Author’s Foreword to the First Edition

This is neither a story nor a log; it is just an account of many long sunny summer months, during many years, when the children were young enough and old enough to take on camping holidays up the coast of British Columbia. Time did not exist; or if it did it did not matter, and perhaps it was not always sunny.

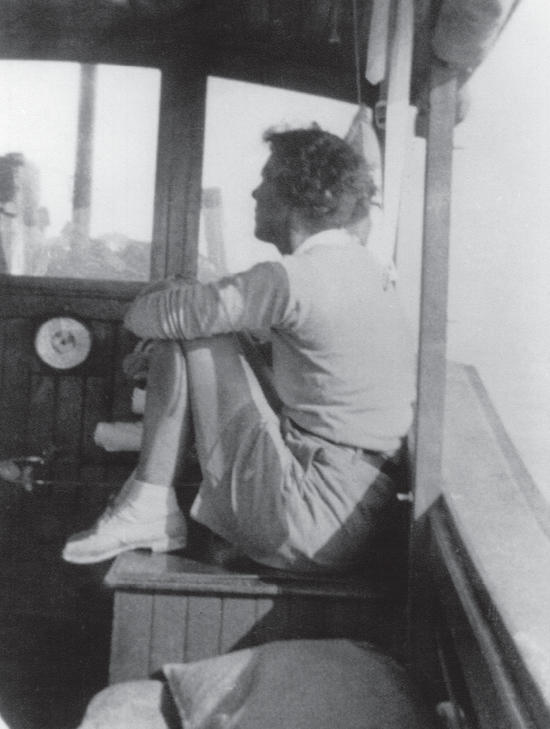

Our world then was both wide and narrow—wide in the immensity of sea and mountain; narrow in that the boat was very small, and we lived and camped, explored and swam in a little realm of our own making.

At times we longed for a larger boat; for each summer, as the children grew bigger, the boat seemed to grow smaller, and it became a problem how to fit everyone in. She was only twenty-five feet long, with a beam of six and a half feet, and until later, when the two oldest girls went East to school, she had to hold six human beings and sometimes a dog as well.

There were narrow bunks in the cockpit, butting into what we called the “back seat” which ran across the stern. Elizabeth slept in one, over the bedding and clothes locker. I slept in the other, over the gas tank and small food locker. We were quite comfortable. It was Peter, sleeping on the back seat over the big food locker, who complained when we slipped down too far in our bunks and got tangled up with either his head or his feet.

Up in the engine-room, which was separated from the cockpit by a solid bulkhead with a small door, there was a wedge-shaped bunk just for’ard of the engine. It started off with a width of four feet, but tapered to six inches in the peak. That was where the two smaller girls slept. There was no headroom in there—we had to crouch to get through the little door, and we had to crouch all the time we were in there—unless the hatch was open. But the children were quite comfortable, and with the hatch open at night they could lie there tracking down the different stars they knew, and gradually adding others.

That left John. John slept on a long pad down what he called the “crack,” which was the eighteen-inch space between my bunk and Elizabeth’s. In the early days no one could think what to do with John, until he solved the problem all by himself. We were busy one afternoon, cleaning up the boat, and nobody was paying any attention to what he was doing on shore. Once he came back to get the saw; then he spent the rest of the afternoon on the beach, very busy over something. Just before supper he climbed on board—the saw under one arm and a neat bundle of wood under the other.

“I’m not going to sleep down that old crack any more,” he announced, as he spread out his bundle of wood and showed us. He had sawn up twelve twenty-two by three-inch boards and joined them all together with heavy fishing line, like a venetian blind. It fitted across the space between the two bunks, and under the two mattresses. The slats could not slip apart, for the line held them; yet it could be rolled up in the daytime and easily stowed away. The long narrow pad still fitted. He had anticipated all possible objections—there was nothing we could say. John had thought of a way to get himself up out of that crack, and was up to stay.

There was a two-by-two-foot steering seat just for’ard of Elizabeth’s bunk, over a locker that held pots and pans and everyday stores. The gasoline stove fitted on top of the steering seat when in use, and folded up like a suitcase for stowing away. Its place was between the five-gallon demijohn of water and my bunk. Everything had to have its exact place, or no one could move.

We were very comfortable in the daytime with everything stowed away. The cockpit was covered, and had heavy canvas curtains that fastened down or could be rolled up. There was a folding table whose legs jammed tightly between the two bunks to steady it. And it was camping—not cruising. We washed our dishes (one plate, one mug each) over the side of the boat; there was a little rope ladder that could be hung over the stern, and we used that when we went swimming.

We may have grumbled about the accommodation; not about the boat herself. Lightly built (half-inch cedar) and well designed, she never hesitated to attempt anything we wanted her to try. She was uncomfortable in much of a beam sea, so for all our sakes we humoured her by working crab-fashion along the coast, first one way and then the other. But it was a following sea that she loved best; and after a long, tiring day it was never by her wish that we would give up and slip in to the sudden calm of a sheltered anchorage, where she had to lie, all quiet, and only gently stirring . . .

Four of the stories in the book have appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine.

M.W.B. Vancouver Island British Columbia