Speaking of Whales

Where do you come from? Where are you going? I would wave a vague hand behind me. “Oh, from the south,” I would say evasively, or, “Oh, just up north—nowhere in particular.”

What did it matter to anyone where we went? We ourselves usually had some idea where we intended to go. But we seldom stuck to our original intentions—we were always being lured off to other channels.

Sometimes that wasn’t our fault. One summer we seemed to be beset with whales. Northern waters were a little strange to us then; and so were the particular kind of whale they had up there. We were used to the killer whales, which we often saw in southern British Columbia—they were black with the white oval splash that looked like an eye, and they were white underneath. They also had high spar-fins, sometimes four feet in height. You seldom saw them alone—they went around in packs. They would go charging through the narrow pass at home—blowing and smacking their tails. “Killers in the pass, killers in the pass,” the children would shout, from here and there. And everyone would race down to Little Point to count them through.

The ones we saw up north were grey, or perhaps a dirty white—and very big, twice as long as our boat. They often lazed around on the surface, just awash, and blew huge spurts of air and water up into the air. You would see the spurt, and then have to wait until the noise reached you—something like a pile of bricks falling slowly over—and the sound would echo from cliff to cliff, until it whispered itself out.

They would patrol backwards and forwards . . . backwards and forwards . . . across some inlet we wanted to go up . . . and we would meekly turn back. They didn’t appear to be feeding—just pacing the water. Perhaps they were waiting for their babies to be born—which is rather a critical proceeding. For when the baby is born into the water, the mother whale has to put her flipper round it and rush it to the surface to take its first breath, or else it will drown. Then it has to be initiated into the business of nursing. The two nipples are up near the bow of the whale, just behind the head. The nursing is probably, in the beginning anyway, a near-the-surface operation. The baby whale does not exactly suckle. It takes the nipple in its mouth, and the mother ejects a huge supply of milk into the baby in one blow—and that is all for another half-hour, when the procedure is repeated.

That same summer, going back by Johnstone Strait on our way south, we were overtaken by a whole pack of killer whales. We didn’t hear them coming—they were just suddenly there, on all sides of us, big ones and little ones—all just playing. There must have been about twenty of them—chasing, diving, ducking and rolling with tremendous slaps of their tails. When you see the spar-fin of a big killer breaking water, it is like seeing the mast of a fishing boat appearing from behind a swell on the skyline.

The biggest of these were around thirty feet, with a fin four or five feet in height. When one of them breaks water the head comes up first; then it submerges and the spar-fin rolls up. Just as the fin disappears, a flange of the tail rolls into sight, looking like another fin, but smaller. Then with a tremendous smack of the tail, the whale submerges.

But this pack were not travelling, they were playing—putting in time. One of the big ones chased or pushed a smaller one straight up in the air, clear of the water; and its chaser followed, out to the shoulders. One of them surged straight for the shore when chased. He hit the shallow water with a force that stood him straight up on his head—a great bleeding gash showing on one side. He fell back and somehow managed to struggle back into deep water. Our fears increased after that. There was nothing to prevent them coming up underneath our boat—quite unintentionally.

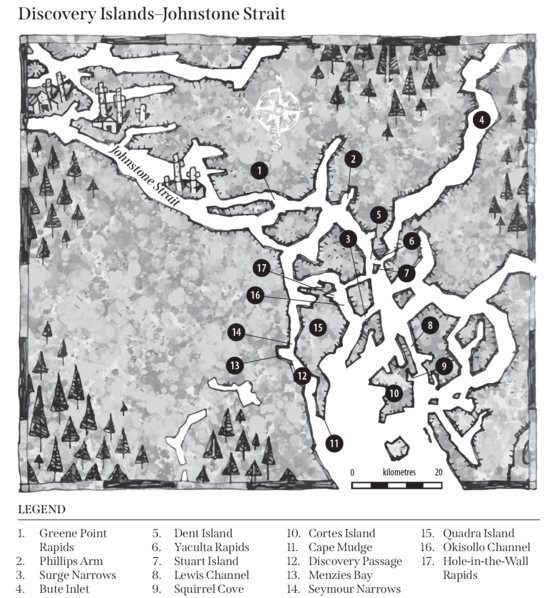

But we couldn’t escape from them—they were between us and the shore, and on all sides of us. We couldn’t hurry, we couldn’t lag behind—they either hurried too, or else waited for us. Mile after mile . . . at last, at some unknown signal, they all dived deep at the same moment—and the sea was quiet and empty, and our ears rang in the stillness. When next they surfaced they were heading full speed up a channel which, if they intended to continue south, would take them through the Greene Point Rapids.

