Knight Inlet

It was still blowing too hard for us to start on the long Knight Inlet trip, but it was time I got my crew back on camp fare. We had all just finished making up my mind that, unless the weather changed, we would go on up to Kingcome Inlet in the morning, when we sighted a ketch working in towards the Indian Anchorage. The old fisherman hurried up onto the bluff and waved them round towards his wharf. The ketch went about, hauled down her sails, then “putted” into the wharf and tied up beside our boat.

We knew the people, and they were going up Knight in the morning. Weather that was too windy for our boat was just perfect for the ketch. Before the evening was over, it was all settled that we should transfer our sleeping bags to the ketch and make the trip together. We could leave our boat tied up just where it was.

We were under way by eight o’clock—with engine. Out by Eliot Pass and Warr Bluff to take advantage of the tide, which would be quite a consideration for the first ten miles or so. The ketch was about thirty-seven feet. With the four youngsters they already had on board, and my three, we were full up but still comfortable.

We had hardly cleared Battle Point when the morning wind caught up with us, and with it some quite unexpected fog—soft and rolling. It would roll down the open channels in great round masses—hesitate for an island, and then roll over it and on. It would fill up all the bays—searching and exploring. It came on board and felt us all over with soft, damp fingers, and we hoisted our sails and fled before it. We escaped before we were very far past Protection Point, and left it rolling up Thompson Sound to see what it could find up there.

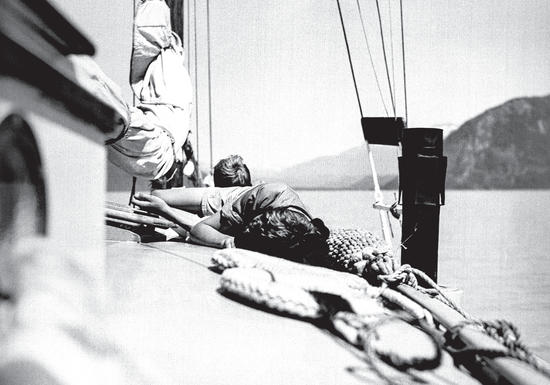

Then the sun came up over the mountains, and the wind increased until we were making six or seven knots running before it—quite fast enough if you want to enjoy the surroundings and not give all your attention to the sailing. Soon though, it was impossible to forget the sailing on Knight—which writhes along through the mountains like a prehistoric monster. With every next mountain or valley, the wind took a completely different direction. The big sail would jibe across with a “wha-a-am.” We would no sooner get it settled on that side when “wha-a-am” back it would go again.

A little farther on, the wind blew harder, but it was steadier. The mains’l, which had been hauled down, was hoisted again. The mountains grew higher and higher, and gossiped together across our heads. And somewhere down at their feet, on that narrow ribbon of water, our boat with the white sails flew swiftly along, completely dwarfed by its surroundings.

We slopped badly in a beam sea when we turned into Glendale Cove, and some of the crew felt a little squeamish. But we were soon out of it and tied up to a wharf inside a boom-log. We intended to spend the night there, for as far as we knew there would be no other anchorage until we were near the head. A little later, watching the big white combers rolling white and wild up the inlet, we decided that any sailing for pleasure up Knight had better be done in the morning.

There is a salmon cannery in Glendale. While we were there a packer came in with a load of fish. The manager invited us up to watch operations. Most of the operators were Indian women. We watched the fish leap from the packer onto the endless belt, onto the moving tables where the Indian women waited with sharp knives, and then into the tins, in an unbelievably short time. So fast that you still seemed to sense some life in the labelled tins . . . We rowed up to the little river at the end of the cove, and had some warm fresh-water swimming. There was supposed to be a lake, but we couldn’t find the trail.

We left Glendale at five-thirty next morning. As we had hoped, Knight still slept. Great clouds hung low and white, tucking him in like a great downy comforter—and we tiptoed past in the quiet, grey dawn.

Knight Inlet averages about one and a half miles in width. Jervis Inlet about a mile. The mountains are about the same height in each—but Knight gives you an entirely different impression. It is bolder, the reaches are shorter. You no sooner get well started on one reach than a stupendous mountain, sitting on a great cape, shoulders you aside without any apology. You stagger across to the other side, only to be just as rudely shoved back the other way. The mountains in Knight don’t just line your way—they block it. Perhaps it was because I was on someone else’s boat and not my own, but I have never felt so insignificant, anywhere on the coast, as I did in Knight Inlet.

Then gradually, one by one, the snowy peaks tossed the clouds aside and raised their shining heads to watch us pass, turning, as we did, to show new beauties of some different facet. Then a light breeze drifted up the inlet and made varied patterns on the quiet water. We set our sails, which gradually filled, and helped to carry us gently forward. Long shafts of sunlight crept through the valleys to strike the opposite snow-capped peaks. Down . . . down . . . the shafts slowly dropped and spread . . . then caught and held our white sails. We stretched cold, stiff limbs; the mist rose off our dripping decks and canvas; we shouted, and the sleepy crew streamed up on deck to greet the sun.

