Little House

I remember when we first found Little House, lying all by itself in the middle of the forest. It was June-time. Everything was covered with the roses in bloom—on the paths—in the porch—over the house—up the roof . . . roses were everywhere. They formed a cordon round the house—we couldn’t get near it. They caught at our legs and tugged at our clothes. “It’s ours, it’s ours!” they cried, and did their best to keep us out.

It was the first time we had ever found a little fairy tale house in the middle of a forest, and we didn’t know quite what to do. So we called out, “Little House, Little House, who lives in Little House?” and nobody answered.

So we called louder, “Little House, Little House, who lives in Little House?” And still nobody answered.

“Well, then,” we said, “we’ll live here ourselves,” and we crept in through the window and settled ourselves in Little House.

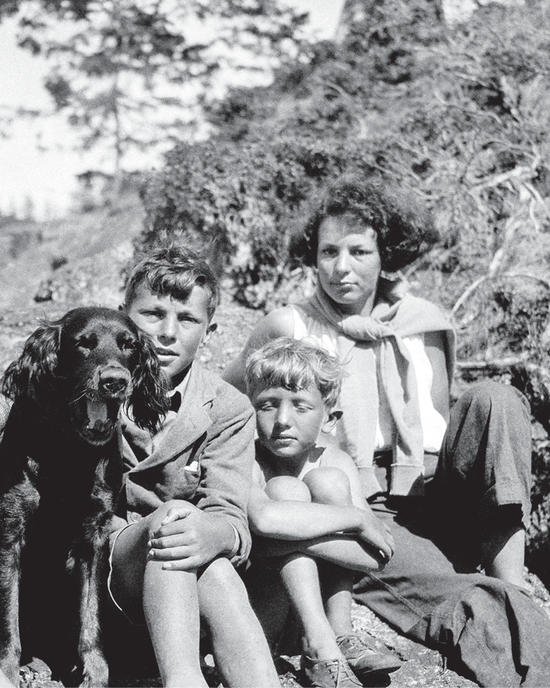

That was the tale the children used to tell on winter evenings, in front of the roaring fire in the big stone fireplace, about how we came to live in Little House. Just when everybody was feeling happy and contented about it, Peter always broke the peace by saying, “You’re not in this, John, you weren’t here at all.” And John always said, “Well, I came along suddenly, and when you all answered, I said ‘I’m Mr. Bear-squash-you-all-flat,’ and I squashed you all flat as anything.”

You would understand all this better if you had read our favourite book of the moment, Russian Picture Tales. In one of the stories, a mouse finds a big earthen water jar lying in a field, and thinks what a nice house it would make to live in. So he says, “Little House, Little House, who lives in Little House?” and nobody answers. So he calls louder . . . and when still nobody answers, he says, “Well then, I shall live here myself.” So he settles himself in Little House. Then a frog comes along and asks the same question, and when Mr. Mouse answers that he, Mr. Mouse, does, they decide to live together. Several other animals join them, the last being Mr. Bear-squash-you-all-flat, who comes along suddenly and spoils everything by sitting down.

Anyway, our Little House looked just like a fairy tale house. It was built of half-logs with the rough bark still on, all up on end. The casement windows, in groups of three, had leaded panes. The roof was very steep, also of bark, with a great stone chimney breaking through on one side of it and a gable window on the other. There was a porch at the front of the house, and beside the porch grew a great rose bush with a trunk as big as a man’s arm. It climbed up over the steep porch roof and peeked in through the leaded-paned windows of the upper room. Then, since nobody would let it in there, it scrambled up under the wide eaves and tried to find cracks into the attic, or pry the bark off the logs on the roof—for it was a very strong rose bush and had no shame.

After we had called out and asked who lived in Little House and crawled in through the unlatched window, we lost our hearts to it. For inside was a great square living room with a big stone fireplace across one corner, and a winding staircase in another. Long groups of windows with diamond panes looked deep into the green forest that crowded close. As you shrank back—a little dismayed at such dangerous living—the low dark ceiling spread itself over you, and you at once felt all right again.

Then we tiptoed through the echoing dining room; looked into the silent kitchen; crept up the winding staircase to the bedrooms, where the wooden walls sloped steeply and made the ceilings seem on strangely intimate terms with the floor.

Anyway, there it all was—fireplace, latticed windows, winding stairs, low dark ceilings and of course roses . . . one was rather helpless against them all.

