Foreword

by Michael Blanchet and Judy Reid

The author of this book, Muriel Wylie “Capi” Blanchet (1891–1961), was our grandmother, and we are delighted to endorse this expanded new edition from Harbour Publishing. After more than six decades in print through at least five editions and countless printings, The Curve of Time is justifiably described as a Canadian classic. We are still surprised by the excitement it arouses in people.

A few years ago, while Judy was in a bookstore in Vancouver, it came up that her grandmother was the author of The Curve of Time. The staff quickly surrounded her, eager to talk about their love of the book and how popular it was with their customers. Almost any mention of the book to boaters on Vancouver Island brings the same response. It has thousands of fans, and whenever any one of them discovers our family connection, they always want to know what Capi was “really” like. There is no simple answer to this question.

Michael remembers first encountering Capi when he was five years old. His father, Tate, was the elder of Capi’s two sons and had served as a deckhand on the Caprice’s summer voyages from the age of eight until, at sixteen, he left to attend the University of British Columbia. Tate and his brood of eight children—including Michael—were living in Calgary when Capi came to visit. Suddenly, their easy-going household was turned upside-down. Capi was a formidable presence who insisted on being in command and no one questioned her authority, including Tate—normally no pushover himself, as Michael can attest.

A word about names: In writing The Curve of Time, Capi often blurred the names of places and people, including those of her own children. Between birth names, nicknames and made-up names it can seem like she had a crew of fifteen rather than five. Her eldest daughter, Betty, (1913–1995) was referred to in the book as Elizabeth, her given name, although we never called her by it. Judy’s mother, Frances (1914–1996), was left with her given name, which was also her everyday name, Frances. But Joan (1916–1999) was renamed in the book as Jan. Michael’s father remained Peter (1919–1997), which was his actual birth name, though in real life he was always known as Tate, a childhood nickname. David (1924–1981) appeared in the book as John, also a never-used birth name.

Shortly after Capi’s memorable visit to Calgary, Michael’s family moved to Vancouver. This meant that they were privileged to receive more frequent visits from their bossy granny, which, for the children, meant finding a place to hide for the duration. It also meant visiting Capi at her house on Vancouver Island just north of Sidney.

Her seven-acre property was known as Clovelly. The house was on a peninsula on the other side of a hill from what is now the busy ferry terminal at Swartz Bay. Canoe Cove is on the east side of the peninsula, along with a collection of small islands. At the southern tip of the peninsula, at the end of what is now known as Tryon Road, is Curteis Point. Capi’s house was on a crest above this point, looking through the forest toward the water with Mount Baker in the far distance. We remember swimming in the beautiful waters of the southern Georgia Strait, spending nights listening to stories in front of the huge fireplace and sleeping upstairs in rooms with large wooden windows. The house we grandchildren remember was actually her second house at Clovelly, built in the early 1950s. The original house, which is the one referred to as “Little House” in the book, had fallen apart after providing shelter for three generations of the family. It also provided income when Capi rented it out to help finance the summer boating excursions.

Clovelly was a wonderful place to visit when we were kids, but the fun was tempered by the stern demeanour of our omnipresent grandmother, who seemed to be casting a watchful eye on our every movement. We would wonder what it must have been like when our parents were our age, having to live with Capi all the time, especially in that cramped little boat.

We would hear many stories from aunts and uncles of their experiences with Capi. Our uncle David’s widow, Janet, is ninety-three at this writing and is the only family member of our parents’ generation still living. She has many amusing stories from when she and David, early in their marriage, lived with Capi at Little House. There was only one light bulb in the living room and when Capi would go to bed, she would unscrew the bulb and take it upstairs with her to read by, leaving David and Janet in the dark. Janet also remembers Capi’s innovative method of washing dishes: She would take her dirty, chipped dinner dishes and mismatched silverware down to the beach in a bucket and leave them for the crabs to pick clean. One time, when she went back down to pick them up, they were gone. So she put an ad in the local paper, which read, “Would the people seen taking my plates and cutlery please return them?” The spot where she’d left the dishes couldn’t be seen from the house, but there was no way the culprits could know that. The bluff worked. The missing items miraculously reappeared in a box a couple of days later with a note that read, “If you seen us take them, why didn’t you say something?”

By the early 1950s, Little House was falling down, so Capi teamed up with Uncle David to build a sturdier new one. But it was never quite finished: Doorknobs turned uselessly and the bathroom had no door, just a makeshift curtain on a wooden curtain rod that would be moved to one of the bedrooms at night. For heat there was only a wood-burning kitchen range that constantly went out and a large fireplace that seemed to suck all the heat up the chimney. Janet said it got so cold in the winter that water would freeze in the kitchen kettle. Later in the 1950s, Capi relented and replaced the wood-burning range with an oil range but felt it a waste of fuel to light it before noon. This presented a problem when it came to cooking her morning egg, which she got around by placing the pot on an upturned electric iron. She found another use for the oil range when she was diagnosed with emphysema and doctors advised her to move to a warmer climate. Instead, she took to lying on a chair with her head inside the oven for a period each day. “This is my warmer climate,” she would say.

No hardship seemed to bother Capi, who was endlessly adaptable and resourceful. Judy’s father, Ron King, tells a story of visiting during World War II, when Capi was still in Little House. He arrived at Clovelly to find Capi down at the dock working on the Caprice’s famously temperamental engine. She had the Kermath all in pieces and was in the process of grinding the valves and replacing the piston rings. Ron had worked in a garage and recognized this as work that would normally only be attempted by an experienced mechanic. It forever cemented in his mind that Capi was a force to be reckoned with, although she typically made light of her skills. She had the attitude that she could do anything a man could do—and often proved it—but did so without forgetting her private-school good manners. Her worst curse was, “You poor fool!” She wasn’t one to fuss over her appearance. Her favourite costume while out on the boat was a short-sleeved blouse and shorts that hit mid-thigh, which was still very risqué in the 1920s and got a lot of attention from upcoast handloggers (though she apparently didn’t mind). Back home, her usual garb when going shopping in Sidney was a straw hat, an old pair of overalls and a much-used backpack.

