Cougar

We never started off at the beginning of the summer expecting trouble or exciting things—at least, not after the first couple of years. Then, I think, we were looking for adventures. Later, when we found out what adventures were like, we tried to avoid them, but

they came anyway. So, after that, except for “exercising due care,” as the early explorers said, we neither anticipated them nor tried to avoid them. We just accepted them as a normal part of the increasing number of miles we logged every summer.

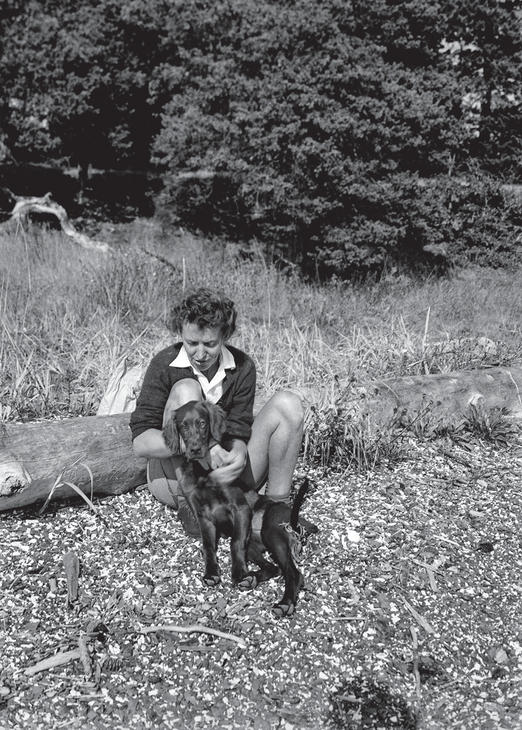

This summer we had exercised due care by leaving our Gordon setter at home. Other summers she had always come with us—enduring it rather than liking it, I think. She always had to tow behind in the dinghy, unless it was really rough. If we didn’t have the sense to know when that stage was reached—she always did. Instead of lying quietly asleep on her sack in the stern-sheets of the dinghy, she would suddenly sit straight up. Her nose would swing from side to side, trying to decide what was blowing up, what the barometer was doing. She would look at the waves on one side of her, then on the other—turning over in her mind how long she would wait before she made her demands.

When the first spray from a slightly bigger wave reached her, she would put on her long-suffering, determined look and move up into the bow of the dinghy. Then the dinghy would yaw—first to one side and then to the other—Pam ageing visibly with each swing. She was completely deaf to every command to go back to her proper seat.

“Mummy,” Peter would plead, “she’s terrified!” Wily old Pam—salt-water crocodile tears streaming down her face.

“All right . . .” I would say grudgingly—knowing exactly what would happen at the next stage, when the waves got a little bigger. “Pull her in.”

Everyone sprang to the rope, while I slowed the boat down. Before they could pull the dinghy to within four feet, Pam would gather her feet together and, with a magnificent leap, land lightly on the after-deck—smiling broadly. Everybody patted her, everybody loved her. She curled up happily on the coil of rope and went to sleep.

Another half-hour and she sat up again—bolt upright. No need for her to look at the barometer—she knew. “When are we going to get out of this?” her eyes and set of her mouth demanded. I was standing up to steer now, and the youngsters were playing cards on the little table that was wedged in between the two bunks. There was a shriek of “Pam!” One leap had landed her in the middle of the cards. The next up against the back of my legs in the only few square inches left on the deck of the cockpit. She didn’t dare smile this time. Nor did anyone dare pat her.

John climbed up onto the steering seat beside me. “She’s very bad, isn’t she?” he said. “Is it very rough?”

“Oh, no,” I said. “Pam is just being silly. See that point over there—we go in behind that.”

“Where?” asked Jan, moving up beside me.

“My, it’s rough!” said Peter, pushing in too. “Pam always knows, doesn’t she?”

“How am I supposed to steer, with a dog lying on my feet, and my silly crew jamming both my arms?” I demanded.

But all that was not why I decided to leave her at home this time. It was what happened last summer on our way north. We had anchored in Melanie Cove off Desolation Sound for a few days to enjoy the warm swimming. Then it clouded up and started to rain. The mountains back of Desolation Sound seem at times to be a favourite rendezvous for clouds that are undecided where to go. They drape themselves forlornly on all the high peaks, trail themselves down the gorges, and then unload themselves as rain on the sea at the mountains’ feet.

Pam had either to sleep on shore at night or else in the dinghy, which she prefers. That night it was so wet that I moved the boat over against the shore, on the opposite side from the copper stain on the cliff. There is an old shed there raised on short posts that is nice and dry underneath. Pam had spent wet nights there before, so she knew the place and raised no objections. The children rowed her ashore, fixed up a bed of bracken for her, and left her with a dish of food.

