Indian Villages

I throttled down the engine, lifted John up on the steering seat, and left the boat to drift idly under his care, while the rest of us unrolled the chart and tried to discover just where we were.

As far as the eye could see, islands, big and little, crowded all round us—each with its wooded slopes rising to a peak covered with wind blown firs; each edged with twisted junipers, scrub-oak and mosses, and each ready to answer immediately to any name we thought the chart might like it to have. To the northeast, the snow-capped mountains of the coast range reached with their jagged peaks for the summer sky. And north, south, east and west, among the maze of islands, winding channels lured and beckoned. That was what we had been doing all day—just letting our little boat carry us where she pleased.

But we were looking for old Indian villages, and we had to find out where we were. So we turned the chart this way and that way, trying to make it fit what lay before our eyes.

“We came through there, and along there, and up there,” pointed Peter, whose sense of direction is fairly good.

So we swung a mountain a few degrees to the west.

But Jan, who is three years older, snorted, took her pencil and showed us—“This is where we saw the Indian spearing fish, and that is where we saw the Indian painting on the cliff.”

So we meekly swung the mountain back again, and over to the east.

Then the channels began to have some definite direction, and the islands sorted themselves out—the right ones standing forward bold and green; the others retiring, dim and unwanted. We relieved John at the wheel; the other two climbed up into the bow to watch for reefs; and we began to make our way cautiously through the shallow, unknown waters that would eventually bring us to one of the Indian villages.

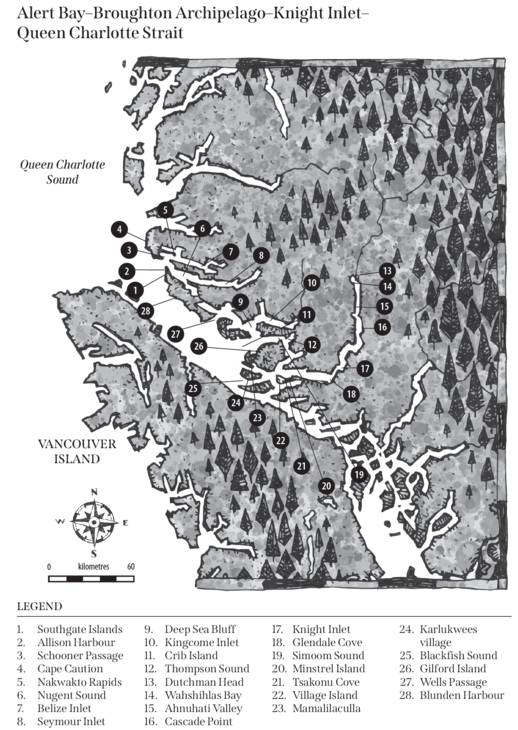

We were far north of our usual cruising ground this summer: in the waters of the Kwakiutl Indians, one of the West Coast tribes of Canada. Their islands lie among hundreds of other islands on the edge of Queen Charlotte Sound, well off the usual ship courses, and many of them accessible only through narrow confusing passages. In summer it is fairly quiet and sheltered; but in the spring and fall the big winds from the open Pacific sweep up the sound and through the islands, stunting and twisting the trees. And in winter cold winds blow down the great fiord that cuts eighty miles through the islands and mountains to the northeast. And at all times of the year, without any warning, comes the fog—soft, quiet, obliterating.

We had found an old stone hammer on our own land the winter before. It was shaped more like a pestle, which we thought it was. But trips to the museum, and books from the library, and a whole winter’s reading, had made us familiar with the history and habits of these Indians. So we had made up our minds to spend part of the summer among the old villages with the big community houses, and try to recapture something of a Past that will soon be gone forever.

There is little habitation in those waters, beyond the occasional logging camp or trading centre hidden in some sheltered bay. The Indians living among these islands have the same setting that they have had for hundreds of years, and cling to many of their old customs. It seems to give the region a peculiar atmosphere belonging to the Past. Already we could feel it crowding closer. And the farther we penetrated into these waters the more we felt that we were living in a different age—had perhaps lived there before . . . perhaps dimly remembered it all.

