A Whale . . . Named Henry

The Coast Pilot at times either terrifies us or else gets us into trouble. Quite naturally, I suppose; for they have big vessels in mind—and what does or doesn’t do for a big vessel isn’t always right for the little boat. That is where the local inhabitants are a help. One of them says to us: “Oh, you don’t have to do that—you can take a short cut. See that island? Follow it down until you come to the old sawmill. Then line the sawmill up with the three maples on the low point, about a mile down on the opposite shore. Follow t

hat line—and it will lead you through the reefs and kelp. After you reach the maples, it’s all clear. Save you about five miles, and you won’t have to wait for slack at the narrows.”

We follow instructions—it doesn’t look anything like a mill, but there are squared timbers on the ground and the remains of a roof. Then we look along the far shore, until off in the distance we spot the three maples. We steer across on the long angle . . . Someone shouts “Rocks!” but they are to one side and not on the line. If we follow instructions and don’t question them, we never get into trouble in using the local short cuts.

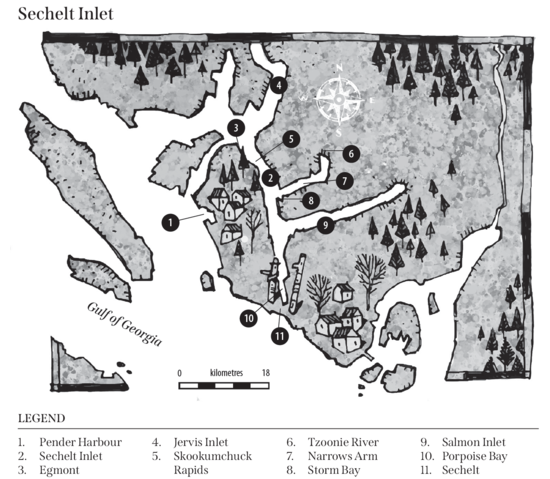

The Coast Pilot, speaking of Sechelt Inlet, says: “Three miles within its entrance, it contracts to a breadth of less than one-third of a mile, and is partially choked with rocks and small islands which prevent in great measure the free ingress and egress of the tide, causing the most furious and dangerous rapids, the roar of which can be heard for several miles.” These rapids, whose maximum velocity is from ten to twelve knots, “prevent any boat from entering the inlet except for very short periods at slack water.” Then it adds that “It would be hazardous for any boat, except a very small one, to enter at any time.”

Well, we were a very small boat, thoroughly terrified by the Pilot book, and we were creeping cautiously along on the far side—listening for the roar. When we heard it, we supposed that we should have to wait for it to stop, and then we would get through.

“Just like Henry,” breathed Peter and John, all excited. Someone, three or four years ago, had told me a true story about a blackfish or killer whale that had gone through Skookumchuck Rapids into the inlet, and couldn’t find his way out again. He was evidently in there for a couple of years. All the tugboat men knew him. When they tooted their whistles the whale always appeared, hoping they would show him the way out.

Only last winter Peter and John and I had been sitting in front of the big fireplace trying to think of a book to read aloud. Books to read aloud are much harder to find than just books to read. Finally, I suggested that if the three of us put our heads together, we should be able to write one for ourselves. Peter and John took this literally and their heads came bang—against mine. Peter shouted, “Contact!” and John said, “Sparks!” and up came, of all things, a blackfish.

I sat there holding my head. What on earth had made me think of a blackfish, which is just a local name for a killer whale? The only one I had ever given a second thought to was of course the one that had gone through the Skookumchuck and couldn’t find his way out again—it always rather intrigued me. But who would ever try to write a story about a whale!

I had to stop thinking. Peter kept asking, “What have you got?” And John, very eagerly, “What did you see?” and I was feeling more and more reluctant to tell them. I finally suggested that we try it again, just to make sure, and then I would tell them.

“Well, we’ll do it harder this time,” warned Peter. And they did.

“Contact!” cried Peter, expectantly.

“Sparks!” said John, in a very deep voice, as though he thought the stronger the sparks, the better the results.

And there again—only worse—much more definite. In words—“Up the coast there lived a whale—named Henry.”

So, in despair, I had to tell them. There was a pause, and John, always ready to make the best of a thing like that, cried excitedly, “And he could be sick and throw up ‘amber-grease’ and we could find it!”

