Chapter Four: “If you go in blind you will come out skinned”

Throughout the spring and summer of 1858, the Black emigrants left San Francisco. They were only a fraction of the adventurers travelling north; the new gold rush seemed to be depopulating the Bay Area. Some San Franciscans even feared that their city would lose its economic supremacy to Victoria.

“San Francisco,” the Daily Evening Bulletin observed in June, “is running wild with excitement.” Everyone wanted news from the north. The Bulletin printed a map of the Fraser River several times, as well as a glossary of Chinook Jargon, the trade language of the Northwest.

“The Pacific Mail Steamship office was this morning completely besieged with applicants for tickets to Frazer River. The American Exchange and Wharf House are running over. The house of J.M. Strobridge, the great head-quarters of the Clothing trade, presented the busiest scene of all.” So ran one account. The Bulletin sounded almost plaintive when it editorialized: “It is to be hoped that our people will not permit themselves to become so completely absorbed in Frazer River speculations as to suffer the approaching Fair of the State Agricultural Society to pass thinly attended.”

Nevertheless, the San Francisco papers did their best to distract their readers from everything but the gold rush.

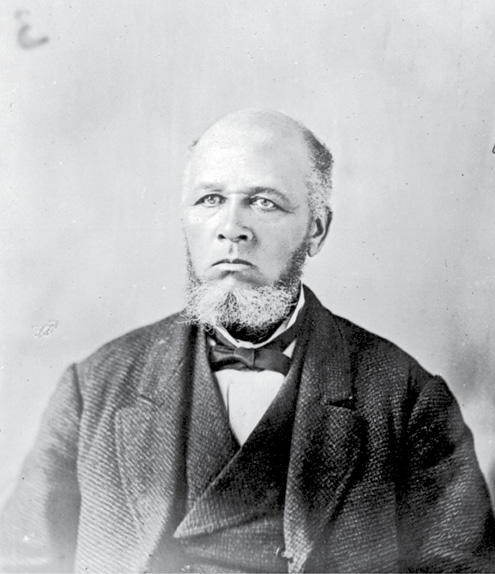

Mifflin Gibbs wasn’t with the first contingent on the Commodore, but he was quick to understand the opportunities the gold rush offered. In his autobiography, he recalled his own journey north: “In June of that year, with a large invoice of miners’ outfits, consisting of flour, bacon, blankets, picks, shovels, etc., I took passage on steamship Republic for Victoria.” Some seven hundred passengers were aboard, an indication of the size of the rush.

He went into business almost the moment he stepped ashore, and found time to write a long letter that was published in the Bulletin on June 23:

"Victoria, V.I., June 16, 1858

Friend L [probably Peter Lester]:—You will now see that I have arrived at my point of destination. I came, however, rather late to make the most advantageous investments. The country is certainly a beautiful one—a country good enough for me—and I am sorry we are so far behind. If either of us had arrived here two months ago, worth $1,000, we could have been worth $10,000 today. As it is, I arrived here (or on land) on Saturday, 12th June, and the Land Office closed on Friday, for ten days, completely shutting off all purchasers for that time. I went to the office, and was introduced to the officers. They informed me that they would give public notice when the office opened, and I would have a fair chance. The lots have been selling at $50, but when the office opens I understand they will be $100. They said they had to close in order to regulate matters, as the lots were being sold faster than they could be surveyed, and would get confused. On the last day, the office was literally besieged. They took some forty or fifty thousand dollars.

I have been terribly bothered and almost bewildered, not knowing how to act. There are a number of lots in the hands of half-a-dozen speculators, who are holding them at exorbitant rates. Lots in the most desirable portion of the town at this time, which could have been bought from the Land Office, three months ago, for $50, and from settlers here for from $300 to $700, they are now asking, and getting, from $1,500 to $5,000 for. A lot sold since I have been here (three days) for $5,000, has again changed hands for $6,200. Everybody is excited; but I think that real estate is as high as it can safely be. It will undoubtedly go higher, but will first recede to await the immigration of actual settlers. The fact is, there is the greatest possible demand for houses, both to live and do business in, in the business portion of the town. Men are walking around, begging for a place to live and do business in. All the lots are sold to within four squares of the business quarter, and further, I guess.

