“Capi” Blanchet

Originally Published in Raincoast Chronicles 8

One of the most insightful and best-researched character studies of M. Wylie Blanchet was written by journalist Edith Iglauer and published in the eighth issue of the West Coast journal Raincoast Chronicles (1979). Readers should keep in mind this essay was written over forty years ago when many of Capi Blanchet’s friends and children were still living. Ms. Iglauer interviewed every one of them she could.

When I came to live on the British Columbia coast I was given as a sort of spiritual introduction a remarkable little volume entitled The Curve of Time by M. Wylie Blanchet. The book was a particularly appropriate choice; my summers were spent on a fishing boat, the Morekelp, with my husband John Daly, a commercial salmon troller, and the area he regularly traversed partly followed the path travelled by Mrs. Blanchet and her five children on their tiny motor launch, the Caprice.

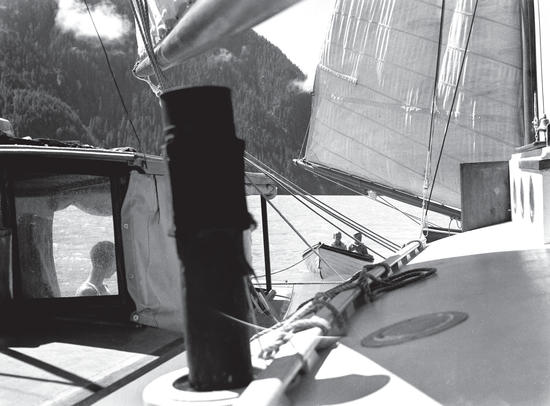

The five Blanchet youngsters, led by their indomitable mother, spent four summer months for fifteen years—the older ones less time as other commitments pressed in—on a twenty-five by six-and-a-half foot boat made of half-inch cedar, travelling around the west coast of Vancouver Island and as far north up the Inside Passage as Cape Caution. They explored the inlets and bays, sometimes following the trail broken by that earlier intrepid mariner Captain George Vancouver, with whom they felt a great empathy; their experiences finally written down in a series of sketches that encompassed all the years of their journeys as if they were one. The title The Curve of Time refers to the capacity of any one of us to stand on the highest curve of the Present in Time and look back into the Past, forward into the Future or to wander at will from one to the other. Which is precisely what M. Wylie Blanchet did in this brief account that has triumphed over Time to become one of the classics in British Columbia literature. It is M. Wylie Blanchet’s only book, originally published in 1961 when she was seventy years old.* That same year she died of a heart attack, sitting at her desk where she was found slumped over her typewriter. She had lived just long enough to enjoy being a published author with a small reading public that wrote her admiring letters.

M. Wylie Blanchet. At first, she tried using just “M. Wylie.” M. was for Muriel, the author’s given name, which she hated; Wylie was borrowed from a grandparent; and Blanchet was acquired by marriage. Altogether it was the impersonal sound hat she intended: she hoped the author would not be recognized by the people up the coast about whom she was writing, who knew her simply as “Capi” Blanchet. As to the nickname—wasn’t she the Captain of the Caprice?

