The Gathering In

You just said suddenly, “We’ll probably leave for home tomorrow.” You started off . . . and you arrived. It wasn’t really quite as simple as that. You probably decided suddenly because the weather was unexpectedly good for the moment and the glass had steadied. Calm, fine weather the last week in September is like a gift—something to be thankful for, but not expected. Nor do you refuse it, for it mightn’t be offered again.

Even if you had decided, the weather never definitely decided what it was going to do until ten or eleven the next morning. Once it had committed itself, it didn’t often change.

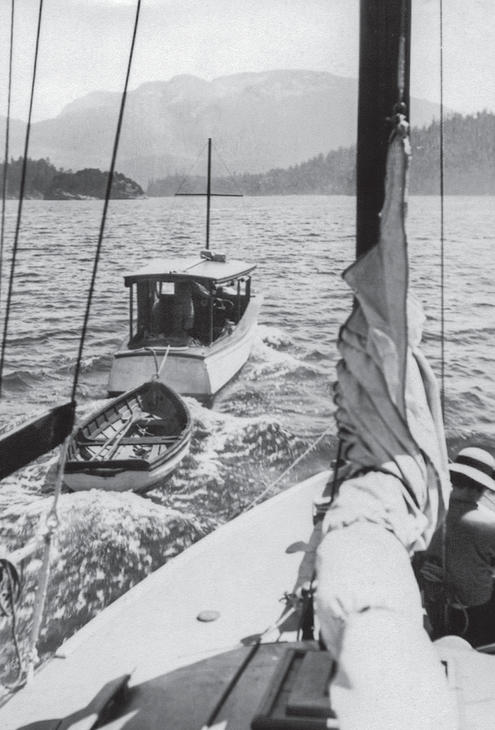

But there was always the gulf between us and home. The w eather on the home side of the gulf could be quite different from the side we were on. So in spite of it being fine and calm on the mainland side, we would take the binoculars and look across to beyond Texada Island. If you could see a long dark line on the sea extending south—then you knew that it was blowing hard from the west, the whole way down from Johnstone Strait. With our little boat, it would be foolish even to think of starting.

It is a good twelve hours’ run from Secret Cove near Welcome Pass to home. With a favourable tide we have sometimes made it in a day. But usually, we got about two-thirds of the way there and then had to hole up for the night. By the end of September in this latitude it is almost dark by six o’clock.

Once more in sheltered waters, we could start off for the last third of the trip at any time in the morning we liked. But no one had any desire to linger—home was only forty miles away. We, who had not given Little House a thought all summer, were now straining every nerve to complete the journey far faster than our boat could run.

We had come up through these waters at the beginning of June when everything was a fresh pulsing green. The small islets and points had been covered with grass and stone crop, pink sea-thrift and small blue flowers. Everything was going somewhere . . . towards some fulfillment, and was shouting out all about it. Now, in the last week in September, the hills and points were dry and brown. Green leaves were on the trees, some with a touch of yellow or a shade of pink, but they were stiff and dry and quiet. There was a stillness about everything . . . it was all spent and finished with—nothing, now, had anything to say at all.

We rushed along past them—straining for our known end. The rocky points, which like prehistoric beasts had thrust out menacing jaws to stop us on our way north, now shrank back before our urgency to let us pass.

Then somebody said, “Do you remember?” and the memories poured forth, one on top of the other . . . The hummingbird that built her nest in the rosebush just outside the window, and hatched out the black-skinned babies. The quail whose mate had been snatched up by a hawk, and who went round all spring calling, “Oh, Richard! Oh, Richard!” and Richard never answered at all. The frogs in the pond that stop singing the moment they hear a footstep, even twenty feet away, and make perfect watchdogs—but are very frustrating because you can never get near them. We never thought of Little House all summer—and now we were remembering . . .

As we made our way down the coast into home water, the maples and alders stretched like daubs of golden paint up the dry mountain sides. The grey unconcerned cliffs stood rigid as usual, letting all the changing ideas of nature sweep around and past them. Where the point gave out the evergreens climbed past and on, sturdily up the ravines and finally there was nothing left but the granite cliffs.

There was the awful cliff with the sheer drop, where the Indian Princess was rumoured to have thrown herself over. As usual the youngsters argued about the exact spot she had chosen. The three little girls each had their favourite site and wasted no further opinions.

Peter contented himself with saying, “Wasn’t she silly?” And John put his thumb in his mouth.

Now into view came the interlacing Cowichan hills—mountains really but at the moment they were only something to serve as markers of distance as we raced on at full throttle against the tide towards the “gathering in.”

Four months of each summer were spent in our small boat up the long and indented coast of British Columbia, but the focal point of our lives was Little House in the middle of the forest. The central point or focus in Little House was the big stone fireplace in the corner of the living room—and the word hearth and focus both have the same meaning—the place of the fire.

Each fall when the days got shorter and the nights got colder and the maple lit their warning signals, Little House reached out, gathering us in. We could feel her gently tugging at us across the gulf and up the far coast. As long as the sun shone and the weather pattern was tranquil we turned a deaf ear and closed our minds. But a time always came when the big southeaster kept us tied to a sheltered bay—or worse when it wasn’t sheltered and you spent a couple of miserable nights up every hour checking your bearings. The morning would show the whole gulf a sullen mass of great heaving waves with billowy white crests.

Following a usual pattern, the wind, when it had exhausted itself blowing from the southeast would storm around to the west, pushing and struggling against the southeast swell it had created. By that time we would all be straining toward Little House. But there was nothing we could do but wait until the gulf was quiet, then take our chance and get across.

Then there was the last home stretch with the islands opening out one by one to let us pass. Our Gordon setter was standing up in the dinghy now, her tail wagging. We didn’t know what she was recognizing, but she knew we were home. The tide was still too low to land our equipment so we anchored off Little Cove on the south and rowed ashore. The arbutus trees that had been in bloom when we left in June were now ablaze with bright red berries. How tall the forest was, and still! The path was covered with crisp dry arbutus leaves that fell in June and our feet scrunched them as we trod over them through the trees. There stood Little House. The great maple behind glowing yellow and orange like a halo over her head.