Mike

The first time we met Mike must have been the very first time we anchored in Melanie Cove. It was blowing a heavy southeaster outside, so we had turned into Desolation Sound and run right up to the eastern end. There the chart showed some small coves called Prideaux Haven. The inner one, Melanie Cove, turned out to be wonderful shelter in any wind.

We anchored over against a long island with a shelving rock shore. The children tumbled into the dinghy and rowed ashore to collect wood for the evening bonfire, while I started the supper. Away in at the end of the cove we could see what appeared to be fruit trees of some kind, climbing up a side hill. It was in August, and our mouths started watering at the thought of green apple sauce and dumplings. There was no sign of a house of any kind, no smoke. It might even be a deserted orchard. After supper we would go in and reconnoitre.

We were just finishing our supper when a boat came out of the end of the cove with a man standing up rowing—facing the bow and pushing forward on the oars. He was dressed in the usual logger’s outfit—heavy grey woollen undershirt above, heavy black trousers tucked into high leather boots. As I looked at him when he came closer, Don Quixote came to mind at once. High pointed forehead and mild blue eyes, a fine long nose that wandered down his face, and a regular Don Quixote moustache that drooped down at the ends. When he pulled alongside we could see the cruel scar that cut in a straight line from the bridge of his nose—down the nose inside the flare of the right nostril, and down to the lip.

“Well, well, well,” said the old man—putting his open hand over his face just below the eyes, and drawing it down over his nose and mouth, closing it off the end of his chin—a gesture I got to know so well in the summers to come.

“One, two, three, four, five,” he counted, looking at the children.

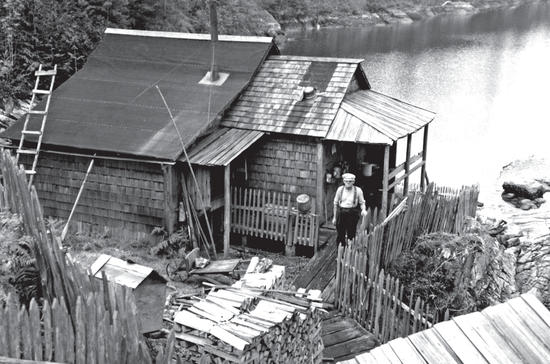

He wouldn’t come aboard, but he asked us to come ashore after supper and pick some apples; there were lots of windfalls. We could move the boat farther into the cove, but not beyond the green copper stain on the cliff. Later, I tossed a couple of magazines in the dinghy and we rowed towards where we had seen him disappear. We identified the copper stain for future use, rounded a small sheltering island, and there, almost out of sight up the bank, stood a little cabin—covered with honeysuckle and surrounded by flowers and apple trees. We walked with him along the paths, underneath the overhanging apple-branches. He seemed to know just when each tree had been planted, and I gathered that it had been a slow process over the long years he had lived there.

Except for down at the far end, where the little trellis-covered bridge dripped with grapes, the land all sloped steeply from the sea and up the hillside to the forest. Near the cabin he had terraced it all—stone-walled, and flower-bordered. Old-fashioned flowers—mignonette and sweet-williams, bleeding-hearts and bachelor’s buttons. These must have reached back into some past of long ago, of which at that time I knew nothing. But beauty, which had certainly been achieved, was not the first purpose of the terraces—the first purpose was apple trees.

He had made one terrace behind the house first—piled stones, carted seaweed and earth until he had enough soil for the first trees. From there, everything had just gradually grown. Down at the far end, where terraces were not necessary, the trees marched up the hillside in rows to where the eight-foot sapling fence surrounded the whole place. “The deer jump anything lower,” said Mike, when I commented on the amount of time and work it must have taken. Then he added, “Time doesn’t mean anything to me. I just work along with nature, and in time it is finished.”

Mike sent the children off to gather windfalls—all they could find—while he showed me his cabin. There was a bookshelf full of books across one end of the main room, and an old leather chair. A muddle of stove, dishpan and pots at the other end, and a table. Then down three steps into his winter living-room, half below ground level. “Warmer in winter,” he explained. He saw us down to the boat, and accepted the two magazines. Then he went back to the cabin to get a book for me, which he said I might like to read if I were going to be in the cove for a few days.

“Stoort sent it to me for Christmas,” he said. I felt that I should have known who Stoort was. I couldn’t see the title, but I thanked him. The children were laden with apples—and full of them, I was sure.

Back in the boat, I looked at the book by flashlight. It was Why be a Mud Turtle, by Stewart Edward White. I looked inside—on the fly-leaf was written, “To my old friend Andrew Shuttler, who most emphatically is not a mud turtle.”

During the next couple of days I spent a lot of time talking to old Mike, or Andrew Shuttler—vouched for by Stewart Edward White as being, most emphatically, worth talking to. The children were happy swimming in the warm water, eating apples, and picking boxes of windfalls for Mike to take over to the logging camp at Deep Bay.

In between admiring everything he showed me around the place—I gradually heard the story of some of his past, and how he first came to Melanie Cove. He had been born back in Michigan in the States. After very little schooling he had left school to go to work. When he was big enough he had worked in the Michigan woods as a logger—a hard, rough life. I don’t know when, or how, he happened to come to British Columbia. But here again, he had worked up the coast as a logger.

“We were a wild, bad crowd,” mused Mike—looking back at his old life, a far-away look in his blue eyes. Then he told of the fight he had had with another logger.

“He was out to get me . . . I didn’t have much chance.”

The fellow had left him for dead, lying in a pool of his own blood. Mike wasn’t sure how long he had lain there—out cold. But the blood-soaked mattress had been all fly-blown when he came to.

“So it must have been quite some few days.”