When we crawled out through the window again, there on the ground right underneath the window was a round silver dollar. We considered that a very good omen, and spent it on ice cream and salve for the thorns.

Seven acres of its own land surrounded Little House. On three sides was the sea, and on the fourth side the big forest. If you hold your right arm and hand, palm up and slightly cupping the hand, thumb close in—you have a relief map of Seven Acres. You approached, as though along your arm, through half a mile of forest with the sea on your right. Seven Acres began just before you reached the hollow that your wrist makes with the joint of your thumb as it swings out. This hollow was called Big Cove—a sandy cove that cleft the high cliff for no apparent reason.

Little House faced south and slightly east, and a garden ran from the house to Little Cove—which was where the big cliff ended. The ball of your thumb and the thumb itself was the rugged cliff which rose two hundred feet up from the sea and sloped abruptly to your palm. The driveway skirted the inner base of the cliff or ball of your thumb, along where your Life Line and Line of Destiny run. And where your lines of Life and Destiny meet your Heart Line, there nestled Little House. And here too, Life and Heart brought Destiny to us.

Destiny rarely follows the pattern we would choose for it and the legacy of death often shapes our lives in ways we could not imagine. Death comes to everyone in their time—to some a parting, to some a release. We who are nearest go with them up the long golden stairs—up—up. A trumpet shrills—a gate clangs and we are left standing without. Then down the long stairs we retrace our steps to earth—an earth that is all numb and still—so still that one hears strange sounds—catches strange vagrant notes on one’s heightened senses.

But small hands are tugging and voices are insistent.

“Will he ever come back from that other place?”

“Oh no, he doesn’t want to come back!”

“Does he like it there?”

“Oh yes, he loves it.”

“Well then, that’s good.” And happy laughter rings through the tall green pines and along the rocks and sandy beaches by the sea.

No one grudges him his place in the sun.

A very special counsel was held in front of the big fireplace and summons were dispatched by Mrs. Bear to Miss Elizabeth, Miss Lou, Miss Jay and Mr. Peter.

“Of course I’ll be there too,” said Mrs. Bear.

It was the beginning of October and the evenings were to close in early. I knelt down and put a match to the fire in the big fireplace and while I waited for my fellow councilmen, I once more read the letters that had come that afternoon. They were full of underlined words. What one letter forgot the other ones said. “Impossible, impossible . . . impossible . . . not fair to the children. You’re far too young to isolate yourself in that isolated place. Pack up at once. Just send a telegram.” How nicely they had my life planned out.

I was still muttering and growling when Mr. Peter came in and seated himself panting on the council rug.

“Are you mad?” he asked glancing from my face to the letter.

“Grrrrr,” I muttered.

Peter sniffed cheerfully. This was evidently going to be an interesting council. Miss Jay came in and seated herself beside him.

“She’s mad,” he whispered.

Jay dug her elbow hard into his ribs and ignored him. Little boys shouldn’t be encouraged to speak of their mothers like that.

Then Miss Lizbeth took Mrs. Bear by the hand.

“It’s dash as dash,” said Mrs. Bear. “Where’s Miss Lou?”

“She’ll be here just in a minute, she’s in a boat and she has to anchor it.”

“In a boat?” I jumped to my feet.

“Mummy, Mummy,” they all cried, “It’s just in the woods.”

“Oh,” I said sinking back, “that kind of a boat.” Even I knew how it was to anchor that kind of a boat and as for Miss Lou, a nother name she went by was, “Linger-Longer-Lou.”

High leaped the flames of the council fire and the case was put before them . . . Go back to town—leave Little House!

Tears flowed freely. The only thing I was able to gather at all was that everybody thought as I did. It would be impossible to leave Little House. Then when things dried up a bit we discovered that John was missing. Though he was only two and a half, John never allowed anyone to see him crying. If tears must come, and they quite often did, he shed them in private, under the stairs, in the cupboard, in Pam’s kennel. No one was under the stairs. No one in the cupboard. I opened the back door. Pamela was half in, half out of her kennel and looked at me reproachfully with her liquid eyes. “What have you been doing to your offspring?” they enquired, and looked anxiously into the kennel.

“John,” I called kneeling down.

“I’m not going to that old city,” said a tearful voice. John who had never been to a city. “I’m going to live here with Pam.”

I sent the telegram off the next day. It wasn’t very polite—and I didn’t care much. “Can’t I?”—and did.