And Peter said scornfully, “Don’t be silly, he wouldn’t do that. And anyway, this is to be a story, and he’s going to have a’ventures.”

Peter and John finally went to bed, and I sat there alone—perfectly miserable, with a whale—named Henry—on my hands. I thought of trying to get rid of him, but it was too late for that—I even knew what he looked like. Beyond that I knew nothing; and I stuck at that point for ages. Then, one night, when there was still nothing to read, John started to cry . . . “Well, put the period at the end,” he sobbed; “that will be something anyway.”

So, for some time, there was a big, round, black period, patiently waiting on the last page—and John felt a little happier. I had never even been in Sechelt Inlet—but with the aid of a chart, the Coast Pilot, and a good deal of imagination, Henry finally reached the big black period—and the tale was ended.

And this was the story of Henry, the Whale . . .

“Phuph . . . e . . . e . . . w!” blew Henry in disgust as he just missed a salmon that sprang out of his way.

“Phuph . . . e . . . e . . . w!” blew Henry in alarm when he tried to swim back the way he had come. He didn’t seem to be making any headway at all. Henry tried again and again but a whirlpool sprang at him and spun him round and round. Then it sucked him down . . . down . . . round . . . faster and faster. Then up he was thrown to the surface and he blew out his breath with a roar.

The Skookumchuck rapids tossed him out on to a jagged point of rock and the strong waters pulled and tore at him. They tossed him along and then threw him up into the quiet inland arm of the sea. He lay bruised and bleeding.

A salmon rose out of the water and seeing him darted away in fright. He swam up and down the bays and inlets spreading fear among the other fish telling them about the big killer whale in the arm.

“What!” shrieked a seal who was about to make a meal of the salmon but closed his mouth in time. “A whale in the inlet? How terrible!”

Henry lay motionless in a great bed of kelp—thirty feet of black and white misery. He lay for three days without stirring. Just when the crab and the rock cod who lived there were working on how long one whale, thirty feet by eight feet, by six feet would live—Henry moved his tail. Not very much, but he could feel it all the way up to his head.

“Oooooooh!” he groaned.

Everything in the kelp bed scuttled for their lives except the crab—who had done the most work on the problem and waited to see what the answer would be. However, Henry moved his tail again and it wasn’t quite so bad this time. He tried moving his eyes next and found that he could still see. He tried thinking. What had happened? Then he suddenly felt very guilty remembering his mother saying over and over, “Keep away from the Skookumchuck rapids. If you ever have to go in, wait for slack tide to come out again.” Henry remembered it all now but he had been diving and rolling along the inlet when a great school of salmon had suddenly appeared. He was so excited that he had followed them, forgetting everything else (and not even noticing that they were heading for the Skookumchuck). Henry groaned again and the crab looked expectant.

The next day Henry felt so much better he decided he would look for the way out. When he began moving about he realized he was quite hungry. In a couple of great gulps Henry swallowed all the inhabitants around him—including the crab whose arithmetic didn’t interest him at all.

“That feels better!” sighed Henry and away he swam. But no matter which way he turned he bumped into a cliff. “This is getting tiresome. I’ll have to ask somebody.”

Henry spied a seal, but the seal saw him first and swam off in a flurry.

“Hi there,” he called seeing a school of salmon. But they leapt out of the water and continued leaping until they were out of sight. “Nasty rude things!” Growling and grumbling to himself Henry sank into the depths to try and think what to do next.

“Well,” yawned a voice from somewhere, “If you have rested long enough I wish you would get off my rock, I want to catch my supper.”

Henry’s jaw dropped. The voice sounded as much under him as any place else. He raised himself slightly and tried to look underneath—but it was very hard to see. “Where are you anyway?”

“Right here on the rock beside you,” said the voice.

“I don’t know what you are and I still can’t see you.”

“Look harder,” chuckled the voice. Henry stared and stared. Then right there on the rock, where Henry was sure it wasn’t, was a large red octopus with its long arm coiled about itself. As Henry stared it slowly faded out of sight again.

“What do you think of that?” asked the voice.

“Stupid,” said Henry crossly. Then from nothing came a cloud of dirty black water and something reached out and pulled his nose.

“You horrid miserable jellyfish,” raged Henry swishing his tail around and flattening everything. “I’ll squash you for that.”