The business portion here is generally owned by old fogies, who are destitute of Yankee enterprise. They are afraid to lease, for fear they will regret it; and ask such prices that parties who have the means are afraid to buy. Add to this that you cannot purchase a piece of lumber in the place, that houses half-way in the process of erection are standing idle, and that there are no sloops or scows in the harbor to go after it. A great many miners, who are waiting here for the river to fall, have camped around the tents. Lumber here would now fetch $60 to $100 a thousand. I have not had my clothes off nor had a bed to lie on, since I left San Francisco. I thought I would have broke down the first day or two, not having had a night’s comfortable rest since I left. Then landing in a whirlpool of excitement! But I am feeling better now, and am getting pretty thoroughly posted on land points and speculators, and that is worth considerable, for if you go in blind you will come out skinned. . . . I have said nothing about the mines, as people here have ceased to ask any questions on that point; their permanency and richness are undoubted by all who arrive from them.

"

Gibbs’s letter conveys the feverish mood of Victoria in its first boom. A small, quiet hamlet, it had been staggered by huge numbers of newcomers, most of them transients. One who came to stay, Alfred Waddington, described the shock in his book The Fraser Mines Vindicated (the first book published in Victoria).

Before the rush, he wrote, Victoria had been a backwater: “No noise, no bustle, no gamblers or speculators or interested parties to preach up this or underrate that. A few quiet gentlemanly behaved inhabitants, chiefly Scotchmen, secluded as it were from the whole world. . . . As to business there was none, the streets were grown over with grass, and there was not even a cart.”

Waddington confirmed Gibbs’s first impressions of the influx of miners:

"This immigration was so sudden, that people had to spend their nights in the streets or bushes, according to choice, for there were no hotels sufficient to receive them. Victoria had at last been discovered, everybody was bound for Victoria, nobody could stop anywhere else, for there, and there alone, were fortunes, and large fortunes, to be made. . . .

Never perhaps was there so large an immigration in so short a space of time into so small a place. Unlike California, where the distance from the Eastern States and Europe precluded the possibility of an immediate rush, the proximity of Victoria to San Francisco, on the contrary, afforded every facility, and converted the whole matter into a fifteen dollar trip. . . .

As to goods, the most exorbitant prices were asked and realized, for though the Company had a large assortment, their store in the Fort was literally besieged from morning to night; and when all were in such a hurry, it was not every one that cared to wait three or four hours, and sometimes half a day, for his turn to get in. The consequence was, that the five or six stores that were first established did as they pleased.

"

As well as the miners, the rush attracted many anxious entrepreneurs like Gibbs:

"An indescribable array of Polish Jews, Italian fishermen, French cooks, jobbers, speculators of every kind, land agents, auctioneers, hangers on at auctions, bummers, bankrupts, and brokers of every description. . . . To the above lists may be added a fair seasoning of gamblers, swindlers, thieves, drunkards, and jail birds, let loose by the Governor of California for the benefit of mankind, besides the halt, lame, blind, and mad. In short, the outscourings of a population containing, like that of California, the outscourings of the world.

"

Victoria stands on a small harbour in a beautiful setting. To the south, across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the sharp snowy peaks of the Olympic range rise dramatically into the sky. On clear days, one can look eastward to the immense cone of Mount Baker, a dormant volcano on the American mainland across the Salish Sea. The sea itself is dotted with green islands.

The city today is one of the loveliest and most comfortable in North America, but in the summer of 1858, Victoria must have been a singularly unpleasant place, despite the scenery and the praise of Wellington Moses. The old settlers’ small, whitewashed cottages were now surrounded by jerry-built shanties and hundreds of tents. The once-grassy streets were quagmires so deep that everyone—even ladies—wore high boots. And though the Pacific Northwest is notoriously rainy, water was scarce and expensive—a nickel a bucket.

