into the camps with the knowledge that the membership was dwindling everywhere else made it tough,” Myrtle Bergren observed in her engaging book on those difficult times, Tough Timber. “It was an arduous routine.”

It was during these years that the Loggers’ Navy was born. A way had to be found to visit the many logging camps scattered along ocean inlets, particularly on the Queen Charlotte Islands (now Haida Gwaii). The union scraped together some cash, bought an old but seaworthy cabin cruiser and learned to sail it. In no time, the Laur Wayne was known up and down the coast by loggers who looked forward to its visits as a welcome break from work. If a hard-nosed superintendent barred access to the camp, the crew blasted the vessel’s horn and the men gathered on the dock to hear the union gospel preached from the deck.

The key breakthrough took place on the lush, heavily forested Queen Charlotte Islands. In 1943, four logging companies had federal contracts to supply manufacturers with Sitka spruce for the famed high-speed Mosquito fighter-bomber, yet conditions for felling the tall timber were often abysmal. With the help of the Loggers’ Navy, the IWA had established a firm foothold in the camps. A federal conciliation board confirmed the IWA as the loggers’ accredited bargaining choice and recommended that the companies settle with the union. But the employers dug in their heels, vowing to never sign a contract with a communist-led IWA no matter what the board said.

Facing provincial legislation compelling companies to negotiate with certified unions, coastal forest operators feared an IWA victory would fling the gates wide open to organizing throughout the industry. They decided to draw a line in the log-strewn sand of the Queen Charlottes. Representing 75 percent of the industry, forty-two coastal forest companies threw their weight behind the Islands’ camp owners. They wired their support to the federal labour minister and took out large newspaper ads attacking the union. To dodge the labour legislation, they had adopted a strategy of agreeing to negotiate and even reach settlements with the union, but not put their names to an actual collective agreement. The tactic left the IWA with nearly ten thousand members throughout the province and only one signed contract. “We hate to have a knock-down, drag-out fight, but we cannot get anything at all,” complained IWA leader Nigel Morgan.

On the Queen Charlottes, the industry hoped to stall proceedings until the winter shutdown, or pressure the union into calling a strike, a move they were certain would bring down the wrath of government and the public for disrupting a key wartime industry. A strike would also be a quandary for the union, which had a no-strike policy as part of the LPP’s all-out support for the war effort. But after more than a year of company intransigence, the loggers were too restless to keep on the job. The union set a strike deadline of October 8, 1943.

The labour movement rallied to the IWA’s side. They took out their own newspaper ads. Endorsed by almost all major unions in BC, the ads lambasted the “so-called dollar patriots running the vital aeroplane spruce industry companies” for their refusal to sign an agreement with the IWA. By then the loggers were so fed up they jumped the deadline. On October 6, ninety woodworkers stormed out on a wildcat strike at Skedans Bay. Word flashed quickly to the other camps. Loggers’ Navy skipper John McCuish remembered: “As soon as [news] was received by delegates at a big camp, they went up to the engineer and said, ‘Blow the whistle, the camps are out on strike.’ So they blew the quittin’ whistle and that was it.”

In short order, more than five hundred loggers at eight camps were off the job. The strike was solid. No one left the camps. Supplies had been stocked up. Deer hunting and military exercises were organized “to keep the boys busy.” After two weeks, the operators ran up the white flag. Much to the industry’s surprise, public sentiment saw through their anti-communist ruse and backed the union. Reluctantly, the companies signed a one-year agreement providing a wage increase, progress toward an eight-hour day, seniority, grievance procedures, joint safety committees, travel rebates and union recognition.

R.V. Stuart, who co-ordinated bargaining for the forest companies, tried to put a positive spin on their surrender. The employers realized “the vital danger to the war effort was more important than their own private interest,” said Stuart, a realization that took nearly two years. The industry abandoned all resistance after that and fell in line. In early December, District Council No. 1 of the IWA signed its first coast-wide forest agreement, a one-year deal covering eight thousand employees in twenty-three camps and mills. Five years after the debacle at Blubber Bay, it was an extraordinary achievement. Not only was the great leap forward a victory over the forest companies, the contract was won against a backdrop of fierce internal battles with the IWA’s own international leaders in Portland.

