Seven Acres

After a big storm we always had expeditions and explorings to find out how many trees had blown down and what had been cast up on the beaches—the choice depending on how strong the wind had been.

If we were going to the forest we would start off in pairs in different directions, our boundaries being fixed by mysterious points such as the Big Cedar, High Mound, Upper Water Hole, Mink Run and others that the children knew. Armed with bows and arrows and stout sticks and packages of sandwiches in our pockets we would separate. Two would go along the north sea trail, two up the back trail and John and I up the central trail—all to meet at the outer gate before the sun went down. It never worked out quite that way. How could anyone wait until the sun went down to report on an important find? Also after the sun went down one’s feet turned instinctively toward Little House—shadows might be anything. All during the expeditions explorers would crash through the forest demanding that we detour to inspect this or that find. After we had finished sorrowing over the death of a tree that Christopher Columbus might have known we would hastily compute how long the bark would last us for burning—if it were a Douglas Fir. Then we would all take mental notes of where the tree lay so that we could find it again, and off we would go our separate ways once more.

Once John and I made the biggest discovery, and the most exciting. A huge fir was down right across the road. So John and I shouted and hullooed until the other two parties broke through the forest. The big trunk had to be measured—about four feet in diameter we agreed. Then we stared blankly at each other realizing that it was also four feet of barricade and that we couldn’t get our car out until the tree was sawn up. Exploring forgotten, we had to make our way down to the nearest farm and tell the farmer about our trouble. He was full of his own troubles. After we had exchanged troubles, we agreed that ours was the most pressing and that he would come out in the morning with the big saw and the sledge and wedge and we would saw our way out.

The farmer’s wife had made us hot tea as the day was cold and snow lay on the ground. When we went outside again, the sun was long since down. I thought uneasily how dark it would be in the forest. The farmer perceived this and lent us a little lantern. The glass was smoked up and the wick needed trimming and it made fearsome shadows all its own. We went up the long lane from the farm, hurried up the hill and then holding hands we took long breaths and entered the forest.

How still a forest usually is! But after a big storm it is also uneasy and passed its uneasiness on to us. Uprooted trees after all are still alive and they are not used to this new position. Now and then a protesting branch would liberate itself with a sharp crack. Something snuffled and there was the sound of claws scratching on bark. A coon probably. But the heart thuds and the children crowd close to one’s heels. We have to go in single file finally and Elizabeth holds the lantern higher and two shiny eyes gaze at us. We let out sighs as it bounds off.

“Deers are nothing,” says Peter stoutly, holding on to my coat tails.

Then down the canyon hill, Big Cove lies quietly on our right; up canyon hill and now we can see sky and stars over our heads as we enter the clearing. There is the dark outline of Little House. A few more steps and the explorers break into a run. We cut around to the back door and push into a warm kitchen and oh, the blessed sound of a closed door.

It is November today and I found a little lizard, brown and orange below, standing on the cold cement floor. I stooped down to look at him. If it had been warm he would have disappeared in a flash. He was sluggish and also cold. You could feel the ton weight that held each foot from moving.

There were a dozen or more quails out in the sand pile scratching up the pale succulent roots that sand piles seem to produce. Now the quail began to jerk nervously. That means they are about to make the perilous run past the window to the flower bed. Their feet all twinkle together as they fly past and duck for shelter under the worn out weeds and naked shrubs. Then they begin to scratch and dig again, their little topknots bobbing and bobbing and bobbing. I wonder if it has uses as antenna. They are so quick to sense and transmit the slightest sound. Whizzzzz and in a burst of wing they are gone. I wish I were an artist—such simple vigorous lines would draw them. Two sharp parallel white lines on the back where the wings cling close to the body. Then more sharp white strokes at an acute angle outlining the primary feathers. The strange little black velvet mark edged with white held on with white strings over the ears. Then the scalp-lock gathered up and surmounted with a bobbing topknot.

I surprised them late the other afternoon. I cut across the path by the cedars where there is an eight-foot pole that supported a great round clump of ivy. They flew up from under my feet as I reached the cedars but instead of flying off out of sight they flew up, and dropped feet first into the bush. I clapped my hands and sure enough the ivy exploded quail in all directions.

Today a hawk chased a little quail bang up against the kitchen window. Then she sat on the window sill and shrieked. I went over to look at her but she yelled at me and said she had had all she could stand at the moment and flew off, still shrieking.

Yesterday I thought the snow was over and I swung the axe with a reckless flourish that buried it deep in the chopping stump—and then with an equally reckless glance at the chimney, I made for the woods.

The afternoon is short in the winter and I wandered through the trees enjoying and drinking in their beauty. Every branch was laden and the slightest touch brought a silvery shower down on me. I strode through salal, each leaf piled to capacity. What matter if my boots were full of feathery loveliness? Hadn’t the cold weather broken and wasn’t it good to be alive? How cold the arbutus trees looked, standing sullen in their nakedness.