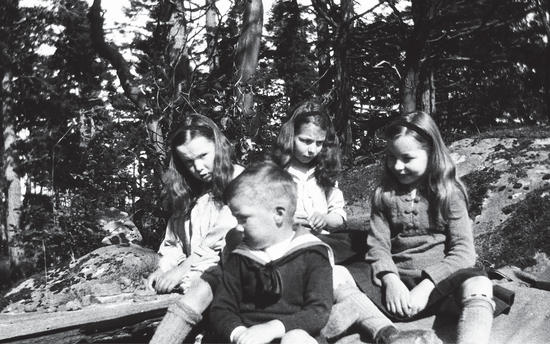

In the last chapter of the book, entitled “Little House,” Mrs. Blanchet comes off the Caprice to write about the family’s land base on seven secluded acres of Vancouver Island’s coast, from which they returned in October. For an ordinary family this would have meant cutting two months from the school year, but the Blanchet children received their early education at home under their mother’s guidance. In the first edition of the book, Mrs. Blanchet confined herself in this final chapter to a poetical narrative evoking the wild and beautiful setting of Little House. Later editions include the beginning of a second unfinished manuscript and mysterious shadows, with the suggestion of personal tragedy in a cryptic statement, “the legacy of death often shapes our lives in ways we could not imagine.” The Curve of Time manages to be sentimental, imaginative, and often strays into whimsy, but it is reticent about hard facts; it reads like an impressionist painting. Its characters, whose physical appearances are never really described, are shadowy figures against the lush and brilliant scenery of the British Columbia coast. We know what they do and how they feel but not what they look like or who they are other than a mother and five children, three girls and two boys, the youngest around three at the time Mrs. Blanchet chose to locate her story.

Despite the reticence we do know the important things about this remarkable woman. She comes through as extremely courageous, innovative and as a kind of mechanical wizard compared to most women. Without formal training or experience she could make an engine that failed at an isolated anchorage start chugging again. She could steer a small craft over shoals, through narrows and rapids, read charts correctly and arrive where she intended to be, while she was providing food, proper shelter from whatever winds were prevailing and adventure for her children. Yet readers close her book with a scratchy feeling of curiosity. Who was M. Wylie Blanchet? What was she like?

Her Canadian publisher Gray Campbell, a fellow British Columbian who was both neighbour and friend, has described her as having “a delightful shyness,” as a serious person with “a delicious, dry sense of humour.” Campbell first became acquainted with her when the Caprice was berthed next to his boat at Canoe Cove, a short distance from the Blanchet house, which was five miles from Sydney. He too was writing, and Capi Blanchet used to sit in the cabin of his boat and read the chapters of his uncompleted manuscript. He has said since that it was the lack of success of the first edition of The Curve of Time, whose English publisher never bothered to see that it was stocked in bookstores either in Victoria or Vancouver, that helped to convince him that there was a need for regional publishing. Only six or seven hundred copies even got as far as Toronto. The author had to loan a local bookstore the money to get copies of her own book for her friends.

Muriel Blanchet was born Muriel Liffiton in 1891 in Lachine, Quebec, into a well-to-do family with High Anglican principles. The Liffitons were English but the Snetsingers, on her mother’s side, were pre-Revolution Dutch settlers in the Hudson Valley. They crossed the border into Canada during the American Revolution, settling in the St. Lawrence valley with a land grant well located downstream from the town of Cornwall. Grandfather Snetsinger was a warden of Cornwall and Member of Parliament for the area, and left a considerable inheritance whose final distribution was made only a year ago. The ancestral home is now under sixty feet of St. Lawrence river water and all the original land has been sold.

