Fog on the Mountain

I suppose it is the confined quarters of a boat and the usually limited amount of standing room on shore that makes the idea of walking or climbing so enticing. Which, being so enticing, makes one completely forget that the same cramped quarters are hardly good training for mountain climbing.

John, for two or three years, was a complete ball and chain. I suppose I must have walked miles with him astride my hip, on more or less level trails. It was the time in between—when he was too heavy for my hip, but not big enough to attempt the longer hikes or climbs, that we were most tied to the beach.

One September we bribed John to stay behind at sea level with some friends, and five of us set off to climb six or seven thousand feet up behind Louisa Inlet. We planned to stay on top over one night, so each of us had to carry a blanket or sleeping bag, plus a share of the provisions. The last we cut to a minimum—tea, as being lighter than coffee; rye-tack lighter than bread; beans, cheese, peanut butter—the least for the most. Even then, halfway up we would all have gladly slept without blankets and starved until we got back. A pack certainly takes the joy and spring out of climbing.

A mile, I believe, is 5,280 feet. If you climb 5,280 feet you are not going to be on top of a mountain of that height.

Our first point was a small trapper’s cabin at 600 feet. It was at the end of a skid-road that sloped up fairly gradually from sea level. I am sure that it was nine times 600 feet before we sank panting beside the cabin, and it seemed breathlessly hot there, in the middle of the tall trees. We drank from a running stream, we bathed our faces and arms in it, and bathed our feet in it while we emptied the earth and gravel out of our running shoes. “Doc,” who led the party because he knew the way to the top and had carried by far the heaviest pack, sat there deploring the idea of our waterlogging ourselves. The man off a yacht, who had come to go half-way with us to take pictures, spoke longingly of lunch. But Doc pointed out that lunchtime and the half-way mark was not until we reached the cliff where the black huckleberry patch was. That we knew perfectly well. We had all been as far as the huckleberry patch—but never with packs on our backs.

We made fresh blazes on some of the trees as we moved on—double blazes at some of the turns. The man off the yacht was going back by himself, and it was not good country to be lost in.

At long last—at 4,000 feet—we climbed the “chimney” and sank exhausted beside the huckleberry patch. We boiled a billy for tea, and ate the sandwiches that the yachtsmen had carried for the first meal. There were not many huckleberries left. A little late in the season, but I thought, judging by the broken branches, that the bears had been feeding on them.

Doc warned the man off the yacht against attempting any short cuts on the way back, there just were none. Then we shouldered our packs, said good-bye to him, and started climbing.

Doc had been up once before, so knew the general direction we had to take. He was looking out for a diagonal stretch of red granite—an intrusion in the midst of the grey granite. If we could find it—and we had to find it—it would lead us up the next two thousand feet. After some false starts, and having to retrace our steps, we spotted a cairn of stones. Doc identified it as the place where we had to begin angling up towards the beginning of what he called “Hasting Street.” We could see that if we didn’t angle we would get involved with cliffs ahead. Once on Hasting Street we would start angling back in the opposite direction.

It was time for another cup of tea before we finally came out on Hasting Street. We had spent the last couple of hours scrambling up and down and over . . . and up again. Cliffs above us and cliffs not far below us. Then suddenly, in the midst of the tall mountains, we came out on an almost civilized highway—a strip of smooth red granite stretching up at a forty-five degree angle. It was perhaps thirty feet wide, with a gutter of running water over on the left side. The road itself was smooth and dry, with no obstructions. It was the uniformity of its width that was its most arresting feature—after you recovered from the shock of its being there at all.

We drank from the gutter, we bathed our tired feet, we lay down on the hot rock in the sun . . . All but Peter, who ran up and down, sailed scraps of paper in the gutter, and raced down the smooth granite to intercept them below. The resiliency of small boys always astonishes me—they are either awake and in constant motion or else asleep and unconscious—nothing in between.

The Doc looked at his watch, and remarked that it was still a long way from the top—and it was now almost five o’clock. Far down below, the sun would have left the little inlet. But up here it still shone on our bent backs, and a blast of hot air came up from the rock as we toiled along. The calves of our legs stretched and stretched . . . the soles of our running shoes got hotter and hotter—and we could feel the skin on the soles of our feet cracking and curling. We would stop for any excuse at all . . . and then trudge, trudge again . . . Doc started zigzagging, and we all followed. That cut the angle in half, but lengthened the distance. However, it did help our laboured breathing.