Back at the house I piled the fireplace with wood. That night secure in my faith that the need to stoke all night had passed, I climbed into bed with never a thought for the axe I had left in the chopping block.

Somewhere in the middle of those hours when the physical body is at its lowest ebb, I woke up. Out in the Straits fog horns wailed like lost souls. I crept out of bed and donned dressing gown and slippers and went downstairs to an almost dead fire. The clock in the flickering light showed half past two and I piled on my last remaining wood and slipped back to bed.

At half past seven I awoke again. Fog horns still moaned out in the Straits and a blinding snow drove in from the north. My breath rose like cumuli in the still room and I burrowed miserably remembering my empty wood pile and axe on the block.

Then outside my window, on a snow covered branch under the eaves a sparrow who had probably felt reckless too sang, “Why fret, why fret? Spring’s coming yet.”

The frogs are fairly shouting in our pond today. It has been a very late spring with some of our coldest weather after the fifteenth of March. So I suppose this business of getting the next generation under way has been somewhat delayed. A month ago I heard a few timid notes and the next day all was quiet and ice and snow had covered the pond. A whole month lost.

So today Peter and I sat on our heels right beside the water and they paid no attention whatever to us. Double circles here and double circles there in the water and, with only a nose above, out would go their clear trebling to wherever the deep thrummers had holed up for the winter. Or had they? Of if they had, where? This pond life is very new to us. Four summers ago we had a hole bulldozed out for a large reservoir. When the fall rains came it turned into a pond. Late that fall a muskrat appeared and spent the winter holed up somewhere in the banks of our virgin pool. There are no lakes or streams within five miles of us so he must have come by sea. But who told our seafaring muskrat about the new pond in the middle of the forest?

The next spring, someone must have told a frog, for two or three were trying it out. That summer the news spread and life came to our pond with a rush. A lone bullrush pushed its way up in one corner, saw its own reflection and stayed. And with whatever a growing plant brings to a pond that helps water support life, came the skating bugs that cut intricate figures on the surface of the water. The little black oval scuttler beetles that dart around half submerged and willy-nilly grab any mate, came too. Soon there was plenty of food for the polywogs that wriggled around on their burrowed tails and survival was high.

Now, this fifth spring, the pond where Peter and I sit on our heels teems with all that mysteriously arrives to create a living pool. Bullrushes are breaking water in at least half the area and last year’s growth still stands waist deep, dry and crisp. The frogs, perhaps brave with numbers, are trebling in sheer abandon and no movement of ours will stop them. We see a stir of green in the dry grass at the pond’s edge and I pick up a little green peeper. How cold he is. His little transparent pink fingers so frail and jointed and slender lie timidly touching my palm, while its cold stomach supports its weight. His throat pulsates and he looks very worried. It seems very fat of stomach and so we decide it is a she and perhaps that explains the unwary shouting that won’t be stilled.

“What is he doing, the great god Pan, down in the reeds by the river?” I asked John.

“Splashing and paddling with hoofs of a goat and breaking the golden lilies afloat as with the dragon fly in the river,” answered John cuddling down beside me in bed. “Didn’t you know?” he asked.

“Oh go away,” I murmured sleepily.

“No we always do,” waxed John indignantly.

So there was no hope. I had to waken up. But it was very pleasant lying in bed with a little boy, telling each other all about Pan. Down below we could hear Elizabeth busy with the kitchen fire. The sun was coming in the open window and setting the lattice alight. Soon we knew there would come the call for a swim, and we would leave to go to splash and paddle in the sea, like Pan. No one could have excuses on a sunny morning.

Yet through it all ran a thin thread of routine. Elizabeth’s tawny head came in the door. Tawny head, tawny eyes. Lion’s eyes we called them.

“Porridge made,” she announced. “Swim you two!” The head disappeared.

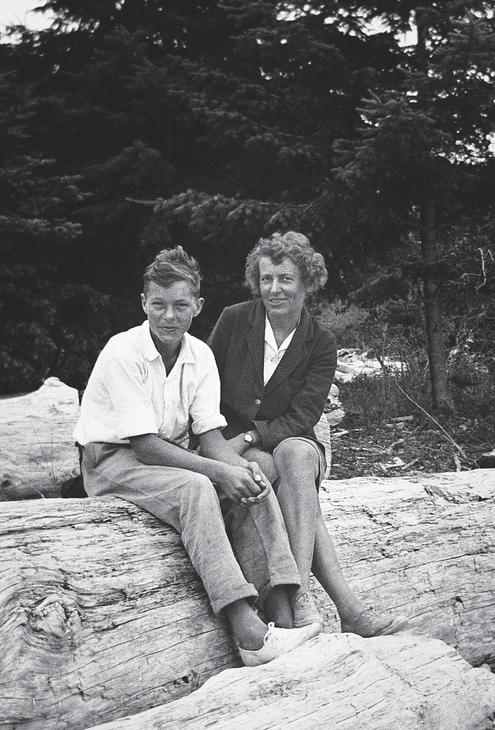

John and I giggled. From the noise in the back bedrooms the rest were not treated so gently. Then shrieks of laughter and a wild rush of feet down the stairs. The front door opened and they spilled out of Little House into the early sunshine.