He had dragged himself over to a pail of water in the corner of the shack and drunk the whole pailful . . . then lapsed back into unconsciousness. Lying there by himself—slowly recovering.

“I decided then,” said Mike, “that if that was all there was to life, it wasn’t worth living; and I was going off somewhere by myself to think it out.”

So he had bought or probably pre-empted wild little Melanie Cove—isolated by 7,000-foot mountains to the north and east, and only accessible by boat. Well, he hadn’t wanted neighbours, and everything else he needed was there. Some good alder bottom-land and a stream, and a sheltered harbour. And best of all to a logger, the southeast side of the cove rose steeply, to perhaps eight hundred feet, and was covered with virgin timber. So there, off Desolation Sound, Mike had built himself a cabin, handlogged and sold his timber—and thought about life . . .

He had been living there for over thirty years when we first blew into the cove. And we must have known him for seven or eight years before he died. He had started planting the apple trees years before—as soon as he had realized that neither the trees nor his strength would last forever. He had built the terraces, carted the earth, fed and hand-reared them. That one beside the cabin door—a man had come ashore from a boat with a pocket full of apples. Mike had liked the flavour, and heeled in his core beside the steps.

“Took a bit of nursing for a few years,” said Mike. “Now, look at it. Almost crowding me out.”

He took us up the mountain one day to where he had cut some of the timber in the early days, and to show us the huge stumps. He explained how one man alone could saw the trees by rigging up what he called a “spring” to hold the other end of the saw against the cut. And how if done properly, the big tree would drop onto the smaller trees you had felled to serve as skids, and would slide down the slope at a speed that sent it shooting out into the cove. He could remember the length of some of them, and how they had been bought for the big drydock down in Vancouver.

I got to know what books he had in the cabin. Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, Plato, Emerson, among many others. Somebody had talked to him, over the years, and sent him books to help him in his search. He didn’t hold with religion, but he read and thought and argued with everything he read. One summer I had on board a book by an East Indian mystic—a book much read down in the States. I didn’t like it—it was much too materialistic to my way of thinking, using spiritual ways for material ends. I gave it to Mike to read, not saying what I thought of it, and wondered what he would make of it. He sat in his easy chair out underneath an apple tree, reading for hour after hour . . . while I lay on the rocks watching the children swim, and reading one of his books.

He handed it back the next day—evidently a little embarrassed in case I might have liked it. He drew his hand down and over his face, hesitated . . . Then:

“Just so much dope,” he said apologetically. “All words—not how to think or how to live, but how to get things with no effort!”

I don’t think anyone could have summed up that book better than the logger from Michigan.

Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s—he loved them. I would leave him a pile of them. At the end of the summer, when we called in again, he would discuss all the articles with zest and intelligence.

Mike’s own Credo, as he called it, was simple. He had printed it in pencil on a piece of cardboard, and had it hanging on his wall. He had probably copied it word for word from some book—because it expressed for him how he had learnt to think and live. I put it down here exactly as he had it.

“Look well of to-day—for it is the Life of Life. In its brief course lie all the variations and realities of your life—the bliss of growth, the glory of action, the splendour of beauty. For yesterday is but a dream, and To-morrow a vision. But To-day well lived makes every Yesterday a dream of happiness, and every To-morrow a vision of hope. For Time is but a scene in the eternal drama. So, look well of to-day, and let that be your resolution as you awake each morning and salute the New Dawn. Each day is born by the recurring miracle of Dawn, and each night reveals the celestial harmony of the stars. Seek not death in error of your life, and pull not upon yourself destruction by the work of your hands.”

That was just exactly how Mike lived—day by day, working with nature. That was really how he had recovered from the fight years ago. And later how he had pitted the strength of one man against the huge trees—seven and eight feet in diameter and two hundred or more feet high. Just the right undercut; just the right angle of the saw; just the right spots to drive in the wedges—using nature as his partner. And if sometimes both he and nature failed, there was always the jack—a logger’s jack of enormous size and strength that could edge a huge log the last critical inches to start the skid.

He lent his books to anyone who would read them, but the field was small. For a time there was a logging outfit in Deep Bay, three miles away. They used to buy his vegetables and fruit. Some of them borrowed his books. He talked and tried to explain some of his ideas to the old Frenchman in Laura Cove—old Phil Lavine, who was supposed to have killed a man back in Quebec. After Mike was dead, old Phil commented to me, almost with satisfaction, “All dem words, and ’e ’ad to die like all de rest of us!”

But the next year when we called in to see him, old Phil had built book-shelves on his wall—around and above his bunk, and on the shelves were all Mike’s books. Phil was standing there proudly, thumbs hooked in his braces, while some people off a yacht looked at the titles and commented on his collection . . . Phil the savant—Phil who could neither read nor write.

Among Mike’s circle of friends—lumbermen, trappers, fishermen, people from passing boats that anchored in the cove—not many of them would have stayed long enough, or been able to appreciate the fine mind old Mike had developed for himself. And the philosophy he had acquired from all he had read in his search to find something that made life worth living.

I can’t remember from whom I heard that Mike had died during the winter. When we anchored there the next year, the cove rang like an empty seashell. A great northern raven, which can carry on a conversation with all the intonations of the human voice, flew out from above the cabin, excitedly croaking, “Mike’s dead! Mike’s dead!” All the cliffs repeated it, and bandied it about.

The cabin had been stripped of everything—only a rusty stove and a litter of letters and cards on the floor. I picked up a card. On the back was written, “Apple time is here again, and thoughts of ripe apples just naturally make us think of philosophy and you.” It was signed, “Betty Stewart Edward White.”

Apple time was almost here again now, and the trees were laden. But apples alone were not enough for us. We needed old Mike to pull his hand down over his face in the old gesture, and to hear his—“Well, well, well! Summer’s here, and here you are again!”