Yesterday, we had passed a slender Indian dugout. An Indian was standing up in the bow, holding aloft a long fish-spear poised, ready to strike. His woman was crouched in the stem, balancing the canoe with her paddle—a high, sheer cliff behind them. Cliff, dugout, primitive man; all were mirrored in the still water beneath them. He struck—tossed the wriggling fish into the dugout, and resumed his pose. When was it that we had watched them? Yesterday? a hundred years ago? or just somewhere on that curve of Time?

Farther and farther into that Past we slipped. Down winding tortuous byways—strewn with reefs, fringed with kelp. Now and then, out of pity for our propeller, we poled our way through the cool, green shallows—slipping over the pointed groups of great starfish, all purple and red and blue; turning aside the rock cod swimming with their lazy tails; making the minnows wheel and dart in among the sea grapes. In other stretches herons disputed our right-of-way with raucous cries, and bald-headed eagles stared silently from their dead tree perches. Once a mink shrieked and dropped his fish to flee, but turned to scream and defy us. Perhaps, as Peter suggested, he was a mother one.

We turned into more open water, flanked with bigger islands, higher hills.

“Mummy! Mummy! A whale!” shouted Jan, and almost directly ahead of us a grey whale blew and dived.

“Two whales! Two whales!” shrieked the whole crew, as a great black killer whale rose in hot pursuit, his spar fin shining in the sun. He smacked the water with his great flanged tail and dived after his prey—both heading directly our way.

We were safe behind a reef before they rose again. The grey whale hardly broke water; but we could see the killer’s make-believe eye glare, and his real, small black eye gleam. Then his four-foot spar fin rose and sank, the great fluked tail followed . . . and they were gone, leaving the cliffs echoing with the commotion. The Indians believed that if you saw a killer’s real eye, you died. It seems quite probable.

John recovered first. “I could easily have shot them, if I’d been closer,” he cried, grabbing his bow and arrow.

Nobody else would have wanted to be any closer. Some tribes believe that if you shoot at a killer, sooner or later the killer will get you—inland, or wherever you flee. Other tribes hail him as their animal ancestor and friend, and use him as their crest. But we were not quite sure of ourselves yet—we were just feeling our way along. Perhaps in some former life we had belonged to one of these tribes. But to which one? We had forgotten, but perhaps the killer hadn’t. We would take no chances in this forgotten land.

Once more we went our peaceful way, our lines over in hopes of a fish for supper. The engine was barely running—our wake was as gentle as a canoe’s. We rounded a bluff and there, on a rocky point, a shaggy grey wolf lay watching her cubs tumbling on the grass. She rose to her feet, eyed us for a second, nosed the cubs—and they were gone.

The distant hills turned violet, then purple. We anchored in a small sheltered cove, made our fire on the shingle beach and ate our supper. Then, all too soon, the night closed in.

About ten the next morning, away off in the distance, we sighted the white-shell beach. A white-shell beach is a distinguished feature of the old Indian villages, and every old village has one. Its whiteness is not a sign of good housekeeping but rather the reverse. These Indians in the old days lived chiefly on seafoods—among them, clams. For hundreds of years they have eaten the clams and tossed the shells over their shoulders. The result is that the old villages, which are believed to be the third successive ones to be built on the same sites, are all perched high up on ancient middens. Earth, grass, fern and stinging-nettle have covered them and made them green, but down by the sea the sun and waves bleach and scour the shell to a dazzling white. The beach is the threshold of an Indian village—the place of greeting and parting.

We dropped anchor between a small island and a great rugged cliff topped with moss-laden firs that bounded one end of the beach. Then we piled into the dinghy and rowed ashore. The place was deserted—for it is a winter village, and every summer the tribe goes off for the fishing. So, when we landed, no chief came down with greetings, no one sang the song of welcome, only a great black wooden figure, standing waist high in the nettles up on the bank, welcomed us with outstretched arms.

“Is she calling us?” asked John, anxiously, shrinking closer to me.