“Come on, come on,” they called.

Except for the little fertile garden, Seven Acres was mostly trees, rocks and cliffs. If you went up the hill to the east there was a ridge and the house disappeared, all but the pointed roof. If you climbed the big cliff to the southeast and looked back, you saw nothing but treetops and sky, and you thought, “Oh, dear! What has happened to Little House?” But if you remembered to look down at your feet, then you found it again—for ’way down a thin thread of smoke was rising up through the treetops.

Most of the trees that grew on Seven Acres were Douglas firs, that went up and up—great bare trunks. But far up at the top, if you held your head back, you could see the branches sprawled against the sky. Here and there among the firs were arbutus trees. They were green all the year round, shedding their old leaves as the new leaves came. They also shed their red bark and stood there cold and naked-looking, their satin-smooth skin now the palest pinks and greens. They are versatile trees, for they also bloom in the spring, holding up what at a distance look like little bunches of lily-of-the-valley. Not content with that, the flowers become bright red berries in the autumn.

When we first lived there, the big firs and balsams grew very close to the house. So close that they could lean across and whisper to each other at night. Sometimes they would keep you awake and you would forget and say sharply, “Hush, trees, go to sleep!” At first there would be an astonished silence . . . then a rush of low laughter . . . and they would whisper louder than ever, until you had to put your head under the blankets.

The coast of British Columbia is what is called a sinking coast. At some time, long past, there had been a great upheaval, and then subsidence. Seven Acres did not escape. Some awful force picked it up, held it at arm’s length, and then let it drop sideways in an untidy muddle. Some of it held together, and the rest of it lay here and there. You could never go out for a straight stroll—you were always climbing up something, or clambering down something, making a detour. When you wanted to get to the top of the big cliff it took you ages to get there. First you had to go along the driveway. Then cut down to the left through the little copse of wild cherry and cedar. That brought you through to a half a dozen rough stone steps that led up and round a great block of stone onto a straight path. But just as you thought this might be leading somewhere, you found yourself on a long winding serpent of stepping-stones that writhes in and out, and up and down—but always higher and higher until finally you sank down breathlessly on the very tip-top of the big cliff.

If you peered cautiously over . . . you could see great blocks of rock that had broken off the cliff at some past time. You would step back from the edge and look anxiously round for signs of more cracks. There was a dry reef a little way offshore, and on it cormorants sat and spread out their wings to dry between dives. Sometimes the seagulls passing would stop and gossip for a while with the cormorants; or a seal haul his fish out on the lower ledge and enjoy it in the sun. On calm days you could lie and watch the little helldivers dive down . . . down . . . down in the clear green water—and follow the quick turns and kick of their little pink feet, and the line of bubbles that drifted to the surface.

The smaller cliff to the east had been left on its end by the long past upheaval. All the strata, instead of lying horizontally, ran up and down and bent into groaning curves. The rock was soft, and wind and waves had worn it away until the top of the cliff was overhanging. Sixty feet above the sea, at the very edge and nonchalantly stepping off into space, poised a stunted fir tree. Time and the weather had worried and worn it—but there it persisted, sharp and simple as a Japanese print with the sea and snowpeaked Mount Baker in the background.

Island after island lay to the east and north of us. The tides in this area have a normal rise and fall of fifteen feet, though with a high wind they pile up two or three feet higher. Twice a day, these tides came and struggled through the narrow passes, pushed past the blocking islands and up the deep bay and inlets. And twice a day they gave it up and ran exhausted back to the wide ocean.

The islands sheltered us fairly well from the cold north winds, but we were open and exposed to those from the southeast. The big winter winds from that direction would drive in from Puget Sound and Juan de Fuca Straits. Higher and higher would rise the tide and the seas. With great booming roars the waves would fling themselves against the cliffs, dashing and battering them in blind fury. The coves would be a seething mass of swirling logs smashing themselves into futile splinters and scouring the beaches out of all recognition.

Salt spray from the crests of the big waves was caught up by the wind and blown a hundred yards inland—right up to Little House itself. Branches hurtled through the air and landed with deep crashes. Nobody dared to go out of doors. In the worst gusts a whole tree would fall with a mighty thud that jarred the whole house.

Then driving rain . . . dying wind . . . and finally peace. Seven Acres, stripped of everything weak or unsound, would shake the wet from its strong sound branches; run the water off its steep rocks and cliffs, and stand steaming in the misty sunlight.

. . . Yes, yes! We all remember . . . Hurry! Hurry!