He banged down on the rock and stayed there, wondering if you could eat what you couldn’t see—and what it would taste like if you could. A school of rock cod came swimming by and goggled at a stone-grey octopus arm waving at them from a crack in the rock upon which Henry was sitting so hopefully. They giggled nervously and Henry said, “Hush! I’ve just squashed an octopus and I’m listening.” The cod rushed off in a frenzy at the idea of an octopus teasing a thirty-foot whale.

Henry began to tire of sitting on what he could neither see nor feel and he just had to get up for more air, so he gave an especially hard squash and shot to the surface. Then he remembered suddenly that he had gone down there in the first place to think. Seeing a rocky island ahead he eyed it with satisfaction. “Just the place for a think,” he said.

After a good long think Henry decided that the best way to find the way out was to look for the roar first. Then he would know he was at the Skookumchuck and when the roar stopped and he could see the green stain on the white rock the tide would be slack and he would swim through. Simple. Henry was very pleased with himself.

“Now,” said Henry, “All I have to do is to swim along the surface until I hear the roar. If I keep the cliffs on my left side I won’t get confused.” Every cliff Henry rounded he would listen carefully. It grew dark and still Henry swam on. The cliffs grew dark and tall and Henry swam on watching the stars. A cold grey light began to spread over everything. Seagulls looked pale against the silvery light. Henry could make out a deep bay just ahead of him and decided that it would make a good place for breakfast. The whole bay tossed and heaved with commotion and Henry’s cavernous mouth devoured everything in sight.

As Henry swam out of the bay he saw a white goat come down on a point of land. It stood there and made the kind of noises goats make. Henry stared. This was something new. The goat came down to look at Henry who was new to him too. Whatever it was the goat decided, Henry would be company, and he jumped and hopped over the rocks alongside of him. Whenever Henry stopped the goat would stop, his head, with its ridiculous beard, tilted to one side. Henry decided he didn’t like it and tried blowing at it. But that seemed a waste of time as the goat seemed to enjoy it.

“I’ll race and leave it behind,” decided Henry. So away he tore with the goat following and soon left it behind. Henry raced on. Then suddenly—oh no, not another one! This time Henry wasn’t waiting to see if it would follow but tore past it at full speed. The goat had time only to turn his head as Henry raced by. Every mile or so was a narrow channel and great frowning heights and then—another goat . . . ! They were getting as thick as minnows. Henry put on an extra spurt.

Another goat! Henry blinked. Something was wrong. He was beginning to feel quite queer. Henry stopped with a lurch and the whole world with the goat standing on top went round and round and round. Henry felt very sick.

An angry kingfisher bird spluttered at him from a dead branch. “Look here, what are you racing around and around our island for?”

Henry stared. “Island?”

“Yes island. You’ve been around it half a dozen times now and it’s becoming quite upsetting.”

“Oh dear,” sighed Henry, “I shall have to start all over again.” Evening came calm and cool and peaceful and Henry settled down to a steady roll. Suddenly right in his path he met Timothy. Timothy opened his mouth and squawked at him. He was a very young seagull and “Squaaaawk,” said Timothy again more insistently.

Henry was so astonished that he could only stare. Things—especially small things—didn’t usually squawk at him. Then as he stared, Timothy opened his mouth again and held it open—quite plainly telling him that he expected Henry to fill it.

This really was embarrassing. How could a whale feed a bird? Timothy looked at him with bright and fearless eyes. Henry wiggled his tail.

“Look here,” he protested. “What’s the matter with you—don’t you realize what I am? Why aren’t you flying anyway?”

“Can’t,” answered Timothy, “I have a broken wing.”

Henry looked. One soft grey wing had been broken just above the second joint. “A man mended it for me but it’s still not good.” It had been carefully set with three matches and bound with a piece of fishing twine.

“Hmmm,” said Henry trying to think of something to distract the bird so it would forget about being hungry. “What’s your name?”

“The man that fixed my wing called me Timothy.”

“Timothy! Why did he call you that?”

“Because my toes are pink.”

“Oh,” said Henry, eyeing him nervously, and Timothy opened his mouth wide and squawked.

“I—I say,” protested Henry desperately, “I haven’t got anything to eat and I wouldn’t know how to feed you if I had.”

“Couldn’t you catch me even one little fish?” pleaded Timothy.