I looked at the huge figure with the fallen breasts, the pursedout lips, the greedy arms. It was Dsonoqua, of Indian folklore, who runs whistling through the woods, calling to the little Indian children so that she can catch them and carry them off in her basket to devour them.

“No, no! Not us,” I assured him. But he kept a watchful eye on her until he was well out of grabbing distance.

Behind the black woman, high up on the midden, sprawled thirteen or fourteen of the old community houses. The same houses stood there when Cook and Vancouver visited the coast. When Columbus discovered America, another group of buildings stood on the same site—only the midden was lower. Now there are shacks huddled in the foreground—the remaining members of the tribe live in them, white men’s way. But they didn’t seem to matter. One was hardly conscious of them—it was the old community houses that dominated the scene.

Timidly, we mounted the high wooden steps that led from the beach up towards the village platform. It was impossible to move anywhere without first beating down with sticks the stingingnettle that grew waist high throughout the whole village. In the old days the tribe would harvest it in the fall for its long fibres, from which they made nets for fishing. We beat . . . beat . . . beat . . . and rubbed our bare legs.

The village platform made better walking—a great broad stretch of hand-hewn planks that ran the full length of the village in front of the old houses. We tiptoed, as intruders should. A hot sun blazed overhead. The whole village shimmered. Two serpents, carved ends of beams, thrust their heads out beneath a roof above our heads and waited silently. Waited for what? We didn’t know, but they were waiting. I glanced over my left shoulder and caught the cold eye of a great wooden raven. But perhaps I was mistaken; for as long as I watched him he stared straight ahead, seemingly indifferent.

No one knows definitely where these coast Indians came from.

In appearance, language and customs they are quite different from the Indians of eastern Canada. They have broad, flat faces and wide heads. There is evidence that in earlier times there was another type with narrow heads and faces—but they have disappeared or merged with the others. There are as many different languages on the coast as there are tribes—each of them distinct and different from any of the others, and with no common roots; and all of them different from any other known language.

Unlike the eastern Indians who elected their chiefs for bravery, the coast Indians had a rigid class system. First the nobility, the smallest class and strictly hereditary; then a large middle class; and then the slaves, who were usually captives from other tribes, and their descendants.

Some ethnologists think that these Indians came across from Asia by the Bering Sea, and worked their way southwards. The Chukchi, who were the aborigines of Kamchatka, used to tell their Russian masters that the people across the straits were people like themselves. Other ethnologists think that they have drifted north from some tropical island of the Pacific. Many of their customs and superstitions are the same. Some customs, whose origin they have forgotten, are similar to those practised by the Polynesians in their old sun-worship.

But whatever their origin, when discovered they were a long way back on the road that all civilizations have travelled—being a simple stone-aged people, fighting nature with stone-age tools and thoughts. In one hundred and fifty years we have hustled them down a long, long road. On a recent Indian grave on a burial island I saw a cooking pot and a rusted boat engine—the owner would need them in the next world. They hang on to the old life with the left hand, and clutch the new life with the right.

