Mamalilaculla

It was far too windy to venture up Knight Inlet that day. After studying the chart we decided to put in the time by wandering through the maze of islands over towards Village Island. There is an old Indian village there, Mamalilaculla, and we had never been in there before. The village was always, at least partly, occupied in summer time; for it had a Church of England mission and a small six-bed hospital for tubercular Indian girls.

The chart marked a cove on the southwest side of the island as Indian Anchorage. Anchorage is always difficult to find in the waters off Knight Inlet. A terrific sweep of wind blows through there from Queen Charlotte Sound, with all the force of the open Pacific behind it. Also, you have tides with a range up to twenty-three feet to contend with.

We found the Indian Anchorage without any trouble—out of sight of the village, and quite a long way from it. We anchored in about three and a half fathoms. The water was not very clear, but I rowed all around and could see no sign of any reefs, or any kelp to mark anything. And after all—it was marked as an anchorage. It was too late to explore further that night. Jan said she had seen the roof of a house or shed in the next bay to the south—but all that would have to wait until morning.

We woke to an embarrassing situation. We found ourselves trapped in a little pool—lucky not to be aground—and surrounded by reefs that we could hardly see over, unless you stood up on deck.

While we were eating our breakfast, feeling very foolish, an old Norwegian appeared on top of one of the reefs and, looking down on us, asked if we were all right. “You won’t get out of there for two or three hours,” he said. “You anchored too far in.”

We gave him a cup of coffee and he helped us free our dinghy, which was balancing on the barnacles. He was in a punt, and we followed him back to where, just round the point to the south, was another bay with his float connected with the shore, and his fish-boat tied up.

He took us up to meet his wife. On the way we passed a frame house—a regular cottage with windows, doors, a verandah and chimney. Just as someone else might have pointed out another house on their property and mentioned casually, “This is our guest house,” the old fisherman said, “this is our hen house.” It was full of hens—a hundred and fifty White Leghorns occupying a four-room cottage. They all crowded to the screened windows to watch us pass.

“Here comes the missus,” he said. I turned . . . down the hill came a stout, grey-haired, elderly woman with an ox-goad in her hand, followed by two oxen pulling a stoneboat with a water barrel on it. When she saw us, she turned and faced the oxen, said something to them and they stopped.

Only they weren’t oxen, they were cows. They were heavy, thick-set animals. They looked like small oxen and had rings in their noses. They gave milk, and cream and butter, and worked four hours a day when needed. They hauled the barrel to the well for water, carted all the wood for the winter from the forest, and ploughed and harrowed the garden. I had never seen cows working like this before, but the old man said it was quite usual on the small farms in Norway. They could be worked up to four hours a day without affecting the milk supply.

His wife was very Scottish and full of energy. They had a large garden with all kinds of vegetables and about half an acre of strawberries, protected from the birds with old fish-nets. The strawberries were just ripening, in the beginning of August, almost six weeks later than the south of the province. They had a good market for what they could produce in the summer, as well as eggs and milk all the year round. I wondered where on earth their customers lived in this land of apparently no habitation. There was the Mission, but the rest of the customers lived at distances from fifteen to twenty miles away—in logging camps, or the cannery half-way up Knight Inlet, and the store over in Blackfish Sound. If the customers couldn’t get to them, the old man in the fish-boat would deliver to them on his way to the fishing grounds. They always had orders ahead for strawberries.

We lay at their wharf for three days, waiting for the wind to drop. We bought milk and cream, vegetables and eggs; and helped them pick crates of strawberries in return for all we could eat ourselves. This was an unheard of luxury on board our boat. There were various places that we had got to know, over the summers, where we could get fresh vegetables—but strawberries and cream!

One afternoon, one of the missionary ladies walked over the trail from the Indian village and had tea with us. We all sat under the tree, up on the mound overlooking the wharf. She was a most interesting woman, and broadminded. She had been at the village for years, and was in charge of the little hospital. She and her companion were both English—I think the Mission itself was English.