The IWA triumph was not the only major advancement on the worker front during World War II. Women entered the industrial workforce for the first time. With so many men in the armed forces, their labour was critical. The influx was particularly dramatic in the shipyards. Beginning in late 1942, hundreds of women stormed the yards’ all-male ramparts. Jonnie Rankin was hired at Burrard Dry Dock. “It wasn’t like a women’s lib hiring. They needed our labour power, that’s all,” she recalled decades later. But the Boilermakers Union made sure women received fair pay for doing much the same job as men. Rankin was soon making more money than the average wage earner in the city of Vancouver, a Canadian equivalent to the USA’s ubiquitous “Rosie the Riveter.”

Rankin worked as a passer, fielding red-hot rivets tossed her way by using a slender cone with a handle, then using tongs to pass the rivets to a bucker for installation by a riveter. After a harrowing first day, when a smart-aleck youth purposely tossed the rivets close to her face, at one point burning off some skin, she mustered the courage to come back for a second day. “The next day I felt a little better, and all of a sudden I wasn’t afraid at all. The bucker showed me how to catch, how to move my bucket. I got so fast at it, and so good at it, that I was one of the first called when I walked into the yard. That was the highest egoism I ever had.”

Alice Kruzic was hired on as a sweeper for sixty cents an hour at the South Burrard shipyards. She embraced the chance to work, impressing male workers by rolling her own cigarettes. Kruzic, who kept her old shipyard overalls and cap for years, also appreciated being able to aid the war effort. “We were told we could go down to see [one of our ships] launched,” she recalled in the 1970s. “When I saw that ship slide down the ways, I was so proud. I felt that I had helped to build it. I wanted so much to win the war against the fascists.”

Of the huge workforce at BC Shipyards, 6 percent were women, the most of any shipbuilding operation in the country. In addition to rivet passers, they were plate makers, jitney drivers, painters and lathe operators. Some became welders and charge hands. Because of company concerns that they might mingle too much with the men, there were separate lunchrooms, lockers and gate entrances for women. Rankin relished it all. “I worked in the deep tanks and I was slimy. We’d get on those old street cars, filthy dirty. They wouldn’t let me sit down, so I’d hang off the back,” she said. “But I didn’t mind how dirty it was, or how rough it was. I just felt great.”

Union consciousness took hold among the women shipyard workers. Alice Kruzic and Jonnie Rankin both became strong union supporters. “The old Wobblies and those who had helped organize the union talked to me about their struggles,” said Rankin. “I got more of an education than you could get in three universities.” In June of 1943, a group of them staged a brief strike to protest the firing of a woman for altering her company-issued overalls. “We cannot let an act like this go unchallenged,” one striker told the Vancouver Sun.

Solidarity echoed elsewhere as well. Alice West helped organize a union at the Fraser River plywood plant where she was hired at sixteen. “My father believed in strong unions. It was something I breathed in quite early,” West reminisced many years later. “I still have friends from that plywood plant.”

Peggy Kennedy was hired by Boeing. She worked in the aircraft company’s 1-A plant down by Coal Harbour in Vancouver. “We were all broke, and I felt I should do my part for the war effort,” she recalled. “There were a lot of women working there. It was a first job for many of them, a way to get ahead after the Depression.” The women did subassembly work and inspections while mostly staying off the machines. But like the Boilermakers, the International Association of Machinists insisted that women employees receive the same wages as men for similar work. Kennedy earned more during the war than her older brother Bill, who worked as a radio announcer. She also got involved in her union, serving as a shop steward and writing a column for the union’s plant newspaper.

There were workplace issues at Boeing. As the pace of production sped up, the workers demanded two five-minute rest periods a shift. When Boeing refused, they staged a sit-down strike. After two weeks, the company gave in. Union members also lobbied to get rid of lousy supervisors. “I think we were more interested in production than management. They were more interested in profits,” said Kennedy. “It was a stimulating time. Many people who’d never considered joining a union were drawn into the movement, and it changed them.” As for the job itself, Kennedy was not as enamoured as Jonnie Rankin. “Women work for the same reason men do, not so much ’cause they love it, but that they gotta.”