And that is where Henry made his first mistake. He said alright rather ungraciously and then dived and presently appeared with a nice grilse in his mouth which he put in front of Timothy and hastily backed away. Timothy was quite capable of eating it himself and when he had finished and had rinsed his beak and ruffled his feathers as well as he could with the broken wing, he turned confidently to Henry and asked, “Well, what shall we do now?”

That was when Henry made his second mistake. He stammered, “Whaaat?” He tried to mend matters when the seagull repeated the question by saying he couldn’t do anything as he was looking for a way out.

“Way out of what?” asked the seagull.

“The way out of this inlet, of course,” said Henry gloomily. “Why I’ve often been out of here,” said Timothy. Henry turned and stared at him. “Often been out,” repeated the seagull, nodding his head, “Often, often.”

“And you’ll show me?” asked Henry eagerly.

Timothy said he would but tomorrow, not tonight as he was sleepy and without even bothering to say goodnight, tucked his head under his good wing and went to sleep bobbing gently on the water.

Henry was left wondering if it were safe to trust a seagull who was called Timothy because his feet were pink but since there was nothing he could do about it anyway he decided that he would go to sleep too.

It was quite light when Henry woke up the next morning—or rather was wakened up. “Squaaawk,” said a voice suddenly in his ear. Then he remembered.

“I wish you wouldn’t do that before I’m awake,” grumbled Henry.

But Timothy wasn’t intimidated and just opened his mouth wider. Henry knew what was expected of him and grumpily told Timothy to stay where he was and dove out of sight. It took some time to find Timothy’s breakfast since he decided to eat his own while he was down there. It takes a lot to fill up a killer whale. Finally Henry felt satisfied and seeing a small grilse he said, “Just the thing for Timothy,” and took it carefully in his teeth.

He exploded through the surface but there was no sign of one small seagull. He was afraid he had come rather a long way. He tried calling the bird but it didn’t come out very well with the fish in his teeth. He tried blowing hoping that might attract his attention but he couldn’t give a decent blow either. “Timothy,” he called and out shot the grilse. Before the last echo of Henry’s shout died away the little fish was safely hidden at the bottom of the sea.

“Now he’s made me lose his breakfast,” grumbled Henry irritably looking all about him. “Perhaps I’ve swallowed him,” he thought hopefully and gulped a couple of times to see if he could feel anything half way up or half way down.

“Squaaawk,” said a voice right beside him. Henry wheeled and there was Timothy sitting with his mouth open and eyes shut.

When Henry had replaced the bird’s breakfast and he had rinsed off his beak he said, “Well, come along and I’ll show you the way out now.”

It wasn’t long before Timothy was exhausted, paddling along trying to keep up with Henry. “You’ll have to give me a ride.”

“Ride,” exclaimed Henry. This was an indignity to end all indignities. Pat-pat-pat, cold pink toes pattered up his back accompanied by much squawking and fluttering, for Henry was very slippery.

Henry gave a cautious roll forward and Timothy slid squawking down his back. Just as he reached Henry’s blow-hole Henry let out his breath and up shot Timothy into the air.

“Beast,” spluttered the bird as he flopped into the water with a splash.

“Sorry,” said Henry cheerfully, “It wasn’t my fault.”

“Of course it was your fault. Who ever heard of anyone having waterfalls in the top of their head anyway?”

“You’d better swim then,” said Henry.

“I won’t,” said Timothy.

“Well don’t. I’ll find my own way out.” Henry blew savagely and decided to teach Timothy a lesson and tore round and round making huge waves. Up and down bobbed Timothy not making a peep.

“Alright,” shouted Henry, “You can ride.”

Timothy decided to try behind Henry’s big fin this time and so long as he rolled gently the seagull was able to stay on. Presently Henry felt that something was not right. It was dark now but Henry could feel that the water was getting shallow and still no sign of the way out. He was just about to say as much when there were excited squawks from Timothy.

“I can see it. I can see it. Straight ahead.”

Henry went forward cautiously trying to see in the darkness, but as far as he could see, trees loomed in an unbroken circle against a quiet sky. What was worse, the water was getting shallower and shallower. Then he felt weeds tickling his tummy. “What are you stopping for,” shrieked Timothy stamping his cold pink toes.

“Because there isn’t enough water,” said Henry darkly.

“That doesn’t matter, its only fifty yards across here and then we are right out in the open water.”

“Fifty yards of what?”

