Of Things Unproved

We scoured the shallows for a month that summer trying to find a seahorse. It seems a most unlikely thing to find in this latitude; but I read somewhere that one species had been found as far north as the English Channel. If in the English Channel, why not here?

Last year, after we got home, when we were looking up something else in the “Encyclopædia Britannica,” Peter pounced on the picture of a seahorse and announced, “I saw one of those last year!”

I looked incredulous . . . “I did, really, Jan saw it too.” I turned my gaze on Jan . . . Yes, Jan had seen it—but no one could remember where, beyond that it had been in a reedy, sandy place in shallow water. When I asked why on earth they hadn’t called me to look at it, Peter furnished the last proof.

“Oh, it was just swinging there on a weed, holding on with its tail, and we were collecting sand dollars.”

Jan said, “We did look for it again, but we couldn’t find it. Peter said it was a greeny-brown just like the weeds.”

When I asked if the head really looked like a horse, Jan said, “Well, it made you think of a horse.” And Peter said, “Oh, it did too, Jan, it looked just like the one in the chess set.” So the evidence was all there—everything but the place.

I set them to work trying to think. The sand dollars were the best clue, for we didn’t often see any. The north end of Denman Island was the only place they could think of where they had definitely found sand dollars—and also, we had been there that summer.

To go back through one whole summer, to the beginning of the summer before that, in a child’s life, is just about a hopeless task. Sometimes I have chased down the years on a sure clue, looking for a source—only to find that it was something I had read to them; they had played around with it in their minds, thoroughly mixed it up with fantasy, and a couple of years later presented it to me as an actual fact. Which, I suddenly realize, is a fairly good description of a seahorse.

Another fantastic thing about seahorses is the way they have solved the problem of excess population in the seahorse world. Mother produces the eggs, but deposits them in a pouch on father’s abdomen. It is father who goes around looking incredibly pregnant, for whatever length of time a seahorse’s pregnancy lasts. They both look carefully after their young—most unfish-like.

So it ended in our spending a month in the following summer back-tracking up the Vancouver Island side of the Gulf, scouring the sandy bottoms and reedy bays—looking for seahorses swinging on green weeds.

Whenever I can, I do two things with one effort. If I have to move rocks or earth when building something, or gardening, or some like project—it makes me very unhappy just to cart them off anywhere to get rid of them. If I can take the rocks out from where they are not wanted and, with practically the same amount of energy that it takes to throw them away, build them into a rock wall or incorporate them in cement work—I am supremely happy.

So, in the month we spent looking for seahorses, I carried on a second project at the same time. While the children paddled for hours in the shallows among the weeds, very concerned with an unlikely fish for which I had offered a good reward, I concerned myself largely with—where had Juan de Fuca actually gone when he was on this coast in the 1590’s?

Juan de Fuca’s story of his trip has reached us in a very roundabout way. It comes to us first via a seafaring man named Michael Lok, who wrote of it or told it to Richard Hakluyt. Richard Hakluyt, “by reason of his great knowledge of geographic matters,” and his acquaintance with “the chieftest captains at sea, the greatest merchants, and the best mariners of our [English] nation,” was selected to go to Paris in 1583 with the English Ambassador, as Chaplain. It was there, on instructions, that he occupied himself chiefly in collecting information of the Spanish and French movements, and “making diligent inquiries of such things as might yield light unto our western discovery of America.”

Hakluyt, who was at Christ Church, Oxford, lectured in that university on geography and “shewed the old imperfectly composed, and the new lately reformed mappes, globes, spheres, and other instruments of this art.” He wrote two or three books, as well as making translations from the Portuguese.

When he died, in 1616, a number of Hakluyt’s manuscripts, enough to form a fourth volume, fell into the hands of the Rev. Samuel Purchas—another divine interested in geography and discoveries. These manuscripts he published, in abridged form, in 1622 under the title Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes.

Until his death Hakluyt was incessantly employed in the collection, examination and translation of accounts of voyages and travels, and in correspondence with men anxious to receive and impart information—among them Sir Philip Sidney, Sir Francis Walsingham and Sir Francis Drake; also the cartographers Ortelius and Mercator.

So Juan de Fuca’s account of his voyage up the coast of British Columbia came down to us through someone who was used to examining and weighing reports that were either told to or sent to him.

In 1592, Michael Lok met Juan de Fuca in the Mediterranean. Juan de Fuca was a Greek by birth, but he told Lok that he had acted as pilot for the Spaniards in the Caribbean for forty years—so we can assume that Spanish was his language. He told Lok that he had been “sent out in 1592, by the Viceroy of Mexico, with a small caravel and Pinace, armed with mariners only, to find the supposed Straits of Anian, and the passage thereof into the Sea they call the North Sea—which is our North West Sea.”