She had many tales—there had been one old woman in the village who was slowly dying. She kept saying, “Me want Maley, me want Maley” over and over again. No one understood what or who it was she wanted. Even the other Indians didn’t seem to know. Suddenly this missionary had a brain-wave. She looked through all the old books and magazines she had—until she found a picture of the Virgin Mary. She pasted it on a piece of cardboard and took it over to the old Indian.

“You should have seen that old woman’s face, as she whispered ‘Hail Mary’,” said the Protestant missionary—adding, “I was glad to have made her happy.” As far as the Mission knew, there had been no Catholic priests in the district for over eighty years. These Kwakiutl Indians had resisted missionaries and civilization much longer than the other tribes on the coast. The old woman might have been captured from some other tribe.

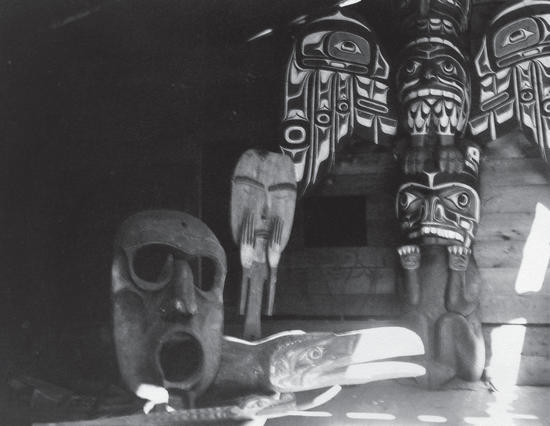

“But it’s discouraging at times,” said the missionary. For just when, with the help of the nursing and the religious teaching, they thought they had the feet of the village well on the road to civilization, they would come across something that made them realize that, below the surface, the Indian trails were still well trodden. One winter’s day they saw some strange Indians arrive in the village by dugout. Ceremonies were held that night in the big community house. The sounds of long speeches, singing and the rhythmic beating of drums came down the wind—all night. In the morning the strangers left.

Inquiring cautiously, she was told that it was the ceremony of “The paying-of-the-tribute-money.” The visitors came from a little village up on big Gilford Island. Once it had been a large village, with a powerful chief. But the Indians of Mamalilaculla, forty years before, had raided it and killed and burned and plundered. They had lost many of their own warriors in the raid, and for that, the little village, which had never recovered, still had to pay tribute or blood-money to their conquerors—the village of Mamalilaculla.

The missionaries had tried to tell the people in the village that it wasn’t Christian to keep on exacting tribute all these years. But they could do nothing—the strange Indians still appeared every winter. She didn’t know how much they had to pay, or what the tribute was. The old men of the tribe would not talk about it any more. It was a closed book, as far as she was concerned.

She asked us to walk back over the trail to see the village and the mission. It was a lovely walk through the tall hemlock. The path was wide and well trodden; for it led also to the Indian Anchorage, which the Indians used in winter for their fishing boats. All the Indians were away now, only the sick people and the old ones were left behind in the summer time. Captain Vancouver and his officers, in 1792, had never understood all the deserted villages. They thought the people must have been killed off by battle or plagues—whereas they were just following their usual custom of going off for the summer, as they still do. These old villages are their winter villages.

Miss B. said she had done her best to have the young Indian girls learn the ancient arts from the old women of the tribe, but none of them were interested. She took us over to a small house to look at some fabric that an old woman was making. She was the only one left in the tribe who knew how—and the art would die out with her. Miss B. did not know what it was called: she had never seen any like it before.

We didn’t see the old Indian working—she was sick that day—but we did see her work . . . In the Kwakiutl village of Mamalilaculla, on the west coast of British Columbia, this old, old woman of the tribe was making South Sea Island tapa cloth out of cedar roots. The cloth was spread across a heavy wooden table—a wooden mallet lying on top of it.

I am not quite sure how tapa cloth is made. But I believe they soak the roots in something to soften them—lay them in a rough pattern of dark and light roots, and then pound them with a wooden mallet into paper-thin, quite tough cloth.

The early explorers often used to winter in the South Seas, and at times had some of the islanders on board their boats on these coasts. There must be some kind of a connection somewhere. Even the liquid sound of the name of this village, Mamalilaculla, is more like the language of those far away islands than it is of most of the Kwakiutl dialects.