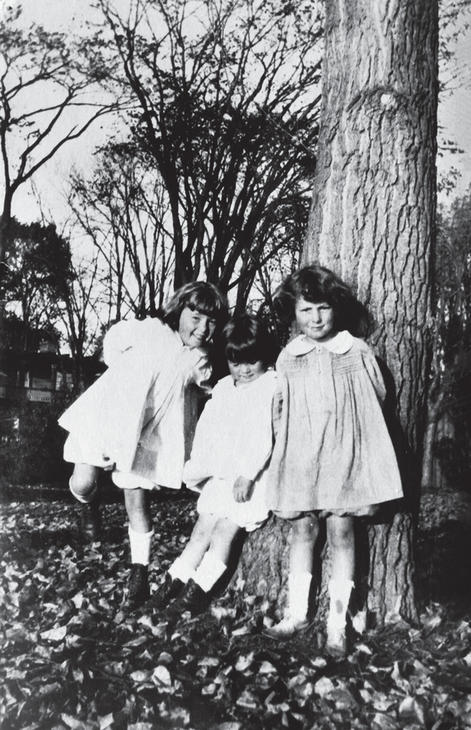

Muriel was the middle one of three sisters and something of a tomboy. She customarily carried squirrels and mice around in her pockets, to the horror of the girls’ tutor, described as “a kind of retired clergyman.” Their father was a prosperous customs broker who announced from time to time at breakfast that he was departing and would then disappear for a year or so. The only hint of his whereabouts would be a casual remark later when he helped his daughters with their geography lessons, that he had just been in Alexandria, Egypt, or once, in Timbuctoo. Later he sent the three girls to St. Paul’s private school for girls near Montreal, where Muriel developed a strong sense of competition with her sister Violet, five years older and a prize-winning scholar. Muriel set out to surpass her in the same determined manner with which she later approached the mysteries of the gasoline engine. The results of this four-year scholastic campaign are still evident in a row of small red leather Temple volumes of Shakespeare in the library of Mrs. Blanchet’s youngest son David (called John in the book). Each volume was given her as a prize for top honours in a different subject, and she never stopped until she had the whole set, inscribed in Muriel Liffiton in the heavy black script of R. Newton, Rector of St. Paul’s, and bearing the motto Non Sans Droit with the school’s coat of arms. Between 1905 and 1908 Muriel Liffiton repeatedly captured first prizes in Latin, French, spelling, astronomy, history, geography, geometry (Euclid), algebra and English, beginning with a modest two her first year and winding up with six at graduation. One year she was awarded a special prize (Antony and Cleopatra) for top excellence in “All Subjects.” Her older sister Violet, known in the family as “Auntie Teake,” subsequently married a banker, was widowed, and at ninety-six lives in a nursing home in Windsor, Ontario. Until very recently she still continued a lifelong habit of writing letters all night to the family. The youngest sister Doris, remembered by her nieces and nephews for her charm and erudition, studied at Oxford and the University of Rome, converted to Catholicism and became a nun, entering the Order of the Sacred Heart. When she was Mother Superior of the Sacred Heart Convent on Point Grey Road in Vancouver the two oldest Blanchet girls, Elizabeth and Frances, attended high school there for two years.

With a scholastic record like hers Muriel Liffiton was expected to go on to university but instead at eighteen she married Geoffrey Blanchet, the brother of a school friend—a decision she is said to have regretted later. The first Blanchet in North America arrived from France in 1666 but Geoffrey, although bilingual, was only about one-sixth French. He was from Ottawa, the youngest of eleven children, and his father was a minor civil servant.

Geoffrey and Muriel Blanchet started married life in Sherbrooke, Quebec, where he was a bank manager. Later he was placed in charge of foreign exchange at the Toronto headquarters of the Bank of Commerce. He was a clever, somewhat artistic man with a highly emotional, nervous temperament. In his early forties he became ill and took early retirement. The family by that time included four children, and when he had sufficiently recovered he packed them all into a Willys-Knight touring car which, according to one of the children, “had flapping curtains and a great top that folded like an elephant sitting down,” and started driving across the country looking for an island to live on. They drove and drove until they came to Chicago, where the Blanchets parked their car on a city street while they all slept. David had not been born yet and Peter, then aged three-and-a-half, remembers sleeping in a hammock strung from the roof of the Willys-Knight. A policeman woke them up and they continued across Canada and the States until they came to Vancouver Island.

Peter Blanchet, whom the family calls by his middle name, Tate, is now a grey-haired geological engineer in his late fifties. Sitting in his office in Vancouver, he can still remember clearly how they found their new home. “We came to a locked gate with Clovelly written on it, got out of the Willys-Knight, climbed the gate and had supper on the other side,” he recalled. “Intrigued, we packed the gate off its hinges and drove a quarter of a mile to a house built of log slabs with the bark still on it.” Clovelly, named by a previous owner after a place in Cornwall, became Little House, purchased by the Blanchets in 1922. It had been empty since 1914, part of a one-hundred-acre real estate scheme that collapsed during World War I. The Blanchets were able to buy seven acres at the extreme tip, Curteis point, overlooking the Gulf of Georgia, and they kept it until Mrs. Blanchet died in 1961, although Little House was torn down in 1948. It was an unusual house, a strangely mystical English cottage covered with ivy, with a big fireplace and a billiard table on the first floor and four bedrooms up a rickety flight of stairs on the second floor. “It was designed by a celebrated architect, Sam McLure, and built by a crook,” said David Blanchet, who was born there. “It was a beautiful design on wretched foundations and full of dry rot.” By the time he and his mother tore it down after World War II the foundations were so far gone that the house had a tremendous list and dining room chairs were sliding every which way.