The town was also crowded with Indigenous peoples, whose encampments ringed the settlement. Haida, Heiltsuk, Tsimshian and Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw travellers, among others, visited Victoria to trade, socialize, work or simply enjoy the excitement.

With the influx of thousands of gold seekers into the previously sedate town, the period was characterized by chaos and social upheaval, as well as the mixing of people from different backgrounds and cultures. To some White citizens, this disruption to the social order was deeply unsettling, as demonstrated by such accounts as that of Matthew Macfie, a Congregationalist minister who observed the sexual and romantic interactions between White men and Indigenous women with a combination of moral indignation and paternalism:

"The crowds of the more debased miners strewed in vicious concert with [Indigenous women] on the public highway presented a spectacle diabolical in the extreme . . . the extent to which the nefarious practices referred to are encouraged by crews of Her Majesty’s ships is a disgrace to the service they represent, and a scandal to the country. Hundreds of dissipated white men, moreover, live in open concubinage with these wretched creatures.

"

In all this uproar, Gibbs and the other Black immigrants worked frantically to settle themselves. Gibbs had not exaggerated the scope of land speculation. The government itself was legally forbidden to sell land in parcels smaller than twenty acres; town and suburban lots were sold by the HBC and private owners, who soon grew rich. As Waddington described it, “one half of a fifty dollar corner lot, the whole of which had been offered successively for 250, 500, 750, and 1000 dollars, and finally sold for 1100 dollars, was resold a fortnight afterwards, that is to say the half of it, for 5000 dollars. Old town lots, well situated, brought any price, and frontages of 20 and 50 feet, by 60 deep, rented from 250 to 400 dollars per month.”

Miners, real estate speculators and entrepreneurs were dealing with big money, and some did indeed get skinned.

Bothered and bewildered though he may have been, Gibbs landed on his feet. Customers snapped up his miners’ supplies at prices far higher than San Francisco’s, and he at once ordered more. For $3,000, he acquired a lot and house. He paid $100 down, with $1,400 to be paid in two weeks and the rest in six months.

“Previous to purchasing the property,” he wrote in his autobiography, “I had calculated the costs of alteration and estimated the income. In twenty days, after an expenditure of $200 for improvements, I found myself receiving a rental of $500 per month from the property, besides a store for the firm. . . . The trade my mother insisted I should learn enabled me to do this.”

With half the house providing rent, Gibbs used the other half as the premises of a firm whose ads were soon running in the Victoria Gazette:

"Lester & Gibbs

Dealers in Groceries, Provisions, Boots, Shoes, &c.,

Wholesale & Retail

L. & G. having permanently established themselves in Victoria, would respectfully call the attention of Families, Miners and the public generally to their very superior stock, to which they are receiving additions by every arrival.

N.B.—Consignments solicited, and attended to with promptness and dispatch.

"

The firm was the HBC’s first competitor in Victoria, and therefore among that happy group of businesses that, as Waddington put it, “did as they pleased.” Gibbs could soon buy a five-acre lot at Michigan and Menzies in the James Bay neighbourhood, build a house and hire a Haida manservant.

On his journey north, Gibbs had seen “an incessant social hilarity, a communion of feeling, an ardent anticipation that cannot be dormant, continually bubbling over.” That climate of opportunity clearly sustained itself in the colony.

“We received a warm welcome from the Governor and other officials of the colony,” Gibbs later wrote, “which was cheering. . . . British Columbia gave protection to both [life and property], and equality of political privileges. I cannot describe with what joy we hailed the opportunity to enjoy that liberty under the ‘British lion’ denied us beneath the pinions of the American Eagle.”

Other Black residents were taking advantage of that opportunity as well. Nathan Pointer, who had been Gibbs’s first partner in San Francisco, opened a large clothing store. Wellington Moses was soon running the Pioneer Shaving Salon and Bath Room (Private Entrance for Ladies). He and the other Black immigrants virtually monopolized barbering. Fortune Richard worked as a ship carpenter. Archy Lee, who had helped start the exodus, found work first as a porter and later as a drayman. A Virginian named Joshua Howard advertised himself as an “Attorney and Counsellor at Law . . . Advice in the law, to the poor gratis.”

