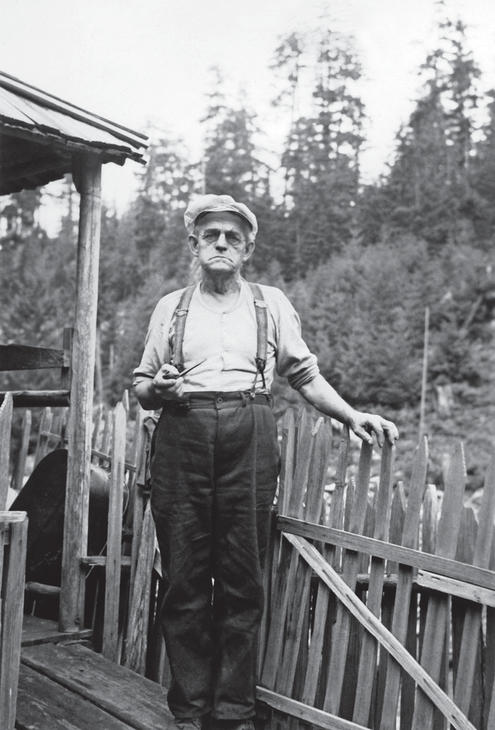

Old Phil

Phil Lavine, the old French man in Laura Cove, was full of calamities when we ran in to see him in July. He had had a bad winter. In the late fall he had something wrong with him, and had to go into the hospital at Powell River for a while. Then he had to come home sooner than he should have because the fisherman who was looking after his place for him wouldn’t stay any longer on account of the cougars.

Then Mike’s old place in Melanie Cove had been taken over by some fellow from Vancouver.

“A city man,” said Phil scornfully, “’e didn’ know ’ow to live in country like dis—’e was scared to deat’ all de time.”

In April, fish-boats that tried to anchor close in in Melanie Cove—the way they did in old Mike’s time—complained that someone was taking potshots at them. No one was hurt, and the police were a little skeptical.

“I knowed it was de trut’,” Phil said. “Dat fellow was gettin’ more crazy every day.”

The climax came one day when the fellow suddenly appeared and pushed his way into Phil’s cabin, with his rifle in his arms. Old Phil was sitting in front of the stove, smoking. The man didn’t say anything, but sat down in a chair opposite Phil with his gun across his knees, his finger on the trigger.

“’is eyes were crazy,” said Phil. “I t’ought it was de end of me.” Every time he tried to talk to the man, he pointed the gun at him. They sat there all afternoon—Phil smoking, but otherwise afraid to move.

Finally, the man, who had been getting more and more agitated, said, “Phil, you won’t laugh at me, will you?”

“My God!” Phil stuttered, “I ain’t got nuttin’ to laugh about!” and then added quietly, “I’ll make up de fire, an’ you stay an’ ’ave supper wid me.”

The man let him get up, and he made up the fire and put the kettle on. He continued talking quietly to him, and the man gradually relaxed.

Phil finally decided to risk it . . . he put the pot of stew on the stove, brought an armful of wood in from outside the door; he filled a tin with grain from a sack under the table, said he had to feed the hens before it got dark, and asked the man to watch the fire and stir the stew.

Then, still talking, he opened the door and went out and over to the hen house. He didn’t dare look back to see if he were being watched, but once round the end of the hen house where he couldn’t be seen from the house, he put the tin down and took the trail to the woods at a run. “I knowed I ’ad to get out of gun range before ’e discovered I weren’t comin’ back.”

He had a small mountain to climb before he could get help from anyone. It was only a rambling goat-trail, and it was dark when he finally stumbled into the Salter place. The two old brothers finally interpreted Phil’s French, gasps and signs—he had no English left. The three of them fell into the old fish-boat and didn’t stop until they reached Bliss Landing four hours later, and got in touch with the police boat.

“An’ we stayed right der until de police take ’im away. ’e was quite crazy, and now ’e’s locked up for good,” said Phil, rubbing his hands.

Phil was out of tobacco, and he was drying some green tobacco leaves over the stove—trying to hurry them up. Long before tobacco was produced commercially in Canada, the French habitants or farmers in the country districts of Quebec all had their own little tobacco patch, and grew and cured their tobacco for the winter. Phil had brought this frugal habit with him from Quebec. He showed us the little drying shed he had outside, where bunches of tobacco leaves hung from poles, drying slowly.

A baby goat bunted me suddenly and expertly, and the children laughed. I bunted him back with my fists and he jumped straight up in the air and landed with his four little black hooves bunched together.

“No more cougars, Phil?” I asked.

He pointed to two skins to the end of the woodshed, and shrugged: “Always de cougar, but wort’ forty-dollar bounty.”