“Do you suppose they wait for slack water?” said Jan.

“Perhaps that’s why they were just fooling around,” suggested Peter.

“I didn’t like that fooling!” said John.

I got out the tide book, and looked up the slack water tables. Slack water has not necessarily much to do with the height of the tide. Yes, it was just half an hour before slack water in the Greene Points. If they hurried, they could get through the Greene Points, the Dent Island, and the Yacultas, all in the same slack. That was evidently just what they intended to do.

I revved up the engine and we chased after them. We couldn’t hope to get the whole way through, for it was a big run-in. But we could get through the Greene Points, and then cut in behind the Dent Islands and tie up for the night. The fishermen there would tell us what the killers had done.

“Don’t go too fast,” said John, anxiously.

“Oh, I can’t catch up with them,” I reassured him. We certainly wouldn’t care to be escorted through the rapids by a school of whales.

The killers are savage things. They normally hunt in packs. But once we saw a savage fight between a lone killer and a small grey whale—very one-sided, since the grey whales have no teeth. The killer had chased it into shallow water. They went round and round—in and out among the reefs. The killer must have been taking bites out of the grey one whenever it got close enough—the water round them was foamy and a bright pink. Then the grey one made a break for more open water—the killer hot on its tail.

They turned up a blind channel—so the outcome was not in much doubt.

Another time, near home, I was awakened in the night by the loud tail-smacks and blowing of killers in the pass. I could tell by the direction of the sounds that they must have turned into the bay. The next morning the children came running into the house to report that there was a crowd in the cove on the other side of the bay, all gathered round something on the beach. I took the binoculars over to the point, but I couldn’t make out what the crowd were interested in. We piled into the canoe and paddled across.

Most of the crowd had gone by the time we got there. But a group of fishermen were still standing talking beside a small grey whale that lay on its side on the mud. It was still alive. Every now and then it would let out a great gusty sigh. There was a big gash in one side, but not enough to kill it. The fishermen said they had also heard the killers in the night; and later they had heard the commotion in the shallows.

“The whole pack of them went ploughing right past our boats,” they said. “Evidently, they had all ganged up on this little fellow, and chased him right in the bay, where he got stranded.”

The sun was quite hot, and there wouldn’t be enough tide to float the whale until the evening. The men were throwing the odd pail of water over it to keep it damp. But the poor whale sighed, as though it didn’t think it would help much. I think they are like porpoises and have no sweat glands—without the water to keep them cool, they over-heat. That night the fishermen put a rope round its tail and towed it a long way out. It was still alive, but they didn’t seem to think it would survive.

Our clock is not very reliable—the tide had not quite turned when we reached the Greene Points but it had no force left. We played the back currents, and got through quite easily. Another twenty minutes and we could feel the push of the current. Once we passed Phillip’s Arms, I struck across over to the north side—the current carrying us almost as fast to the east as we made north. One of my nightmares is having the engine stop just above the rapids. If I didn’t get in behind Dent Island we would be swept into the worst of the rapids. A huge whirlpool forms in the centre there, and everything is drawn into it from all sides.

I let out my breath as we edged our way into the bay at the back of Big Dent. We tied the boat up to a boom log and ran across to the other side of the island to watch the big run-in. A couple of fish-boats were lying inside a boom, and we went across to ask them about the whales.

“Did the killer whales go through?” I asked the men.

“Sure, about an hour ago—they always wait for slack water.”

But they weren’t sure whether they waited because they didn’t like the current, or because it was the best time to fish. What we really wanted to know was, how the whales knew when it would be slack water.

We sat on the cliff and watched the whirlpools forming and moving across; then the final hole in the middle, swallowing up the sticks and logs. If you meet a whirlpool, you are supposed to decide calmly which side to take it on—one side throws you out, the other draws you in. I always forget at the critical moment which is which. However, there are many local stories of boats that have been sucked down, or had narrow escapes. One story the people tell is of a small fish-boat whose engine had stopped, and which was going round and round in a whirlpool. An Indian, seeing it from the shore, paddled out in a small dugout and took the man off—just as the boat filled and sank.

In the Arran Rapids, which are on the other side of Stuart Island from the Yacultas, a Catholic priest was being paddled through them by four Indians in a dugout. The priest was terrified when he saw what they were proposing to take him through, and began to pray out loud.

“Don’t worry!” the Indians told him. “Our gods will look after us. They always make a straight way for us through the rapids.” The priest said later that, in the middle of all that awful turbulence, there was a straight shining path, leading them the whole way through. When they had safely landed him, he fell on his knees to give thanks to God, and explained to the Indians what he was doing.

“Uh!” said the Indians. “We give presents to our gods first.”