“Sand,” shrieked Timothy. “Nice soft sand.”

So that’s what soft pink toes led to—nice soft sand. He might have known. “Get off my back,” thundered Henry and Timothy got off. “Now go on.”

Timothy started off obediently but looking back over his shoulder in a bewildered way he asked, “But aren’t you coming too?”

“I—can’t—swim—in—sand!”

“Oh.” And in the darkness Timothy heard a big watery sob, “Shall we try again,” he said in a little wee voice.

Gently Henry backed out of the shallow water. In the dark he turned slowly around and moved ahead. Dark outlines of cliffs drifted past and then suddenly they seemed right on top of them. Henry raised himself out of the water to look. Along the shore the water was making soft gurgling noises, climbing up the stones as far as it could reach, then suck-suck, as it drew back again. Against Henry’s sides it rippled, lip-lip-lip. Hurry, hurry, lapped the impatient ripples. Gurgle, gurgle, said the little eddies. Hurry, hurry, louder and louder, faster and faster. Henry lay there wondering and thinking. Then everything kept getting louder and louder and stronger and more insistent.

“It’s certainly making enough noise,” he was thinking, “roaring like anything. Roaring!” he jumped. Of course it was roaring. “Timothy,” he bellowed, “jump off. It’s the Skookumchuck and I have to hurry while the tide is slack. If you stay on you will get drowned. I’ve found it. I’ve found the way out. Jump off. Goodbye. I’ll see you on the other side.”

Poor Timothy was quite shaken up but he jumped and paddled to the shore by the light of the moon. He watched Henry move ahead through the whirlpools and ripples that were gentled now.

Henry could feel the roaring waters close behind on his tail. Suddenly he saw the Indian village and he knew he was out and safe.

“Out,” he shouted, “Why I’m out! Out, out!”

A little voice back on shore echoed, “Out, out. Henry’s out. Ha, ha. Henry’s out.”

It was after that that we decided to go into the inlet ourselves, and see all the places and things that Henry had. So now, just like Henry, we were trying to find the roar. Suddenly, we heard it—and then we saw the water boiling out from behind the farthest island: The Indian name “Skookumchuck” means “Strong Waters.’’ How smoothly the translation flows, and how the Indian name boils, swirls and roars! We hastily tied up to a private float against the shore. I should have liked to ask some of the local people about it—before we tried it, even at slack. But the house on the hill was empty, and no boat lay at the wharf.

We ate our lunch while waiting for the roar to stop. We had just finished, when ahead of us, on our side, we could hear the whine of an approaching outboard engine. The sea there seemed completely choked with kelp and small islands, but out from behind an island came a rowboat with an outboard and one man—without a doubt, a local inhabitant. No one else could have wound through that kelp with his sure feeling. Then into the open he came—straight our way—and tied up at the float.

We were round him in an instant, asking questions. He first asked how much our boat drew. Then told us that we could get through where he had come, at any time and any tide. There was a passage through the kelp, about eight feet wide and four feet deep. We couldn’t mistake it—it showed clearly when you got closer. It led right through into the inlet, and nowhere near the rapids.

“But we’ve got to go through the rapids,” broke in John, “because Henry did.”

“Who is Henry?” the man asked him.

“Henry was a whale,” Peter answered. “He went in there, and he couldn’t find his way out again.”

The man laughed. “I knew that whale, young fellows, but I never thought to ask him what his name was.”

We thanked the man, and took off for the kelp-bed—where the ribbon of kelp-free water showed perfectly clearly, just as he had said. Across on the other side the Skookumchuck was still roaring furiously and dangerously—while we slipped in easily through the back entrance. Peter and John were still glooming, because we hadn’t gone through where Henry did.

I think it is a mistake to go back to revisit places you have known as a child. They are all changed and shrunken—and you feel lost and lonely. And, I was beginning to suspect—also a mistake to visit a place you knew only from a book. Peter and John were expecting to find this inlet just as they had imagined it—which came to them second hand from what I had imagined. So each of us was going to be disappointed in his own way. A couple of years ago I discovered that Peter thought the government was three men sitting on a green bench. He preferred his version to anything I told him—probably still does for all I know.

I got out the chart and gave Jan the wheel . . . “Keep to the left, close along the cliff,” I said.

“Why?” she asked, as she turned in closer.