In the forest industry, women worked as timekeepers in the woods and in mills. No operation was as welcoming to women as the Alberni Plywood plant, rushed into production to supply plywood for ammunition boxes, Mosquito warplane components and other war needs. As it expanded to a round-the-clock operation, the mill hired more and more women. Eventually, women made up 200 of the plant’s 250 workers. Most were young and single. Many had relocated to Port Alberni from the Prairies, where they left behind family farms hit hard by the Depression. “The mill was a lifesaver for us girls,” recalled one worker from Saskatchewan. The women were soon known throughout the community as “the Plywood Girls.” They formed a softball team, dominated local dances and had a memorable time just hanging out together, a godsend for those who had grown up isolated in rural Saskatchewan. “When you’re with a whole bunch of other ladies, it’s always going to be great,” remembered one former worker fondly. “We were happy. We had a lot of fun in that place.”

By 1944, more than seven thousand BC women were members of a union, up from fewer than two thousand just three years earlier. It would not last. When Johnny came marching home, almost all women industrial workers were dismissed. Society dictated that veterans returning to the workplace had to be accommodated. As overseas fighting neared its end, Peggy Kennedy’s aircraft union knew the wartime plants were in jeopardy. “We tried to find alternative uses, pre-fab housing or something,” she said. “But everyone was laid off after the war. The layoffs were just massive.” Women were no longer welcomed as industrial workers.

A return to domestic life was accepted, but not happily. A survey by the US Women’s Bureau, likely reflecting attitudes in BC as well, found that 75 percent of female production workers wanted to continue working for wages after the war, and 86 percent of those wanted to stay in their same occupation. Now they had to resign themselves to either staying at home or earning lower wages for more traditional female employment. “There was no other place to work,” complained a laid-off woman shipyard worker. “You went back as a waitress or worked in an office, or something like that … Nobody would hire a woman to weld anything. That was a man’s job again.”

During the war, close to a third of adult women in Canada were part of the workforce. That percentage of working women was not to be reattained for another twenty years. Yet all was not gloomy. Their integration into the workplace during the war remained a beacon for women in the years ahead. And they hardly disappeared from the workplace. Many took up jobs in the expanding clerical, retail and service sectors. Although their wages were less than those earned by women in wartime industries, they were nonetheless part of a significant new stream of women into the workforce, an evolution that author Judith Finlayson called one of the greatest social changes since the Industrial Revolution.

The need for unity to fight a common enemy had done little to stem the racism that continued to permeate British Columbia. Ethnic Chinese and Nikkei were still barred from most professions, rebuffed when they tried to enlist and remained unable to vote. Far worse was to come. Over four decades, people of Japanese descent had worked hard to stake their claim to a share of the province’s economy through fishing, farming and working in the forest industry. Despite rampant prejudice and ostracism, they had mostly done well. That changed in an instant. On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the US fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor. Canada declared war against Japan the next day. Without a shred of evidence that they posed any sort of security threat, all twenty-three thousand Nikkei in British Columbia were soon branded “enemy aliens.”

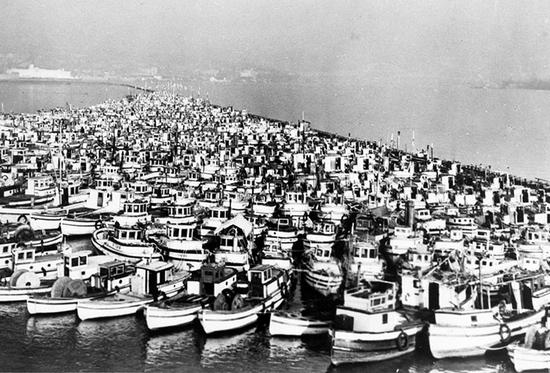

The first targets were fishermen. The very night of the Pearl Harbor attack Tsuguo Mineoka, secretary of the Japanese Fishermen’s Union, was arrested by the RCMP at his home in Steveston. Hundreds of other fishermen were also rounded up and sent to camps. But first they were ordered to surrender their cherished fishing boats. From Prince Rupert on down the coast, a forlorn procession of Nikkei-owned vessels sailed its way south. The boats were tied up at the mouth of the Fraser, left to the Custodian of Enemy Property to be auctioned off for a fraction of their value. All told, 887 seiners, gillnetters, packers, trollers and cod boats came under the auctioneer’s hammer. Most were bought by canners, who resold them to other fishermen. Others went to Indigenous fishermen.