Then we got the Coleman stove going and supper on, and were soon dry and comfortable. It was surprising how comfortable we could be on a rainy day in that little boat. With the heavy canvas side-curtains buttoned securely down, the back curtain stretched open at an angle for fresh air—the two-burner stove on top of the steering seat would soon dry all the inside of the boat and us. We got the sleeping bags out early, and everything straightened. Unless we were sitting round a fire on the beach or rocks we always turned in before it was quite dark. It was a dead calm night, with not a sound except the hiss of the falling rain and the plop of the raindrops as they hit the sea and made little spurting craters.

I don’t know how late it was when something wakened me. I listened . . . trying to orientate myself . . . trying to remember just where we were anchored. Then Pam whined—and there was something desperate in the tone. I groped for the flashlight and unfastened the curtain beside me. It was still pouring. I shone the light towards the shed—but there was no sign of Pam where they had made her bed. Another whine from somewhere nearer us than the shed. I swung the beam down the shore to the edge of the water. Another whine, and I had to lower it still farther . . . There, up to her neck in the sea, was Pam.

“Pam!” I said. “What is the matter?”

She glanced nervously towards the shore; then turned back and whined. Obviously she wanted to come on board; and obviously there wasn’t an inch of room. The dinghy, where she often slept in fine weather, was half-full of water—and the sky was giving us all it had. Pam didn’t like bears—but a black bear wouldn’t bother her, tucked under a shed like that. I coaxed and pleaded, and finally ordered her back to bed. Slowly . . . so slowly . . . she splashed back and got under the shed. There she sat—glancing first over one shoulder, then the other. I flashed the light all over the woods. I called. I talked loudly to scare away any bear that might be around. Finally, Pam went farther under the shed and curled up on her bracken bed. I hushed the questioning crew back to sleep, and went to sleep myself.

It was about six o’ clock when I awoke again. The clouds had broken up and a shafted sun was trying to disperse the mist. I unfastened the curtain and looked towards the shed. I needn’t have looked so far. There in the water, up to her neck, was Pam—looking like a sad seal that had just surfaced. How long she had been there, we didn’t know. We bailed out the dinghy, and two of the youngsters rowed ashore and took Pam off. I made them take her across to an island on the other side and race her up and down to get her warm, while I cooked a big pot of rolled oats for her. With heaps of sugar and evaporated milk, that must have been the morning of a dog’s heaven. Then we put her on deck in the sun. She was warm and dry and happy. But in spite of all the questioning, she wouldn’t tell anyone why she had done such a foolish thing.

After breakfast we pulled up the anchor and went round to Laura Cove to get some eggs from Phil, the old Frenchman who lived there. I told him what had happened in the night, and said I supposed it must have been a bear.

“Dat weren’t no bear,” said Phil, emphatically. “A dog don’t act that way about a bear. Dat were a cougar, an’ I suppose it will be atter my goats next.”

Pam got badly spoiled after that. She was a heroine—she had outwitted a cougar.

On our way south again, six weeks later, we called in at Phil Lavine’s again. As soon as he saw our boat, he hurried down to the float. Hardly waiting to say, “Hello,” he started off excitedly:

“Say, you remember dat night your dog stayed in de water all night? Well, de next night dat cougar got my old billy-goat on dat little island where I keep ’im.” He pointed to a small island not very far from where we stood. He had heard the old goat bleating or screaming at about four in the morning, and knew that something was wrong. He grabbed his gun; ran down to the float and rowed across. There was a great round boulder on the beach, and he could see the head and shoulders of the goat sticking out on one side. The goat was lying on the ground and he thought it might have broken its leg, for it kept making this awful noise. He stepped out of the boat and started towards it—then turned back and picked up his gun.

“Atter dat dog of yours I weren’t taking no chances,” he said. He skirted out and around the boulder . . . There, hanging on to the hind-end of the goat, was a full-sized cougar.

“I got ’im first shot—between de eyes . . . den I ’ad to shoot de goat.”

We followed him up to the woodshed, where he had the skin pegged out on the wall. It was a big one, eight or nine feet long. Pam gave one sniff at it and slunk back to the boat.

“See!” said Phil, “dat ain’t no bear-acting!”

I realized it wasn’t—Pam barks hysterically when she runs from a bear.

“Don’t you let dos kids of your sleep on shore wid de dog at night—ever. De cougar would be atter de dog, but de kids might get hurt too.”

Nothing would have induced any of them to sleep on shore again, with or without the dog—after seeing that skin.