“Jan!” said Peter; “don’t you know that Henry always stuck to his left cliff?”

“There’s the little island where he stopped to think,” I pointed out. The island satisfied all of us—just about what we had all imagined it to be like. There were the twisted juniper at the edge, the stunted pines on the crest, the moss and stone crop above the high water mark. As Henry said, “Just the place for a think.”

One woman editor I sent the story to wrote back to say that “All children don’t like personalized animals”—that she herself found it hard to come to grips with Henry.

She was quite mistaken—it was the other way round. I had always imagined that I was inside Henry. Now that I was in the inlet I found that I was looking at it entirely from Henry’s point of view. If an editor can’t get inside a whale, if called upon—it’s her own loss—she doesn’t have to put it off on the children. Children can imagine anything, and come to grips with it. They have no difficulty whatever in getting inside frogs, rabbits, ducks or anything else—they just take a whale in their stride.

We turned into Narrows Arm, still keeping the cliffs on our left. We could go very close, for there were thirty-five fathoms right off the sheer drop of the cliff. Then the two sides of the arm squeezed together until the cliffs were only about two hundred feet apart. Five-thousand-foot mountains on either side made it seem much narrower. Quite a strong current was swirling through and rushing us along. No wonder Henry thought he had found the way out at this point.

The chart showed the end of the inlet as merging into the Tzoonie River, with four outlets. So I had surmised that it would be shallow with mud flats, and enough fresh water to have a lot of dead jellyfish around—and that was just what we found.

Seagulls were wheeling overhead and screaming at our intrusion. There were lovely, sheer cliffs going up and up and up, in terraces, to over six thousand feet. But boats, like whales, have to think of the water under them. This would be no place to spend the night in—what with mud flats, and the mosquitoes and no-see-ums that the low land behind would breed. So we just took a turn round, with Jan sitting astride the bow as lookout, and got out again as fast as we could . . . and the seagulls jeered and laughed, and settled down on the water again.

There was a little island in the bay just past the narrows—through which we had to fight our way against the current. But the island was steep-to and there was no anchorage. Anyway, we really wanted to spend the night in Storm Bay—where Henry had dropped in for breakfast. So we ate some hardtack and settled for another two hours.

Storm Bay was not really a very good place to spend the night. It was completely open to the west. The wind that blew down Jervis Inlet in the late afternoon and evening was perfectly likely to follow the mountains on into Sechelt Inlet. We had not been in there before, so we didn’t know what to expect. There were two little islands just inside the entrance to the bay. By putting out a stem anchor, I strung the boat in between and hoped for a quiet night.

The day had been hot, but now the sun had sunk behind the mountains to the northwest and the air was just pleasantly warm. Slowly the lower hills were taking on that violet hue that would deepen into purple at a later hour.

Dinner over, and the bunks made up, we rowed slowly into the end of the bay. From the cool, dark woods behind, the thrushes called and called with their ringing mounting notes. Back of the beach we found a wooden tub that some fisherman or trapper had sunk into the bank to catch a stream of water trickling over the rock and through the ferns. I leant over and shaded my eyes to see if I could see the bottom of the tub. There on the bottom was a little brown lizard . . . The lizard, and the water smelling of wet barrel staves, moss and balsam, sent me hurtling back through the years—to a similar though larger barrel, on the cliff path on the way down to the beach at Cacouna, on the lower St. Lawrence below Quebec. There, you had to raise yourself on tiptoes on the wet slippery stones, to drink deep of the cold water that welled over the edge of the barrel . . . Exactly the same smell to the water—wet wood, moss and fern and balsam. And if you shaded your eyes and looked down at the bottom you almost always saw a little lizard—just like the one at the bottom of this tub in Storm Bay—thousands of miles away.

I told the children about the other barrel, when I was a little girl—so they had to smell the water too, and look at the lizard. John was fascinated by the idea that I could ever have been as little as they were . . .

“Some day, when you are big, you will find another barrel with a smell like this—and a lizard—and it will bring you right back to Storm Bay,” I told them.

Down at Cacouna, as here—the thrushes in the cool woods called and called. Down there, there was another variety as well, that rang down and down—dropping, dropping . . .

On Sunday mornings, all through the church service in the little white church in the middle of the pine woods—a little church that smelt of scrubbed pine and had hard pine benches to sit on, but little red carpet pads to kneel on—all through the service I listened to the thrushes ringing up—mounting and mounting . . . ringing down . . . dropping and dropping . . . and never heard the service at all.