Their boat the Caprice was purchased in 1923 for six hundred dollars. It had been built the year before, a cold year and the Brentwood Ferry, near which it was anchored, managed to shove a cake of ice into the side of the Caprice, sinking it. It was hauled out on a nearby dock and the Blanchets bought it on the spot, with water still dribbling out of it. “This was probably when my mother learned to deal with engines,” David has commented. “It had to be cleaned out immediately, once it had been in salt water. We had that same engine for twenty years, until it was changed in 1942.”

Peter Blanchet remembers the first time his mother took the Caprice out on her own. It was in March, on his sixth birthday, and she had promised to take him to Shell Island, a favourite spot where she liked to say she would spend her hundredth birthday. She and Peter got in the boat, which they kept at Canoe Cove, and “she cranked and cranked that darned engine, and still it wouldn’t start,” Peter recalled. “She could see my father sitting on the Point watching to see if we would get off and she had to go and get him, which really irked her. Then she and I went fishing for the day off Sidney Spit. We caught a couple of fish which we cooked over a fire on the beach at Shell Island. It was very good salmon!”

Geoffrey Blanchet died in 1927. He had gone off on the Caprice by himself for the day, stopping at nearby Knapp Island, where he anchored and set up his cookstove. He was never seen again, but his boat was found by a Chinese gardener working for the Harvey family, who lived on the island. Blanchet had had heart problems and was presumed to have gone for a swim, had an attack and drowned.

The second summer after his death, Mrs. Blanchet rented Little House and took the children off on the Caprice for the first of the venturesome trips that as a composite memory became the substance of The Curve of Time. With the money she received from renting Clovelly in summer to a wealthy family from Washington and her own small income, she was able to manage. The two oldest girls, Elizabeth and Frances, missed several summers on the boat when they were sent east to live with an aunt and uncle on their father’s side in Ottawa; and later when they went to the convent in Vancouver, their holidays were shorter, eventually shrinking to two weeks when they both studied nursing. Elizabeth started nursing on the BC coast, married and went to England, where she still lives. She became a freelance journalist and the successful author of over thirty published books. Her mother’s attitude towards her writing was a mixture of pride and a tendency to regard her daughter’s books as pot-boilers. Most of them are novels with a documentary background, often based on Elizabeth’s hospital experiences, and many are still selling. Frances married two years after she started nursing, and she and her husband, Ron King, raise Hereford cattle on their ranch near Golden, BC.

The three younger children, Joan, Peter and David, were educated almost entirely at home, by correspondence, by their mother, and by a Scottish engineer who was a mechanic at the Canoe Cove boat works, who taught them math, chemistry and physics. Joan, known as the rebellious member of the family, went to art school in Vancouver and then continued her art studies in New York. When she left Vancouver, she bought an old Indian dugout canoe for five dollars and paddled home. It took her five days, and she crossed the Gulf of Georgia at night, to avoid traffic and heavy seas, a remarkable feat since it required at least nine hours of steady paddling. Frances King vividly recalled hearing about her sister’s arrival. “When she rounded the point in her dugout, wearing an old red sweater, Capi and the boys were sitting on the bluff, wondering who the Indian was! Joan had expected some commendation, and was amazed at Capi’s anger. ‘Just because I’m a fool doesn’t mean you children have to be!’” Capi said. Later the boys reported that Capi laughed herself to sleep. Joan later confided to a friend that she was testing herself; she felt if she could cross the Gulf of Georgia alone, she would have the confidence to face New York. She subsequently married Ted McFeely, from whom she is now divorced and lives in a remote spot on the already remote Queen Charlotte Islands.

