The Skull

It was John who found the skull, or rather the bone that led to the skull. He was playing on the beach over in the corner near the waterhole, underneath a great old fir tree that grows on the edge of the bank where the solid rock slopes down lower towards the beach. This old tree doesn’t grow tall and straight the way they do in the forest. It sends out huge low branches almost as big as the trunk—as though it were easier to feed its hard won nourishment to the parts not too far away from the source. The great roots that embrace the rocks like an octopus and anchor the old tree to the bank are now exposed on the edge of the beach. The waves of the big winter storms have washed away part of the black earth mixed with shell, leaving the bare roots burrowing down into the sand.

“Mummy!” John called, as I came down onto the beach from the high knoll on the other side of the cove.

“I found a bone.” He crawled out from under the roots that framed a little house for him, waving a long, white bone.

Deer leg, probably, I thought, as I walked across to look at it . . . but it was no deer bone.

“I think you have found part of an old Indian.”

John dropped it, and wiped his hands on his shorts.

“Where did you find it?”

“In under that big tree.”

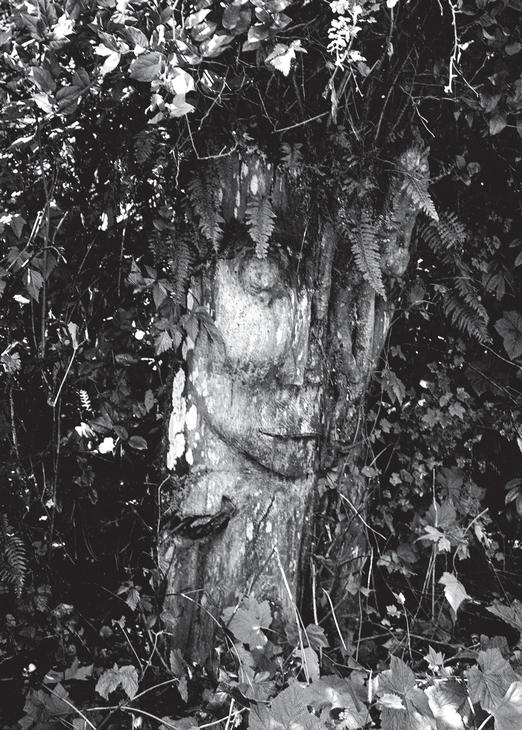

I took a piece of driftwood and poked about cautiously, close to where he indicated. Whoever it was had been buried before that tree existed. And the tree must be at least three hundred years old—the growth is slow on rock. Then, right up underneath the root crown I uncovered something broad and curved. I worked carefully with my hands, and finally lifted out a yellow skull, which looked at us wanly out of hollow sockets . . .

It was a flathead, the skull having been purposely deformed in infancy—usually with a board fastened so as to give continual pressure, or a cedar-bark pad while the bone is still soft. This one looked as though it had been bound with something as well, for it had a curious knob on the end. A flathead was a sign of nobility among some of the tribes on this coast, and only the upper class were allowed to deform their babies’ heads like that. I think this one had been a woman’s—it was too small and delicate for a man’s, but judging from the teeth, full grown. Who knows how old it was—the coast Indians didn’t usually bury their dead in the ground, but fastened them up in trees.

Just recently archaeologists digging in the big Fraser River midden have found proof (by carbon test, I presume) that Indians lived on this coast eight thousand years ago.

In the last twenty years, on southern Vancouver Island, every now and then someone finds a roughly carved stone head or figure. One, just a couple of years ago, was rescued from a man who was building it into a stone wall he was making. Another was turned up by a plough. I saw that one. It was carved out of coarse rough stone: elongated, pierced ear lobes, and rather Egyptian features. Both the stone and the carving called to mind some of the Toltec carvings in the museum down in Mexico. The present coast Indians don’t know anything about them, or who made them.

On examination, the land behind the little bay where we were anchored proved to be all midden—about ten or twelve feet deep. It lay exposed where a winter stream cut through. It was quite a small area, and probably just a summer camp. Across the main big bay, at what we call the Gap, are clam flats. The Indians most likely smoked and dried their clams for winter use, close to where they dug them. I don’t suppose they had any ceremonies in connection with the digging of clams—clams being immobile creatures, and not temperamental like the salmon. The salmon were treated with great respect. Once they started running—big schools on their way to the rivers to spawn—no venison must be eaten, lest the fish take offence and go off in another direction. After eating the salmon, the bones were carefully collected and thrown back in the sea—so that the souls of the salmon could return to their own country.

“We’re always getting mixed up with Indians and things, aren’t we?” said Peter, digging furiously.

“Specially me,” said John, holding tight on to his piece of old Indian.