Karlukwees Village

It was dusk before we dropped anchor in Karlukwees Bay. It had been slow work feeling our way through the kelp-choked passages, and now it was too late to explore. Dimly above its shell beach the village curved in a half-moon on its high midden. A totem pole thrust itself up into the night. Great shadowy figures, cold and implacable, stared through the grey light at two small islands across the bay. Low white figures were keeping watch over there. One of them looked like a running animal of some kind—sinister, watchful. Burial islands, I guessed unhappily, as the night and the figures crowded close.

The whispering crew soon hushed to sleep. Somewhere behind a tall hill a late moon was hesitating to show itself. But in spite of my foolish tryst with her the night before, in Monday Harbour, I awaited her coming eagerly, for it was dark and lonely with the burial islands and all.

A swift tide thrummed its way through the massed kelp, and the eddies sucked and swirled over some hidden reef. If our boat sank in the night, it might be a couple of months before we were missed.

“That little white boat with the woman and children,” somebody would suddenly think. “I haven’t seen it around this fall.” But by this time the little crabs would be playing in and out our ribs; those horrible figures would still be staring over the water, and we wouldn’t be able to tell anybody that we were lying down there below.

We had just started our early breakfast next morning when a great northern raven discovered us and hurried down with welcoming shouts. He perched on a rocky point not far off and inquired about this, that, and the other thing. He chuckled over some of our up-coast news, and regretfully muttered “Tch—tch—tch!” over other bits. Then he proceeded to tell us all the winter gossip of the village as we ate our breakfast. They are the most extraordinary birds. They can ask a question, express sorrow or surprise, with all the intonations of the human voice. The old Indians credit them with unusual powers. A priest told the story of seeing an old Indian sitting smoking on the village beach. A raven alighted on the tree above the old man’s head and they carried on a conversation for some minutes—both apparently talking. When the raven flew away the priest went down to the beach and questioned the Indian . . . The old man was reluctant, but finally said, “Raven say, dead man come to village tonight.”

The priest rebuked him for such nonsense—the old Indian shrugged his shoulders and put his pipe back in his mouth. But that night a canoe brought a dead man back to the village.

Our raven was trying to tell us so much that we couldn’t understand. Finally, he flew away, “See you again,” he unmistakably croaked—and the place seemed empty with his going.

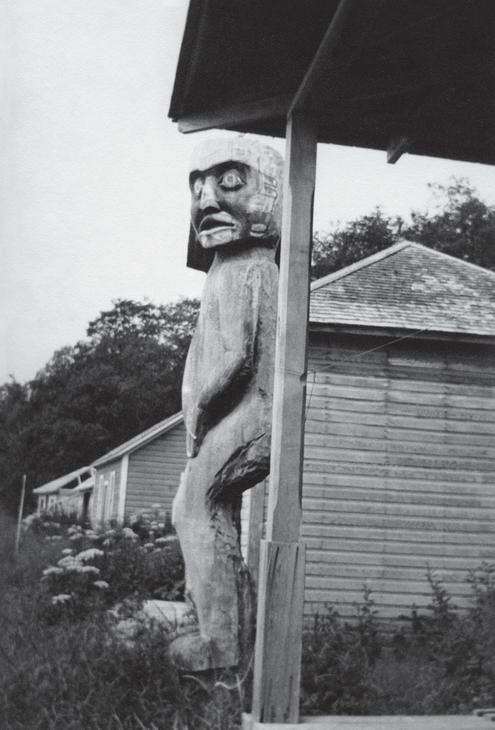

Once more we beat and laid the nettles low. Only one community house was intact in Karlukwees village, but there were remains of at least half a dozen more. Under the spell of the surroundings it was easy to see the old village as it must have been. The house posts in this one house were not carved, but were fluted like the big main beams. Out in front were two fine old carved ravens with outspread wings, standing on the heads of grizzly bears. A thunderbird sat on the edge of the midden and gazed across the bay.

I left Jan trying to sketch the thunderbird, and the other two picking up old blue trading beads; and worked my way through the nettles to a burial tree that I had spotted right back of the village. It was an immense fir, seven or eight hundred years old—so old that nothing could amaze it any more. Streamers of lichen dripped grey from bark and branches. Century after century it had stood there watching the fortunes of the little village at its feet. Had it rejoiced with them in the good times—times of plenty? Wept with them in the bad times—times of battle and famine? Or had it merely held their dead more lightly or more tightly, as required? There were nine or ten boxes still up there, clasped in its gnarled branches. Perhaps the old tree’s clutch was growing feeble, or perhaps it was too old to care—for when I stepped round its base to the other side, three blood-stained skulls lay there on the ground. I shrank back in horror . . . but making myself look again, saw that it was only dye off the burial blankets.

After lunch we rowed across to the burial islands. When tree burial was forbidden by the government the natives took to putting their dead on special burial islands, piling up the boxes in small log shelters through which the wind could blow. Each family or crest had its own island. The first one we landed on belonged to the wolf crest—a great running wolf thirty feet long, made of boards and painted white, with red and blue extra eyes and signs, stood guard over the dead of his family. On the other island, a killer whale proclaimed that the dead of his family lay there.

It was important in the Indian mind to be buried properly with carefully-observed rites. People who were drowned at sea could not go to the next world, but were doomed to haunt the beaches forever. Sometimes they were seen at night shivering and moaning, wandering along at tide level, seaweed in their straggling hair and phosphorus shimmering on their dripping bodies. Poor miserable drowned people . . .

I decided that I had to leave before nightfall. If anything happened to us in this Land-of-the-Past—and drowning was the most likely—would we have to wander the beaches forever—moaning and moaning? We were just visitors in this forgotten land—but how could we prove it, or who would believe us?

The sun was setting behind the hills when we left the old village—still so silent, still so indifferent whether we came or went. The thunderbird and the other carved figures still stared across to the islands-of-the-dead, where the last rays of the sun fell on wolf and killer whale. Silent, implacable, it was they who belonged here—we were only intruders; we would tiptoe away.

But as we rounded the last point, escaping, there was a hurried beat of wings, and our friend the northern raven flew croaking out of the dark woods and down to the edge of the cliff.

“What, going?” he chuckled . . . “Tch—tch—tch!”