We had cups of hot tea to warm us up. Then sat there in the sun, watching reach after reach unfold to reveal something still more lovely. When it became apparent that it was going to be after lunch before we reached Cascade Point, where we were to look for twin waterfalls, we cooked our breakfast and ate it on deck.

The great blocky bulk of Tsukola and Cascade Point thrust themselves out . . . and out. We were too close to see the six-thousand-foot mountain that lay behind. Then just past Cascade Point the Twin Falls leapt into view, divided from each other by a sharp ridge of rock. There was no place there to anchor; but three or four miles farther on, in Glacier Bay, there was a small logging camp. We tied up behind their boom. The children spent the next couple of hours playing in a spur of snow that came right down to the water’s edge. Glacier Peaks lie behind the bay—two or three miles inland. I think the spur of snow must be where the old glacier has retreated. Early records mention it as down to the sea. We could have stayed where we were for the night, but when we asked the loggers about possible anchorages, they told us of a place just beyond Grave Point, on the opposite side of the inlet where a valley cuts the mountain. It is marked forty fathoms, no bottom, on the chart; but they told us that, in the left-hand corner, we would find a little beach and creek, with anchorage in ten fathoms.

We found everything just as they had said. That evening we built a great beach fire on the shore of Ahnuhati Valley, and watched the light die off the purple mountains with the white tops on the opposite shore.

We had decided on another early morning run, unwilling to miss the sight of Knight asleep, and Knight awakening . . . So we left the shores of Ahnuhati Valley and crept out past Transit Point, with Mount Lang and Mount Dunbar white and cold in the sky above us. Then, quite suddenly, we were in glacial water—and we slipped over a sea as dense as milk, which hid all beneath us. Captain Vancouver in his diary speaks again and again of the milky water they encountered at the ends of the inlets. They made many guesses, but never the right one. We slowed down a little . . . gave the capes a little more room. There was nothing else we could do.

Then, still surrounded by the early mists, for it was too soon for the sun to top those sleeping mountains, we slipped into Wahshihlas Bay for breakfast. Afterwards we landed on the wide sand flats to stretch our legs. A rather extraordinary place for sand flats to be. Great rocky Hatchet Point to the north, and Indian Corner to the south. Two miles inland, and centred in the middle of Wahshihlas Bay, Mount Everard rises up in a perfect cone to seven thousand feet—the upper three thousand covered with snow. Although you cannot see it, it is joined by a narrow hog’s-back to another peak directly behind it—the same shape and same height. The drainage from that double mountain must sweep the sand out through the bay, and then drop suddenly into those milky depths.

To reach the more solid sand we had to wade through one of those glacial streams—so cold that we were numb to the knees. We raced to get warm, our bare feet sinking into the soft damp sand. Suddenly, beside our footprints, we spied a great webbed footprint . . . Robinson Crusoe-like, we stared—then a great goose, with a loud “honk-honk,” flew out of the reeds and flopped down some yards away. We chased it with outstretched hands—again and again it flew and flopped—and again and again we chased it . . . All at once it dawned on us that we were doing exactly what she wanted us to do—and we ran back to find her brood.

“Honk-honk!” warned the mother goose, and not a gosling stirred.

There was no hurry—it was only ten or twelve miles up to Dutchman Head, which, as far as that deep-keeled boat was concerned, was the end of the inlet. We could either stay near Dutchman Head for the night or come back to Wahshihlas Bay to get a good start down the inlet in the morning. We would be bucking wind the whole way down.

When we got well out beyond Hatchet Point we could see the sun shining on the great glaciers that stretched towards the east. The still larger one to the west was obscured by high mountains. We could see nothing much below the surface of the water, and when the lookout in the bow called out “Deadhead!” we had to slow to a crawl. Deadheads are big logs, almost waterlogged, that float straight up and down. Many of them have a couple of feet showing above water, but just as many are floating a foot or so below the surface. They can rip a bottom out, or tear a propeller off. This last reach was full of them; and also with great stumps that floated with their roots all spread out like tentacles.

We “putted” along, barely moving, with four lookouts up in the bow, and gradually worked our way across to Dutchman Head. It was too deep to anchor, so we tied on to a deadhead that seemed fairly stationary. We were at once attacked by starving deerflies—something like horseflies, but bigger, and grey in colour with pointed wings. You could kill them on your legs at the rate of one a second. We had to eat our lunch below—on deck there was not a chance to get a bite in.