Black entrepreneurs owned and ran some of Victoria’s new restaurants and saloons. According to James K. Nesbitt, the best restaurant in town was Ringo’s, on Yates Street. Nesbitt quotes a writer in the 1880s: “Every notable who came to Victoria in those days was escorted to Ringo’s for a square meal. This was considered the highest mark of hospitality.”

Samuel Ringo, a big, gentle man, had been a slave most of his life. After nursing the man who enslaved him through an attack of smallpox, Ringo had contracted the disease himself; when he recovered, his owner freed him.

Black and White customers alike patronized his restaurant, but for all its prestige they were often rowdy. On one occasion, a man left his shiny new plug hat on the counter while he enjoyed his meal. “When he came to replace his hat on his head, his horror may be imagined to find the juice of half a dozen eggs, and the oil from a pound of soft butter, trickling down his face.”

A year or two later, according to Nesbitt, two American customers—sympathizers with opposing sides in the US Civil War—got into an argument. “Blows were exchanged and pistols drawn. Ringo, in the kitchen, heard the row, and running out threw his great long arms about both men and gathered them to his greasy breast. He held them there as in a vise, until they consented to put up their pistols and shake hands.”

Within a very short time, Black people were working at every level of the colony’s economy, from manual labour to the professions. For a few weeks in June 1858, they even policed Victoria. Douglas himself seems to have appointed them, perhaps as a way of reminding the Americans that they were on British soil: most were Jamaicans, and all were British subjects. (It’s unclear whether such persons had come from California or directly from British possessions in the Caribbean region.) A letter from a prospector, written in October 1858 and uncovered by gold rush historian Chris Herbert, vividly conveys White American hostility to the constables in particular and the British in general:

"I will write you a few lines and tell you how I am and what my Prospects are if you got my last letter dated in Sept last at sea on my Passage to this country you know how I have been and what I have been doing up to that time so I want tell you that over again.

Well after I got the Machinery put up in the Boat she commenced running and has been running ever since and I expect she will run until the River freezes up that will be about 2 months and then I shall return to California I am already heart sick and tired of this country and the English Laws I think the English are as general thing the meanest People in the world When the Americans came here the first thing they done was to appoint Negro Police over them but the Americans swore thay would kill every one of them and that they would do as thay had a mind to if thay did not put other men on the Police & at that time there was Negroes and put English in there Place but thay impose thair stringent laws and taxes and all other impositions on the American People as far as thay can the People are scatered around the country now and thay have a better chance it don’t make so much difference to me as I am on the steamer all the time and make it my Home on her but to se the airs the English Put on over the American it is Enough to make any one sick talking about their country and the gold that is in it thay thing there is not another place in the world like it . . .

"

Despite their impressive uniforms—blue coats, red sashes and high hats—the new constables met immediate resistance from the Americans. In one incident, a thief caught red-handed in a miner’s tent admitted his guilt but refused to be taken to jail by a Black constable. Enough of his fellow White men backed him up to make an arrest impossible. After several such incidents, most of the Black policemen were withdrawn from service. One, Loren Lewis, stayed on for several years as constable for the Songhees Reserve outside Victoria.

The social backgrounds of the Black Victorians were varied. Some, like Archy Lee, were Southern-born ex-slaves. Others, like Gibbs, were freeborn Northerners who regarded themselves as self-starting Yankees. Some were well educated: John Craven Jones and his brothers William and Elias were graduates of Oberlin College in Ohio, and Fielding Smithea had also attended Oberlin. Many, including Gibbs, were self-educated. Others were illiterate or nearly so. While most had been born in the US, a sizable minority were British subjects born in the West Indies or in Britain itself.