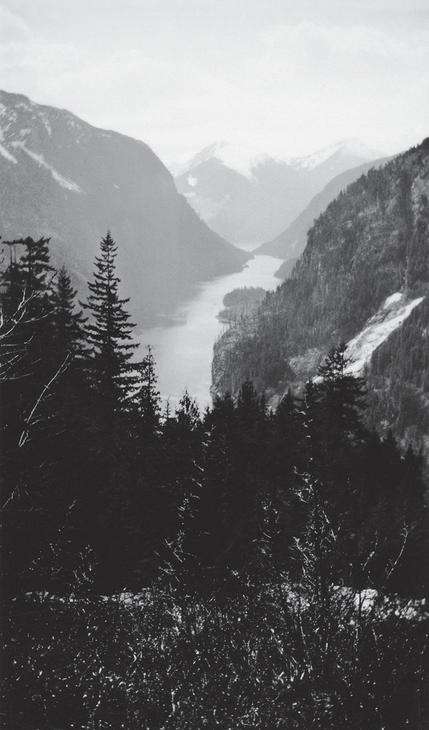

Then the peaks of the mountains came into sight ahead of us . . . then the snow-filled gullies . . . and our tiredness was forgotten. Towards the west, as far as we could see, there was one vast expanse of snow, dotted with snowy peaks poking through. We were level with it all, and couldn’t see the valleys and ravines that must cut down between the peaks. It was easy to imagine putting on skis and gliding across the snowfield the whole way to Desolation Sound. But we knew that quite close on that snowfield it was possible to step off the mile-high cliff and fall straight down to the inlet below. We knew that, if we followed the ridge we were now standing on to the southeast, it would lead us over to Potato Valley and on down in the Queens Reach of Jervis Inlet. A prospector had told us of trips he had had up on the ridges that skirted the ravines. There were mountain sheep that followed the ridges from valley to valley—hunting the green leaves and grass. And the grizzlies followed—hunting the sheep. He told us of one night, a couple of ridges over from where we were now, when he had barricaded himself in a cave, with his rifle across his knees—and two grizzlies had prowled outside all night, standing up and drumming on their huge chests, the way gorillas do. He hadn’t exactly enjoyed that night—then he put his hand in his pocket and pulled out samples of quartz flaked with gold, and pure white quartz crystals that they use in optical instruments—it was for these that he followed the ridges.

The peak above us, on which the summer sun shone all day, was dull, grey granite—but the snow lay about its feet like a slipped garment. Looking west, we were on the north side of all the dozens of peaks over towards Desolation Sound—and the sides towards us were fully clad in white, without any hope of ever melting. The autumn snow must already be falling on them at times.

We had a snowball battle but the snow was coarse and granular and didn’t hold together well. The sun left us suddenly, and we were cold and tired. Doc suggested that we find a place for the night and get some food inside us.

It took some time to find a place—among the moss in a more or less level place. We collected little twigs from some kind of scrub mountain plant, to try to get warm. But the twigs didn’t have any warmth in them. We were so thankful that Doc had insisted on adding a primus to his load. We heated a couple of tins of beans, and a billy of water for tea. Food made everyone feel warm again.

But a camp is not a camp without a fire. It was getting too dark and cold to do any exploring, so we decided to turn in at once and get up early to do our exploring, and take pictures when the sun first hit the opposite mountains. It would only take half a day to get back to the inlet.

Whatever made us think that one blanket each would keep us warm! Doc had the large eiderdown lining of a sleeping bag. It opened out full—and he and Peter decided to double up—Peter’s blanket under them, and the sleeping bag over them. The two girls found a hollow and filled it with moss—then curled up there together, under two blankets. I was left looking at my one blanket. None of us undressed—we put on all we had. But sweaters, shirts and shorts are not very much. Everybody except me seemed to settle down, and the deep breathing of unconsciousness soon rose from the smaller mound.

I got colder and colder . . . I couldn’t feel my feet at all. I made plans. I waited until heavier breathing from underneath the eiderdown sleeping bag indicated that Doc was finally off; then stealthily I crept closer. Cautiously I felt for the edge of the sleeping bag, listening . . . steady deep breathing from Doc. I could count on Peter not to waken—small boys never do. I pushed him over against Doc and crept in, dragging my blanket after me. Oh, the blessed warmth of Peter’s small hollow in the moss . . . the blessed heat of his small back! Nobody stirred—nobody dreamt that an iceberg had slipped in to spend the night.

I was wakened in the morning by something dripping on my face. I put a hand out cautiously, thinking that someone was playing a joke . . . but the whole sleeping bag was soaking wet. I opened my eyes—it was lightish, so it must be almost morning . . . but I couldn’t see a thing. We were engulfed in a thick, wet blanket of fog—on a mountain-top, a long way from home. Then I heard the sound of the primus being pumped, and I called out to Doc, who certainly wasn’t in the sleeping bag—and neither was Peter. Doc’s face appeared wreathed in white mist, looking wet and worried; Peter’s bursting with excitement—real adventure, lost on a mountain-top.