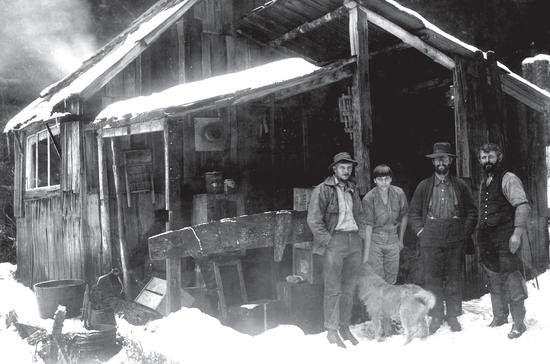

We had a parcel for the people who lived near Dutchman Head—the only white inhabitants of the region. They had lived there for years and the man was a well-known guide and trapper. So we landed all the youngsters on the flats of Ah-ash-na-ski Valley, then rowed over to the new log cabin. I could see the children racing around waving bunches of reeds—evidently the flies were bad in there too.

The cabin was delightfully dark and cool after the glare and heat outside, and it was well screened. They told us that the flies only lasted six weeks, and were over by the time the hunting season began. But up in the mountains there were no flies anyway, just down in the valley.

The talk turned to hunting, and then naturally to grizzlies, which abounded and promptly killed any other animals they tried to keep. The man offered to put us up a tree later, where we could safely watch them feeding below. No, he had never heard of grizzlies climbing trees, their claws were too long. Every afternoon about four o’clock half a dozen of them and some cubs came down to the flats to catch fish and feed.

“Funny thing,” he said, “they never seem to go for women or children—they don’t pay any attention to my wife, but as soon as they see me they come straight for me—they don’t like men.”

“What flats do they come to at four o’clock?” we asked.

He pointed. “Along there, at Ah-ash-na-ski Valley.”

We got hurriedly to our feet and looked at watches. It was now almost half-past three. The boys we had left on the flats ranged from fourteen down to five. Just when did a grizzly consider that a boy had reached man’s estate? Was four o’clock the same on a sunny day as it was on a dull day? Or did it just depend on when the bears felt four-o’clockish, and simply had to have their tea? Our reactions were simple and to the point . . . we rowed wildly to the rescue, our shouts drowned in the roar of the streams. Not a single child paid any attention to us. I transhipped the others to the ketch to start the engine and follow—the dinghy would not hold everybody.

It wasn’t until I ran right up to the children that they heard me; they were busy examining the huge spoor of those same chivalrous grizzlies that never touched women or children, but always made for the men. I explained in a hurry—and we reached the dinghy all at the same time. No one would go back for a line they had left under the tree, and nobody breathed quite properly until we were safely on board the ketch.

We made a hurried tea before we faced the deadheads and the flies. The tracks of the bears grew longer and longer as the children told the story and argued.

“Look! Look!” they shrieked, and we scrambled up on deck after them.

There under the tree on the flat were five big bears—twice the size of black bears—and three small cubs—all smelling the footprints the children had made under the trees . . . lifting and swinging their noses high in the air . . . trying to trace where the intruders had gone.

“Who’s been stepping on my sand?” growled John. And all the youngsters took up the cry, and the bears came closer and looked at us.

The trip down Knight was wearing but uneventful as far as Ahnuhati Valley, where we were thankful to creep into the little bay and get out of the wind. Once more our fire at night lighted up the surrounding cliffs and water with its flickering flames. And once more the sense of humility at the feet of the reaching mountains.

We left at six in the morning, hoping to get to Glendale before the worst of the wind got up. It always blows up Knight in the summer, gathered and funnelled in from the open Pacific. But the wind had similar ideas about an early start, and before long our small engine could only push the heavy boat at a poor three knots—pounding into the seas, the spray flying high. Finally we put up the jib and mizzen to steady us, losing time but gaining in comfort. Then the engine sputtered . . . and died. There was little or no room to tack, with every shore a lee-shore and no possible anchorage. One of us tried to keep the boat in mid-channel, while we drifted backwards or stood still under the two little fluttering sails. After a long, long time the trouble was diagnosed—and once more we fought our way along.

It was rolling high and white when we reached the more open stretch off Glendale. After struggling ahead for a while to get a better slant, we tacked into the bay under a reefed mainsail. It was three o’clock before a very wet and weary crew lowered the sail and moved in behind the boom.

Once more we left at six o’clock—the wind too. At eight, uncertain of our engine which was acting up, we took shelter behind a log boom which was also taking shelter behind an island. At five o’clock in the evening it began to rain and the wind dropped a little. We started off again hoping to get to Minstrel Island for the night. But at dusk, wet and cold, we thankfully crept into Tsakonu Cove, in behind Protection Point. We anchored and stumbled below to get dry and fed, only to hear a shout that the anchor was dragging.

There were no waves in there—but it was low land behind, leading through to a bay on another channel, and the wind blew through and we dragged right out of the bay. Twice we dragged—the bottom was evidently round stones from the creek at the head. Then we put down the big eighty-pound kedge and got some rest.

It was good to see our own little boat again and to find her safe, but rather smaller than I remembered—Knight would have been a little tough in her.