He showed Lok the course he took—along the coast of New Spain (Mexico) and California, and the Indies now called North America. Lok says, “All of which voyage he signified to me in a great map or sea-card of mine own, which I had laid before him.”

Juan de Fuca continued up the coast until, Lok reports, “He came to a broad Inlet of the sea between 47 and 48 Lat. He entered there into, sayling therein for more than twenty days and found that land trending still sometimes N.W. and N.E. and N. and also E. and S.E. and a very much broader Sea than at the said entrance—and that he went by divers islands in that sayling.”

If they had rowed and sailed along the north shore of that broad inlet and by divers islands for twenty days—where would they likely have got to? Vancouver with the Discovery and the Chatham, big ships compared to the caravel, had followed the south shore right into Puget Sound, landlocked by all the Puget Sound islands; and had continued north on the mainland side frantically trying to find a passage through the mountains.

Juan de Fuca in his smaller ships would likely have followed the tides on the north shore and turned N.W. up by San Juan, “and other divers islands.” Somewhere close to Nanaimo, he would have emerged “into a much broader sea than at the said entrance [Flattery]” and all the Gulf of Georgia would suddenly have lain before him.

If he had sailed north, and northwest up the Vancouver Island side of the Gulf, in twenty days of rowing and sailing, from where he entered the broad inlet of the sea, he would have been about at Texada Island. Texada Island, at the south end, is where the Gulf of Georgia ends and narrows down into Stevens Pass, or a still narrower pass inside Denman Island.

Now, Juan de Fuca says, “At the entrance to said Strait, there is on the northwest coast thereof, a great headland or island, with an exceeding high pinnacle or spired rock thereon.”

There are really two islands there, although from the shore of Vancouver Island they appear as one. Lasqueti Island, about nine miles long and two wide, is close to the southern end of Texada Island, which is twenty-seven miles long and four wide.

The Coast Pilot, speaking of Texada, says, “The southeast extremity of Texada is rugged and precipitous . . . almost immediately over it rises Mount Dick, a very remarkable hump-shaped hill 1,130 feet high.” About Lasqueti, it says, “Mount Trematon, a singular turret-shaped summit, 1,050 feet high rises nearly at its centre.”

That is what we were looking at as we approached, and it is what Juan de Fuca and his men would have seen on the northwest side of the gulf at the entrance to the straits.

Twenty miles from the north end of Texada he would have entered the south end of Johnstone Strait. Averaging one to one and a half miles in width, they ran for one hundred miles. Beyond mentioning that they had landed on the shore and found “Natives clad in skins of beasts,” Juan next says, “that being entered thus far into the said Straits and being come to the North Sea already, and finding the sea wide enough everywhere, and to be thirty or forty leagues wide—he thought he had well discharged his office and done the thing he had been sent to do.” In other words he thought he had found the supposed Straits of Anian, and the passage thereof into the North Sea.

Out at Cape Flattery, the entrance to what Captain Vancouver called the Strait of Juan de Fuca, there is no such island or headland, nor turret-shaped rock. And Juan de Puca referred to it as a broad inlet of the sea—not a strait.

Vancouver says: “The entrance which I have called the supposed Straits of Juan de Fuca, instead of being between 47 and 48, is between 48 and 49, and leads not into a far broader sea or Mediterranean Ocean.” Later, since he couldn’t find the turret or pinnacle, he came to the conclusion that Juan had never been there at all.

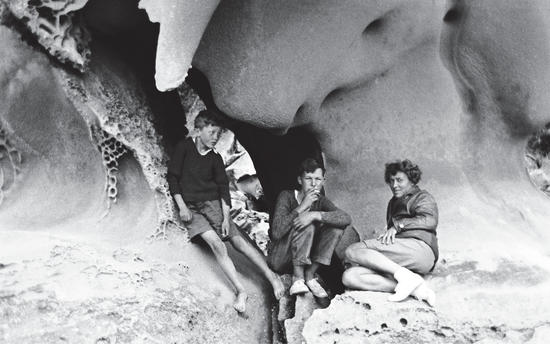

Still no seahorses, and the youngsters’ legs were getting a waterlogged look from so much wading. But it was not lost time, for they found and learned about many other things.

John came along the beach to me, grumbling, “Everything I find, they say it isn’t—and I think it is.”

“Well, never mind,” I consoled. “I don’t suppose anyone will believe that what I have found—is what I think it is.”

“Well, then,” said John happily, “I can say that I found a seahorse—and you can say that you found . . . what were you looking for anyway, Mummy?”

“I don’t really know.”