The water in the bay was quite warm. When it got dark we went in swimming off the boat, so that we could make flying angels. When the water is full of plankton, if you lie on your back and float, and move your arms through the water—first down to your sides, and then up against your head—you make great shining wings.

I climbed back on board with John to watch the other two. Jan started taking big mouthfuls of water and spouting them up in the air—liquid fire that broke and shattered in the air, and fell and splashed. Peter tried it too, but he laughed so much that I had to haul him on board and thump his back—then subdue him with towels.

I finally threatened to pull up the ladder if Jan didn’t come out. “I don’t care if you do,” she said. “I’d like to stay in all night.”

Just then a heron let off a shattering “Caaawk” as it swerved over our heads. That was too much for our angel of the spouts, and she climbed up the ladder in a hurry—all wet and shivering.

It was quiet all night. I woke at times to check. Any bay open to a prevailing wind is always an uneasy anchorage. The constellations were slowly wheeling round the Pole star. They had almost made a semi-circle, the last time I woke—and grey light was showing in the east. Then I pulled my sleeping bag over my head, and really slept.

I was wakened by Peter and John arguing whether there had been any fish left in the bay at all—after Henry dropped in for breakfast. I shoo’d them off in the rowboat to look for some, while I had a swim. Even breakfast didn’t stop the argument. I pulled the chart out and showed them the island where Henry had found the goat.

“Will the goat still be there?” they demanded.

“Probably,” I foolishly said.

Darn Henry anyway! Why on earth had I said that the goat would probably still be there? Peter had the binoculars and was watching the island—and John fought him for them every time Peter took his eyes from them.

I slowed down a little . . . no use hurrying to meet trouble. Who ever heard of a goat on an island, miles from anywhere—please, oh please, let there be a goat . . .

“I see it!” shrieked Peter, pointing. I grabbed the glasses from him. There, on the point, was a white goat waiting for us.

I sat down. I felt exactly like Saint Theresa—all weak in the knees. Challenged by a guard when she was smuggling forbidden food to starving prisoners, and asked what she had in her basket—“Roses,” she said. He pulled off the cloth that covered the basket—and it was full of roses.

That silly goat! It was a wonder we ever got any farther at all that day. It did all the silly things that goats do; and said all the silly things that goats say; and stuck to the children like a leech. It was a young billy, and must have been brought up with children. When they came on board to lunch, it stood on the point, bawling . . .

It was in the middle of the afternoon when, tired of feeling eternally grateful, I tooted my little whistle and started pulling up the anchor. The youngsters did their best to get back quickly—realizing that my patience was at an end—but the goat jumped into the dinghy too, and they couldn’t get him out.

“What will we do?” they wailed, desperate eyes on the anchor. I gave some advice, as well as I could for laughing, and they went on shore again. The goat of course followed. They picked a pile of green leaves for it, and Jan sat beside it while Peter and John got in the dinghy and pushed off a little way. Then, when the goat had a mouthful of green leaves, Jan got a head start—giving a mighty push as she jumped in. Peter pulled on the oars and they were safe. But how that goat bawled, and how the children worried about it!

“How would you like to be a goat, all alone on an island?” demanded Peter. But he didn’t take up my offer to leave him behind to keep the goat company. It is bad enough, sometimes, to be cruising with a boat full of children without being pestered with stray characters out of a book.

It is ten miles from Goat Island up to the end of Salmon Arm, which runs off to the northeast from Sechelt Inlet. We fished for our supper on the way, and caught a five-pound salmon—which relieved the tension caused by the lonely goat. Late in the afternoon we made our way slowly alongside the cliff where Henry had waited for so long. Peter and John showed very little interest—they were still discussing the goat. It was I, in spite of myself, who kept looking for the white vein of quartz and the green copper stain—by which Henry had gauged the rise and fall of the tide while he was waiting for the roar of the falls to stop—thinking it was the roar of the Skookumchuck, and the way out. And it was I who kept expecting, and was disappointed not to find, the old Indian village by the falls—“Old-village-by-the-water-that-never-stops.”