Peter, who had an inventive mind and was working on a memory rod before he ever heard of computers, entered the University of British Columbia at sixteen, and managed one more summer on the boat before the pressures of adult life took him away. David, who inherited his mother’s imaginative sensitivity, after one year in a local school and a year in university joined the army when the Second World War began. After the war he returned to Little House, which by now was literally falling apart. He and his mother proceeded to tear it down, starting at the top, and together they designed and built her an attractive white bungalow directly overlooking the sea. David went on to construct another house for a friend and began one for himself, meanwhile returning to university to study architecture. By then he was married to Janet Patterson, a handsome woman of great character and the daughter of writer R.M. Patterson. They had one child, Julia, and when she was four David was stricken with poliomyelitis, which left him partially paralyzed, confined to a wheelchair. They live now in North Vancouver.

In appearance, Capi Blanchet was of medium height, with very fine blonde hair brushed upwards so that it formed a kind of haze around her head. She had a strong rather than a pretty face, round and pleasant. Her normal attire was a pair of khaki shorts, a Cowichan sweater and sneakers that sometimes had holes in the toes. She had begun wearing shorts in the nineteen-twenties, long before they were fashionable, and her daughter Elizabeth has recalled that a journalist writing about people he had met on the BC coast in The Saturday Evening Post “commented on her shorts and how suitable they seemed for what she was doing—running a boat.” In 1957 Capi went to England to visit Elizabeth, bought a Land Rover, and the two women went camping. “We were shopping in Chartres, France, and she was wearing blue jeans, clamdigger length,” Betty said. “A white-haired Frenchman walked slowly around her, smiled and bowed. ‘Très chic, Madame!’ was his comment.” What impressed Mrs. Blanchet however on her trip was the lack of wood on the beaches, since this was her main source for firewood at home.

Mrs. Blanchet’s children and friends were enormously fond of her, somewhat in awe of her all-round competence, and thought her fair-minded but domineering. “She was a challenge for any child, but slightly dampening,” her eldest daughter has written. “She could do almost anything that men did, and still be feminine.”

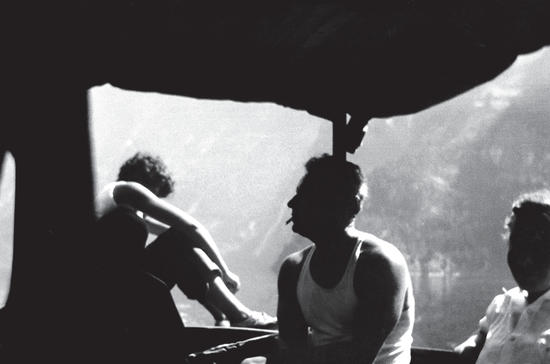

“She had a lot of courage and self confidence, but she did not over estimate her mechanical ability,” a writer friend, Hubert Evans, has said. “On a run from Sidney to Vancouver, the Caprice was overtaken in the Gulf by a late season southeaster, and the little boat took quite a dusting,” he related. “Capi had several children aboard. ‘I told the Lord I could take care of the boat but would he please keep the engine running,’ she said to me afterwards.”

Capi Blanchet does not seem to have been particularly light-hearted or spontaneous, and she was somewhat arrogant about anyone she considered her inferior. “Like many English of a certain class she had a stiffness and tended to classify people,” another friend has remarked. “She had a slightly Church-of-England attitude, even talking to fishermen, who were never sure how to take her. She had a good sense of humour but a rather studied laugh. I think there was a good deal of repression there. Even when David was desperately ill she never permitted anyone to see her upset, and said to her daughter-in-law, ‘Oh heck, he’ll get better in no time!’”

A description from her daughter Frances exemplifies the quality of character her children and friends remember best: “She was capable of handling any situation. If she was worried she didn’t let us know.”

On the boat Mrs. Blanchet was even-tempered under what must often have been trying conditions at such close quarters; her method of discipline was to separate her children, not argue. David remembered his mother losing her temper with him only once, when he was about twelve. “It was some silly mistake, something about an anchor, that I did my way instead of what she wanted,” he said. “Normally her eyes were brown, but suddenly they were a turquoise colour and blazing. It was unbelievable!”