Doc, I could see, was really worried. Unless we could manage to find Hasting Street, we wouldn’t be able to get down off the mountain. We only had enough food for two meals, and no way of keeping warm. We drank the hot tea, warming our hands on the hot mugs, and scrunched a piece of rye-tack. Doc thought it would be better to pack up at once and start down, then eat later. We rolled up the dripping blankets and sleeping bag in long rolls and hung them round our shrinking necks.

Then, hand in hand, not daring to lose contact with each other, we inched along hoping we had come that way when we were looking for a camping spot. We couldn’t see a thing; there was nothing familiar underfoot. You could see the person whose hand you held—like some fellow spirit—but not the one beyond. I thought we were probably working too far to the right and towards the peaks—in our fear of bearing too far to the left and the cliffs. How slow were our uncertain feet; so reluctant, yet so eager!

Then, suddenly, out of the mist on the right, Jan called out, “Here is the snow!” and added a second after with a shout. “And here are our footprints!” Doc questioned us closely on whether any of us had walked in the snow after the snowball fight—nobody had, we were sure. Then he said that he knew now just about where Hasting Street was. We would have to risk bearing farther to the left or there would be a danger of passing it. Hanging tight to each other we strung along.

“Here it is, I think!” shouted Doc. We couldn’t see him, and his voice sounded all woolly and blanketed.

We crawled up to him and cautiously spread out in a line to the right. There it was . . . we thought. One end of the line searched for and found the gutter, and then we were sure.

We had ideas of a quick walk down the next two thousand feet of altitude in next to no time. Doc was the first to sit down with a bang before we had even started. Then my feet shot ahead of me, and I sat there jarred to the teeth. Dry granite was evidently one thing; wet granite was quite another. It might as well have been ice, to anyone in running shoes. We had to sit and slide or else walk in the stream the whole 2,000 feet—of altitude, not linear feet. It took us over three hours. We still couldn’t see more than three or four feet ahead of us—enough perhaps to keep us from stepping over a precipice, but not enough to give us any sense of direction. Then Hasting Street came to an end.

By far the most difficult part was getting from the end of Hasting Street to the place of the rock cairn. Coming up, it had been tough enough, the scrambling up and over and down—cliffs above us and precipices below us. But now we couldn’t see where the cliffs were, or how close the drops—it was nerve-racking.

We stopped for ten minutes’ rest. Doc broke off a chunk of cheese for each of us to keep us going. As we sat there, on boulders, young Peter picked up a stone and lobbed it into the fog. It disappeared . . . but didn’t land . . . Seconds later, we heard it land a long way below. Peter sat down suddenly and held on. We were not more than ten feet from the edge of that drop. Doc felt fairly sure that we had either missed the cairn, or were within a hundred feet of it. There had been only one sheer drop as deep as the sound of that stone between the cairn and Hasting Street. We tried it again with stones, and counted the seconds until they hit. It still didn’t tell us which side of the cairn we were on—but it did tell us that there was a four-hundred-foot drop.

We couldn’t leave each other to scout ahead, but we tried to estimate the number of feet we covered now. Also we put stones on top of the rocks so that we could find our way back to the cliff—if we decided that we had already passed the cairn where we should make a turn.

“There it is!” a woolly voice cried. It was six feet to the right. In shrinking away from the cliffs, we had almost over-shot our marker.

The fog thinned momentarily, as though we had done our bit so it would help a little. Doc plunged ahead, with the rest of us like a comet tail behind him, seizing the chance to locate the huckleberry patch. That would mark the chimney we had to climb down towards the trapline with the blazes. Finally there was a shout from Doc—there they were, and there was the chimney. The fog closed down again before we quite got to it. Again we held hands, and advanced cautiously towards where we had spotted it. One by one we took off into space, with the horrible thought that it could be the wrong chimney. We hung on tooth and nail, dislodging stones and earth in our urgency. Another shout from Doc—there was a tree . . . there was a blaze—we were safe.

We got out the primus, and while we were waiting for the water to boil we wrung out the sleeping bag and blankets again. We munched bully-beef and rye-tack, and finished up with peanut butter. Then we sank as deep as we could in our mugs of hot tea.

Two thousand perpendicular feet below we came out into bright sunshine. Two thousand feet more and we were back at the wharf. Nobody had been worrying about us at all. It was just another lovely day, down in the inlet. We made our squishing way to the dinghy and back to Trapper’s Rock. There we fell into the sea—clothes and all. How warm the water felt, how hot the last rays of the Louisa sun!

We cooked ourselves a great pan of bacon and eggs—a big pot of coffee, and great spoonfuls of honey on top of peanut butter and crackers. Enjoyment is always greatest when you have enough contrast to measure it by.