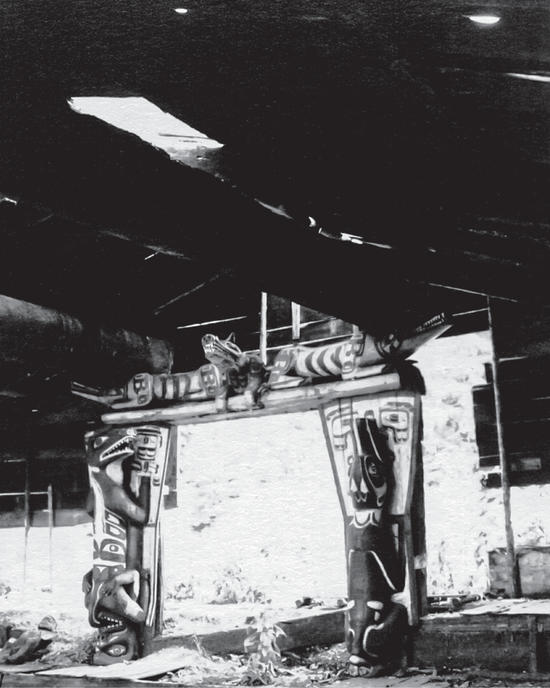

The Indians of the interior called the coast Indians “the peoplewho-live-in-big-houses.” The big house at the end of the village street had lost its roof and walls—only the skeleton remained. Its main uprights or house posts were two great wooden ravens with outstretched wings. Fourteen feet high, wing tip touching wing tip, great beaks and fierce eyes, they stared across to where, some sixty feet away, a couple of killer whales standing on their tails formed a companion pair of posts. A massive cedar log connected each pair across the tops of their heads. At right angles on top of these again, enormous cedar logs ninety feet long and three feet in diameter, all fluted lengthwise like Greek pillars, stretched from one pair to the other, forming with the house posts the main skeleton of the house.

The Nimpkish tribe have a legend that it was the Raven, he who made the first man, who showed them how to get the huge roof-beams in place. It was certainly the first thing we wondered about. When a chief built his house it was a custom for him to kill four of his slaves and bury one under each house post as it was raised—for strength, or good luck, or perhaps prestige. They had a curious habit of destroying their property just to show how great they were.

The house posts tell to which crest the related inmates of the house belong. The crest system runs through all the coast tribes, even among tribes that have a different language and no friendly intercourse. There is the crest of the Raven, of the Grizzly Bear, of the Wolf and others. The reason why each one is related to, or is the ancestor of, a particular family or clan is woven into their folklore. For instance, there is a legend that the killer whale was created a long time after the other animals. He was made by an Indian, whittled out of yellow cedar. The Indian painted him Indian fashion with an extra eye on his stomach; tried him to see if he would float. Then the Indian told him to go and look for food—he might eat anything he found in the water, but he must never touch man. Unfortunately the killer made a mistake. Two Indians were upset out of their canoe and the killer ate them. Ever since then the killer whale has been related to the family of the men he ate and has been used as their crest.

Beat . . . beat . . . beat . . . we laid the nettles low. A cicada shrilled in the midday heat. And somewhere in the tall pines that backed the village a northern raven muttered under its breath. We lifted the long bar from the great door of a community house, and stood hesitating to enter. In the old days a chief would have greeted us when we stepped inside—a sea otter robe over his shoulder, his head sprinkled with white bird down, the peace sign. He would have led us across the upper platform between the house posts, down the steps into the centre well of the house. Then he would have sung us a little song to let us know that we were welcome, while the women around the open fires beat out the rhythm with their sticks. The earth floor would have been covered with clean sand in our honour and cedar-bark mats hastily spread for our sitting. Slaves would have brought us food—perhaps roe nicely rotted and soaked in fish oil, or perhaps with berries. The house would have been crowded with people—men, women, children, and slaves. Three or four fires would have been burning on the earth floor and the house would have been smoky but dry.

We stepped inside and shivered—the house felt cold and damp after the heat outside. Mounds of dead ashes, damp and green, showed where fires had been. A great bumpy toad hopped slowly across the dirt floor. And one of the house posts—a wolf carved in full relief with its head and shoulders turned, snarled an angry welcome. The only light came from the open door behind us and from the smoke-holes in the roof. High above us, resting on the house posts, stretched the two fluted beams that served as ridge poles. From them long boards, hand-split like shakes, sloped down to the outer wall plates. The walls were covered with the same. Standing in the centre of the house we were about three feet below the outside ground level, for warmth in winter, I imagine. The sleeping platform was on the lower level and ran round the entire house; and behind it, three feet higher, was the platform on which they kept their possessions. In the early days each family would have had a certain space on the two platforms allotted to it, partitioned off with hanging mats. It was a collection of related but separate families, under a common roof. But it was not community living. In that land of winter rains and fog it seems a natural solution to the problem of trying to keep dry. In the summer, as they still do, they left the winter village and went off in their dugouts up the rivers and inlets.

Sunlight and darkness; heat and cold; in and out we wandered. All the houses were the same size, the same plan, only the house posts distinguished them. Some were without wall boards, some without roof boards—all were slowly rotting, slowly disintegrating, the remains of a stone age slowly dying . . .