The fishermen’s union welcomed the sale. The union newspaper The Fisherman said its workers supported “the taking of stringent precautions against dangers they have long recognized, even though such precautionary measures work hardships upon Japanese loyal to our country.” Forgotten were the earnest words of Tatsuro “Buck” Suzuki in the same Fisherman paper just four months before Pearl Harbor. Already a leader of Nikkei fishermen at twenty-six, Suzuki urged unity between the two divides. “Most of us have been in the industry for years. We are average human beings, with the same likes and dislikes as every other human being,” he wrote. “We are the weak link in the long chain of Canadian workers, not because we want to be, but because of the way other Canadians look at us and treat us. What we need is a real get-together of white Canadian and Japanese Canadian fishermen.”

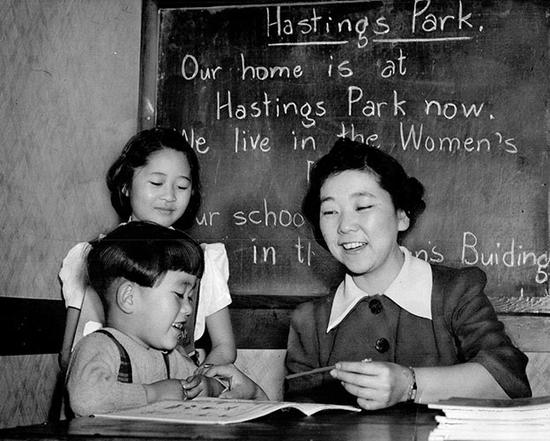

On February 4, 1942, the federal government announced that all people of Nikkei ethnicity living within one hundred miles of the West Coast would be removed, either to work camps or to flimsy wood and tarpaper shacks scattered among the mining ghost towns and small settlements of the Kootenays. Their possessions, homes and land met the same fate as Nikkei-owned fishboats, sold off for criminally low sums. Of those caught in the authorities’ shameful scoop, an estimated fourteen thousand had been born in Canada. Not one Nikkei was found guilty of a single disloyal act. “I was fingerprinted, photographed and issued an ‘alien’ registration number,” remembered Canadian-born schoolgirl Mary Haraga. “The worst part was being declared an enemy alien by my own country. I was a patriotic Canadian, but I had the face of the enemy.”

When the war ended, few wanted the Nikkei back, no matter the terrible times they had endured. “For security reasons alone, I believe no Japanese should be allowed in BC for years after the war,” said North Vancouver Liberal MP James Sinclair, grandfather of current prime minister, Justin Trudeau. More than four thousand unhappily agreed to return to Japan. The rest were scattered across Canada, barred from their home province until 1949, their lives shattered. Slowly, some Nikkei eventually drifted back to BC but nowhere near pre-internment numbers. Once thriving Nikkei communities in Vancouver and Steveston never returned to what they were.

The fishing industry was as resistant to their return as everyone else. But Buck Suzuki, who had enlisted with the British after Canada turned him down, was determined. Against strong opposition, union president Homer Stevens went to bat for him and other Nikkei fishermen. When they were threatened and harassed, Stevens lectured local union fishermen and enlisted their support. “He saw to it that we would be protected,” Suzuki told author Barry Broadfoot. “That’s the way it happened. Suddenly, the canneries took licences out of their back pocket [for us]. But it was because of the union guaranteeing our safety on the coast that we came back.” Suzuki became a revered figure within the union. A founding member of the Society Promoting Environmental Cooperation (SPEC), his passion for preserving fish habitat and the environment led the union in 1981 to establish the T. Buck Suzuki Environmental Foundation, an ongoing charitable organization dedicated to fish habitat protection.

As for British Columbia’s original inhabitants, as if governments had not done enough to strip them of rights, territory and economic opportunities, Ottawa singled them out again. At the height of the war, the federal government extended conscription to the country’s First Nations, Métis and Inuit, obligating them to fight for a country that was forcing their children into residential schools and taking their land. Ottawa further proclaimed that Indigenous fishermen would now have to pay income tax on all off-reserve earnings, which is where the commercial fishery took place. Since Indigenous people didn’t have the vote, it was a classic case of taxation without representation, on a resource fundamental to their culture and economic self-sufficiency.