She was one of those rare women who are mechanically inclined, and enjoyed tinkering with engines and working with tools. Every so often she took apart the Caprice engine, a four-cylinder Kermath, cleaned and painted it and put it back together again, grinding the valves herself. Frances King remembers the first time she took her husband to meet her mother. The morning after their arrival he found Capi in her workshop. She had taken the old engine out of the Caprice, had ground the valves and was putting in new rings and checking the timing. “Having worked in a garage, Ron could appreciate with amazement what his mother-in-law was doing, whereas this was everyday stuff to me,” Frances said.

An intimate friend of Mrs. Blanchet’s, Kathleen Caldwell, has described her as “not excessively domestic, but interested in people and politics, which she loved to discuss. Her house was comfortable and pleasant, and Capi could produce a beautiful meal with what looked like no effort.” In their close circle Capi was renowned for her roast beef, Yorkshire pudding and mouth-watering pastry. Oddly enough, although she liked to eat fish, she never cooked it except outdoors on a beach because she couldn’t stand the smell.

Mrs. Blanchet liked to draw sea creatures in pen and ink, and once illustrated a fairy story she wrote with drawings in the margin. She was also a fair pianist, and in later life enjoyed playing a violin that her grandfather gave her when she was twelve. It now hangs on the wall of David’s living room, but his mother used it often; she had joined a small orchestra at Deep Cove, playing second violin, reputedly a quarter-tone flat.

Children found her very understanding. She treated them like adults, and when David contracted polio she took care of their daughter Julia for two years while he was in hospital in Vancouver and Victoria and his wife Janet worked. Grandmother and grandchild got on very well, and it was a mutually beneficial relationship; by then Capi had become somewhat reclusive—having Julia with her forced her to go out.

David fell ill before the interior of Mrs. Blanchet’s new house was completed and it never seemed to advance beyond that half-built stage. She lined the whole interior with vertical cedar planks herself, but doors were a late addition to the bathroom and kitchen and knobs usually came off in hand. Her firewood was never quite dry and Kathleen Caldwell once delighted her by bringing a gift of Presto logs. When Capi’s doctor prescribed a drier climate for a cough that later developed into emphysema she ignored him and instead sat with her head as far into her oil stove as she could get it for twenty minutes a day. “That’s my high, dry climate,” she said. She had an ingenious system of heating water in the morning before she was ready to light the oil stove. She turned an electric iron upside down, supported it with stones, set it at its highest heat, put a pan on top of it and boiled her water for breakfast there.

As for the Caprice, it was never meant to have any other owner than Capi Blanchet. After the war she planned to build a new boat and sold the Caprice for seven hundred dollars—a hundred more than she had paid for it—to the owner of a boat works in Victoria, who hauled it up for repairs. While it was on the ways the entire boat works burned down, including the Caprice. Mrs. Blanchet did have another boat after that, the Scylla, but she never really used it.

Mrs. Blanchet’s children, now older than she was when they made their wonderful odysseys along the coast, look back on that faraway time with wonderment and affection. “They were exciting; something we looked forward to,” Peter commented. “It was a fairly normal life for us, however, because we always seemed to be doing it.”

“I loved the summer journeys but I doubt if any of us appreciated quite how unique our childhood was. We just knew Capi was doing something unusual,” Elizabeth writes from England. “She used to get a bit tense if we were taking green water over the bow or wallowing about in a following sea or running the Yaculta Rapids. Otherwise she took everything in her stride—whether crossing the Straits of Georgia at 4 a.m. to beat the sou’wester or exploring new territory.”

“Only fools seek adventures,” David has remembered his mother as saying at one time or another. However foolish Mrs. Blanchet’s adventures may have seemed to her (which is doubtful), they have a dreamlike charm for an increasing number of readers. The Curve of Time has had a separate and ongoing life of its own, achieving its own small immortality.

- * Publisher’s note: Blanchet’s book for children, A Whale Named Henry, was published posthumously by Harbour Publishing in 1983.