Searching . . . poking . . . digging. We found old horn spoons, wooden spoons, all the same shape. Split a kelp bulb lengthwise, leaving an equal length of split stalk, and you have the shape of the coast Indian spoons. Stone hammers, stone chisels. They might have been used to flute the great beams. And why the flutes? Memories of some half-forgotten art, carried across some forgotten sea? In some of the early work there seems to have been a substitution of wood for stone.

In one of the better preserved houses, evidently still in use, there was a beautifully made dugout turned upside down. The Indians still make these dugouts. They take a cedar log the required length, and by eye alone they adze and shape it—keel, bow, stern. When the outside is finished, they drive in wooden pegs, their length depending on the thickness they want the canoe to be. Then they adze, or burn and chisel out the inside until they work down to the wooden pegs. Then comes the work of shaping the dugout, which at this stage is too narrow and high amidships. They fill it up with water and throw in heated stones until the water boils. The wood is then pliable and easily stretched, and they set in the thwarts—spreading and curving the hull to whatever shape they want. The prows are high and curve forward, the tip often carved. This one had the head of a wolf, ears laid back to the wind.

We played with their old boxes-for-the-dead, trying to see if we could fit in. It is astonishing what you can get into in the knee-chest position. The owners of these are not allowed to use them now, tree burial is forbidden. The boxes were of bent cedar work, peculiar to these coast Indians, I think. They are made of single sheets of cedar about half an inch in thickness, cut to shape. On lines, where they want them to bend, they cut V-grooves on the inside and straight cuts on the outside. Then they wet the grooves to make the wood pliable, and bend the box to shape, just as you would a cardboard candy box. The edges are sewn together with small roots through awl holes made in the wood. That is necessary just at the last side. The covers are separate, made of a single piece of heavier cedar; flat except for the front edge which curves up and out. The boxes are bound with twisted cedar-bark rope—in a peculiar fashion that leaves a loop at each comer to hold on the lid. When an Indian was alive he kept his belongings in his box. When he died, his friends, always of another crest, put him in his box and tied it up in a grave tree.

It was so easy to let the imagination run riot in these surroundings. All round me, grey and dim, surged and wavered the onesof-the-past. I picked up a spearhead; smooth brown stone, ground chisel sharp at the edges—and the men of the tribe crowded close. Naked, blackhaired, their faces daubed with red warpaint, their harsh voices raised in excitement. They were pointing at the beach with their spears—the canoes were ready, they were going on a raid, and they raised their spears and shouted.

“Have you found anything?” called Peter behind me . . . and the fierce crowd quivered, hesitated, and were gone.

“Just a spearhead,” I murmured, waving him away . . . but they, the dim ones, would not come back.

It was harder to imagine the women. Perhaps they were shyer. I could only catch glimpses of them; they would never let me get very close. But later, on a sunny knoll on a bluff beyond the village, I surprised a group of the old ones. They were sitting there teasing wool with their crooked old fingers, their grey heads bent as they worked and gossiped—warming their old bones in the last hours of the sun. Then a squirrel scolded above my head; I started, and it was all spoiled. On the knoll where they had sat I picked up a carved affair—on examination, a crude spindle. The village lay below me, already in the shadows. Beyond, to the west, quiet islands lay in the path of the sun. And all around me, perhaps, the old women held their breath until this strange woman had gone. I wondered, as I left, what they would do without the spindle that I carried in my hand.

I was tired of Indian villages for the moment—slightly bewildered by turning over the centuries, like the careless flip of a page. So I turned away and waded through the shallows with the youngsters towards the high rocky point with the tall trees, near where our boat was anchored. It was low tide, and suddenly beside my bare foot, which I was placing carefully to avoid the barnacles, I saw an old Indian bracelet of twisted copper. The children were soon making little darting noises, and in a short time we had found a dozen of them, caught among the seaweed or lying in crevices at the edge of the cliff. Some, like the first, were made of twisted copper; others of brass were worked with diagonal lines, and others had the deep grooves at each end that tell of the number of sons in a family. I knew that they belonged to a period about one hundred and fifty years ago, when they first got copper and brass from the Spaniards. But personal belongings like that would have been buried with their owners. Suddenly I remembered the old tree-burials, and glanced above my head at the great trees that overhung the water. There, sure enough, swaying in the breeze, hung long strands of cedar-bark rope that had once bound a box-of-the-dead to the upper branches.