Furious over both moves, the Native Brotherhood of BC and the Pacific Coast Native Fishermen’s Association merged into a stronger, better-financed Native Brotherhood with an office in Vancouver and a full-time business agent. Although the two federal measures stood, the Brotherhood emerged as one of the most effective Indigenous voices in the country, pressing for better education, health services, cultural renewal and Aboriginal rights—especially to land taken without treaties. The organization had first come together among northern coastal First Nations groups in 1931, spurred by Haida elder Alfred Adams and his vision of tribal unity. Women formed a separate Native Sisterhood of BC, supporting the Brotherhood through door-to-door canvassing, bake sales, raffles and a thrift shop in Alert Bay. The Sisterhood was also active promoting education and health. Some members trained as midwives. Where possible, they provided daycare for female cannery workers.

In its enhanced role, the Native Brotherhood began negotiating with the canneries on behalf of First Nations commercial fishermen. The Brotherhood’s first two business agents, Andy Paull and Ed Nahanee, were experienced hands in resistance by Indigenous workers. Both had been active in the Bows and Arrows longshoremen’s local on the Vancouver waterfront. The Brotherhood took part in many strikes over the years, usually in conjunction with non-Indigenous union fishermen. Increasingly, however, they felt excluded from strategy and settlements, left “holding the bag,” as one Brotherhood activist termed it. At times this led to tension with the larger United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union, which had singularly managed to unite cannery workers and fishermen up and down the coast. The UFAWU tended to be more militant than the Brotherhood, whose members were more closely tied to the canneries and included seine-boat owners.

But overall, the two organizations worked hard to maintain their common front against the canneries. Leaders attended each other’s conventions and joint negotiations prevailed, with a few hiccups, into the 1980s. Nonetheless, the Brotherhood rebuffed UFAWU entreaties to merge. Past distrust of non-Indigenous unions was difficult to shake. The Brotherhood wanted to remain distinctly First Nations. “We supported their demands for complete legal and social equality and the works,” said long-time UFAWU leader Homer Stevens, whose grandmother was Cowichan. “[By and large,] our relationships were good.”

Although their federal voting door stayed shut until 1960, Indigenous people won the right to vote in BC in 1949, leading to the election of hereditary Nisga’a chief Frank Calder for the CCF, the first status Indian to be elected to a legislature in Canada. At about the same time, legislated discrimination against Asians, which had stained the country’s history for so many years, came to an end. The vile Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1947, and citizens of Chinese, South Asian and Japanese ethnicity finally got the right to vote. “When I voted, I felt like I could finally join the human race,” said one elderly Nikkei man, whose internment during the war was only the most recent example of the marginalization and discrimination he had suffered since arriving in 1910. At the same time, a new Citizenship Act removed, at last, country of origin as a bar to citizenship.

These moves were part of a new Canada, far from perfect but moving forward, no longer steeped in the past. By the time the war was over, the country had become a respected mid-level world power on the verge of unprecedented prosperity, with burgeoning social programs and one of the best economies on the planet.

Labour’s long hostility toward Asian workers was also transformed. The International Woodworkers of America showed the way by hiring organizers Roy Mah, Joe Miyazawa and Darshan Singh Sangha to help break down the barriers of race during the union’s intense organizing drives of the 1940s.

Mah, later an acclaimed leader of Vancouver’s Chinese Canadian community, was hired by the IWA in early 1944. In addition to organizing, he put out a Cantonese edition of the union newspaper, the first of its kind in North America. After serving in the war for a country that denied him the vote, Mah returned to the IWA for two more years. He is credited with bringing as many as twenty-five hundred Chinese Canadian workers into the union.

Miyazawa got his union start during internment, helping to organize the Kamloops sawmill where he and other Nikkei found work. Afterward, he signed on as an IWA organizer in the West Kootenays, where many Nikkei remained from internment. “Wherever I was, I knew somebody, and then we’d call a meeting at the farmers’ or ladies’ institute hall or some damn thing,” he recalled of his fruitful time in the region.

Darshan Singh Sangha, son of a poor farmer, emigrated to BC as a nineteen-year- old student in 1937, but sought work in a series of sawmills instead. Dismayed by the discrimination and poor conditions experienced by Asian workers, he turned to communism and the IWA. His Punjabi pamphlets and fiery rhetoric soon had South Asian sawmill workers flocking to join the union. Sangha rose to become an IWA district trustee, the first non-white to hold such a position. In 1947, he opted to return home to be part of India’s new independence. Before leaving, he saluted the IWA’s “great achievement uniting all woodworkers—white, Indian, Chinese, Japanese—irrespective of race and colour.” Back in India, he purposely changed his name to Darshan Singh Canadian.