The end of the arm was not quite as I had expected. I had thought there would be one large, roaring waterfall. It roared all right, but at this season there were three smaller ones, spilling over a wide sweep of smooth sandstone terraces. There were the remains of an old shingle mill, and the flume that had carried water down to turn a generator. Big logs stranded on the sandstone slopes showed what a tremendous volume of water must come over the falls at times. We climbed up the dry sandstone and to our surprise found a large lake—the chart had just shown an unexplored blank.

In the morning we rowed across to the other side of the bay, where we could see a small float held out from the cliff by poles. There was a steep trail leading up through the woods, and high up at the lake level we found a small cabin and an elderly man and his wife. They were caretakers for some fishing club—which kept the lakes stocked with trout—fishing for members only. There were two lakes, the second one much bigger than the first. He said he had an old boat tied up on the lake. We could use it if we would like to row up to the next lake and swim.

We rowed up as far as the second lake, which was about three or four miles long and a mile wide. The two lakes lay in a deep cleft between very high mountains, and must have collected all the drainage from their slopes. The boat was too old and waterlogged to row very far.

We drifted along in the shade of the trees, and watched the trout rising to some kind of fly that kept dancing just above the water. I had stooped down to bail the boat again, when I spied a sealed glass jar underneath the “back seat.” I picked it up—it was bottled salmon-eggs! Illegal! That old caretaker! What would the f ishing club think of that! What did we have on us that we could be illegal with, too? Peter produced a piece of minnow line from his pocket. Jan had a very small safety pin, and I had a lucky ten cent piece with a hole in it. And John, who at first thought he had nothing at all—cut a stick for us.

The ten cent piece made a good lure, although it twisted the line up a bit. An unripe huckleberry looked like a salmon-egg and was not nearly as smelly as those under the seat. We found that you had to have a very quick technique or else these ten-inch trout either bent the pin or slipped off it.

We stopped at four fish. Then wrapped them in cool green fern. When we got back to the landing, I sent the youngsters back by the sandstone terraces with the fish—while I went back by the cabin to thank them for the boat.

“I could have lent you a line,” he said, “and you could have caught yourselves a mess of trout. We hardly ever see anyone up here, except the members.”

How much more fun we had pirating them!

I insisted on hugging the left cliff on the way out too—although the children insisted that Henry hadn’t. He hadn’t—he had finished with cliffs for life when he found they had only led him to the roar of the falls, instead of to the way out. But this left cliff was two miles distant from the island with the goat. I might, or might not be finished with goats—roses were easier.

So we hugged the left cliff, and that led us into Porpoise Bay, where Sechelt Inlet is separated from the Gulf of Georgia by only fifty yards of nice, soft sand. That was where Timothy, the young grey seagull, had taken Henry to show him the way out.

In the garden at home there is a little grave—with a gravestone. On it is laboriously carved, “Here lies Timothy—dead.” It was supposed to say “dead of a broken wing,” but there wasn’t room, and the stone had been very hard. We had found him in the garden one day—very bright eyes looking at us out of a clump of long grass. He had a broken wing, which someone had evidently tried to fix with a couple of matches and a piece of fishing twine. We tried to fix it again, but he always pecked it off. We called him Timothy, because his toes were pink. But he wouldn’t eat, and after a week—though surrounded by much love—he died. So they had a sorrowful funeral for him—and Peter carved his stone. That was last fall—and Timothy had just naturally wandered into the story of Henry.

Porpoise Bay was very shallow as you got in farther, and the weeds tickled the bottom of the boat, just as they had tickled Henry’s tummy. It was too shallow at that stage of the tide to get into the float; but the children landed and raced across the fifty yards of nice soft sand, to look at the Gulf of Georgia.

I sat in the boat, looking at the nice soft sand. That was where Timothy had stood, his broken wing trailing, looking over his shoulder in a bewildered kind of way, asking, “Henry aren’t you coming too?”

“Poor Timothy,” said John, in his very saddest voice, as he climbed on board. “It was quite a long way, with a broken wing.”

“I carved that gravestone, you know, John,” said Peter.

“I know,” said John, “but he wasn’t only yours.”

“Most of it was just a story,” said Jan, firmly, as she sat down astride the bow. “And Mummy wrote it.”

“I know,” said Peter. “But we all helped; I said ‘Contact,’ you remember.”

“And I said ‘Sparks,’” reminded John.

Bumping heads together may be a good way to produce unusual characters—but not if you ever want to get rid of them again.