Our supper on board was punctuated with cries of, “There’s another box! I see another!”—the whole, still, dark wood, on top of the cliff below which we were anchored, was a burial wood, each moss-hung tree holding its grim burden against the evening sky.

My youngsters are tough, they slept as usual—deep, quiet sleep. I lay awake, lost somewhere down the centuries. Things that I did not understand were abroad in the night; and I had forgotten, or never knew, what charms I should say or what gods I should invoke for protection against them. There were dull lights in the deserted villages. Lights that shimmered and shifted, disappeared and reappeared. Lights that I knew could not be there. I heard the sound of heavy boards being disturbed . . . who is it that treads the village platform? There was a shuffling and scuffing up among the boxes of bones in the trees. Low voices were calling and muttering. Something very confidential was being discussed up in that dark patch.

“Tch . . . tch . . . tch!” said a voice in unbelieving tones. It was repeated in all the trees, on all the branches, from all the boxes. Perhaps they couldn’t believe that we had taken the bracelets—none of their own people would have touched the things-of-thedead.

“Tch . . . tch . . . tch!” evidently somebody was telling them all about it.

“O . . . O . . . O . . . O!” came low choruses, from this tree and that tree—perhaps they did believe it now, and were thinking up curses.

Impossible to explain to them that I was trying to save their Past for them—a reproving chorus of “Tch . . . tch . . . tch!” started up immediately.

“But, really,” I insisted.

“O . . . O . . . O . . . O!” reproved the Dead.

Finally, exhausted, I watched the first faint signs of dawn. There was soon a more definite stirring in the trees, and one by one the great northern ravens left their vigils and flew off with a last mutter. The owls winged their way deeper into the forest and at last the woods were quiet—the dead slept. Overhead, an early seagull floated in the grey light, its wings etched in black and white—a peaceful, friendly thing. Then I, too, slept.

We stayed three days in that village; anchored three nights beneath the trees-of-the-dead. After all, if it were the whispers and echoes of the past we wanted—here they were.

But we left on the fourth day on account of a dog—or rather a kind of dog. There is always the same kind of peculiar silence about all these old villages—it is hard to explain unless you have felt it. I say felt, because that describes it best. Just as you have at some time sensed somebody hiding in a dark room—so these unseen presences in an old village hold their breath to watch you pass. After wandering and digging and sketching there for three days, without seeing a sign of anything living except the ravens and owls, a little brown dog suddenly and silently appeared at my feet. There is only one way of getting into the village—from the water by the beach. The forest behind has no trails and is practically impenetrable. Yet, one minute the dog was not, and then, there it was. I blinked several times and looked awkwardly the other way . . . but when I looked back it was still there.

I spoke to it—but not a sound or movement did it make—it was just softly there. I coaxed, but there was no sign that it had heard. I had a feeling that if I tried to touch it, my hand might pass right through.

Finally, with a horrible prickling sensation in my spine, I left it and went down to the beach. As I reached the dinghy, I glanced over my shoulder to where I had left the dog—it was gone! But as I turned to undo the rope—it was on the beach beside me. Feeling, I am not sure what—apologetic, I think—I offered it a piece of hard-tack. It immediately began to eat it, and I was feeling decidedly more rational when I suddenly realized that it was making no noise over it. The hard-tack was being swallowed with the same strange silence. Hurriedly, I cast off and left. I didn’t look back—I was afraid it mightn’t be there.

Later in the morning I said to John—John had been waiting for me in the dinghy at the time—

“John, about that dog . . .”

“What dog?” interrupted John, busy with a fish-hook.

“That little brown dog that was on the beach.”

“Oh, that!” said John, still very busy. “That wasn’t a usual dog.”

I left it at that—that was what I had wanted to know.