She was very stoic and took charge of family crises without showing emotion. Her nickname growing up had been “Toughie” and it was apt. Tate said he only ever saw her cry once, when he moved his family to Peru. Perhaps the greatest example of Capi’s stability was following the death of her husband, Geoffrey, who took the Caprice out for a cruise one September day in 1926 and disappeared overboard, never to be found. The first thing most people would have done in Capi’s situation—widowed at thirty-five, with five children ranging in age from three to thirteen, and without significant means—would be to sell the boat involved in the tragedy. Instead, Capi coolly took stock of her position, declined offers of refuge from her Ontario relatives and decided not only to keep the Caprice, but to use it to provide her children with a memorable upbringing exploring the far reaches of the BC coast.

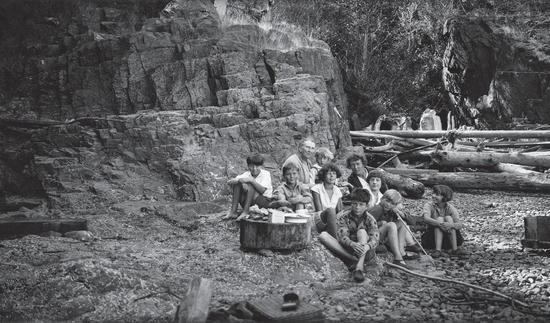

Judy’s mother, Frances, had fond memories of those summers at sea, which she joined on and off between periods of attending private school and nurses’ training. Her journals describe voyages on the Caprice as an endless rush of activities, with bonfires and picnics and visits with good friends along the way. She remembers gathering blackberries and huckleberries, and hiking at 5,300 feet on a carpet of heather, mosses and alpine flowers. Picking apples at an old homestead and making applesauce on their portable stove. Sunbathing. Knitting and reading while it rained. Being mesmerized by the explosions of phosphorescence in the night sea. Playing badminton and dancing with friends on their veranda. Swimming in lakes; rowing. Frances cherished memories of the family excursions and was very proud of her mother’s book, which she often gifted to friends and family. On the inside cover of Judy’s copy she wrote, “. . . that you may know how I spent my childhood.”

And what kind of a childhood was that? Certainly not one the helicopter parents of the 2020s would approve of. Capi exposed her children to danger but also to high adventure. She taught them how to survive and how to experience nature in the raw. The children were largely homeschooled, although the two older girls did attend private schools part of the time. It was unorthodox parenting even for its time, but the results can’t be disputed. The two boys achieved university entrance at the unlikely ages of sixteen and seventeen. Tate became a geological engineer and went on to a distinguished career in mining and business. David had a genius-level IQ and could do anything he set his mind to until being disabled by polio. Betty became a writer of some thirty popular novels and, in her eighties, earned a university degree. Frances was a nurse-turned-rancher and recognized amateur birder. Joan studied art in New York and once alarmed her mother by showing up at Clovelly in a dugout canoe, having paddled across Georgia Strait singlehandedly in the dark of night. Capi’s response was interesting: “It’s alright for me to make a fool of myself, but that doesn’t mean you have to!”

The summer cruises wound down with the coming of the war in 1939, although apparently some were made as late as 1942. Not only were the children by then setting out on their own careers, but gasoline was rationed and pleasure boats were largely tied up. Not one to sit on the sidelines during a war, Capi painted the Caprice grey and participated in volunteer patrolling of the coast. In those same years, military personnel were stationed at the Patricia Bay air base, not far from Clovelly, and visiting English officers were often invited over to partake of Capi’s baked beans and brown bread.

Even after the kids grew up, Capi continued to have occasion to reprise her maternal role. Frances was expecting her first child when her husband, Ron, was shipped overseas, so Capi took her in for the duration. When Frances went into labour, she rowed herself over to Sidney, where she gave birth to a son, Bobby, at Rest Haven Hospital. For eighteen months while Ron was overseas, Frances and Bobby continued to be sheltered under Capi’s roof, joined by Aunt Betty and her little boy, Brian, who stayed until 1946. Eventually the families went on their way—except David, who stayed to build Capi’s new house, as well as one for himself and his wife, Janet, until he was stricken with polio. Then Janet had to move to Victoria to work for the government and Capi was once again called upon to care for a child: Julia, who was David and Janet’s little girl. Julia has said during this time she felt more like a youngest child than a grandchild. She remembers Capi as having a wonderful sense of humour and a fondness for ice cream, peppermints and her own homemade applesauce.

After the war, Capi sold the Caprice (it was promptly destroyed by fire) and replaced it with a clinker-built runabout that didn’t see much use. She did some foreign travel—in 1952 she subjected herself to a gruelling trip across Mexico by rustic local bus—and in 1957 she flew to England to visit Betty. While there she bought a Land Rover and toured England and parts of Europe, joined some of the time by Betty and her two children. After that she hunkered down at Clovelly, receiving occasional visits from family and putting finishing touches on her masterpiece.

This is a glimpse of what our grandmother was like. All who spoke of her mentioned how very private she was, and we’re not sure anyone could say they knew her well. She would have presented herself one way as a mother, another to fellow adult boaters, friends and neighbours and yet another side as a grandmother. She was a unique and talented person and we count it as our good fortune to have spent time with her.

Michael Blanchet and Judy Reid, 2024