The Black American expatriates were ready to commit to their new home. An 1858 report in the Victoria Gazette listed recent applicants for British citizenship. The complete list, all but one of them Black men, is worth reproducing as a cross-section of the pioneers’ occupational diversity:

George Henry Anderson, farmer

William Isaacs, farmer

Fielding Spotts, cooper

James Samson, teamster

Richard Stokes, carrier

John Thomas Dunlop, carman

Nathan Pointer, merchant

Augustus Christopher, porter

Isaac Gohiggin, teamster

William Alexander Scott, barber

Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, merchant

William Miller, saloon-keeper

George H. Matthews, merchant

Robert Abernathy, baker

Henry Perpero, gardener

Thomas Palmer Freeman, storekeeper

Stephen Anderson, miner

Edward A. Booth, water-carrier

William Grant, teamster

Henry Holly Brenen, cook

Samuel John Booth, caulker

Joshua B. Handy, restaurant-keeper

William Brown, merchant

Timothy Roberts, teamster

Matthew Frederick Monet, fruiterer

John Baldwin, greengrocer

Stephen Whitley, laundryman

Charles H. Thorp, ship carpenter

George Washington Hobbs, teamster

Willis Carroll Bond, contractor

Elison Dowdy, painter

Archer Fox, barber

Robert H. Williamson, blacksmith

Randel Caesar, barber

Fortune Richard, ship carpenter

T. Devine Mathews, carrier

Robert Tilghman, barber

Charles Humphrey Scott, grocer

Thomas H. Jackson, drayman

Ashbury Buhler, tailor

Archer Lee, porter

John Lewis, porter

Thorenton Washington, carpenter

Lewis Scott, carpenter

William Glasco, teamster

John Dandridge, no occupation

Adolphus C. Richards, plasterer

Fielding Smithers [sic—should be Smithea], messenger

John E. Edwards, hair dresser

Paris Carter, grocer

Augustus Travers, porter

Richard Jackson, gardener

Patrick Jerome Addison, farmer

Only a few of these original applicants reappear in later censuses of Victoria and Vancouver Island; while a few may have resettled on the mainland or elsewhere in Canada, most, evidently, would return to the US after the Civil War.

Diverse though they were in their origins and abilities, the Black pioneers were, in general, tough, resourceful, self-starting and ambitious. Migration from the eastern US to California was hard even for people with money and privilege. For Black trailblazers, the journey had been even harder. To succeed in a White-ruled frontier state had demanded brains, talent and courage. By a rigorous self-selection process, therefore, only the best-adapted Black arrivals reached the goldfields.

The White society in which the Black immigrants found themselves was undergoing rapid change. F.E. Walden, a historian of British Columbia’s early days, has outlined its basic structure:

"The British governing clique held firmly to its position as the upper class in Victoria. Governor Douglas and the succeeding governors, their wives and families, entertained the high supporting officials of the colony, most of whom were resident in Victoria. High-ranking officers of the Royal Navy and the Royal Engineers were included in this circle, and junior officers of the Services provided suitable escorts for the young ladies of these families. High officials of the Hudson’s Bay Company completed this ruling hierarchy. Only slightly below ranked the professional section of the population, consisting almost entirely of British doctors, lawyers and clergy.

The bulk of the population formed what might be properly called a “healthy middle class,” or proprietary group, led by American and Jewish merchants. With various German, Negro and British shop-keepers, this group took an active and growing part in municipal affairs, political, economic and social. Supporting this middle class were the skilled tradesmen of nearly every nationality, although as a group they did not make their influence felt to any great extent.

Caste division as it applied to the labouring population transcended the bounds of nationalities, and the opportunity to advance into the ranks of the merchant section grew. German, Italian, Negro, Indian, Chinese and Kanaka household servants formed the large proportion of this group of semi-skilled and unskilled labour at the bottom of the social scale.

"

A contemporary observer, Rev. Matthew Macfie, saw Victoria’s society somewhat differently: “The Government officials,” he wrote in 1865,

"constitute the centre of the social system (still in a formative state), and around it multitudes of broken-down gentlemen and certain needy tradespeople rotate. The most wealthy members of the community have, in general, more money than culture—a condition of things always incident to the early stage of colonial development. Many of them owe their improved circumstances simply to being the lucky possessors of real estate at a time when it could be bought for a nominal amount. Some who eight years ago were journeymen smiths, carpenters, butchers, bakers, public-house keepers, or proprietors of small curiosity shops in San Francisco or Victoria, are now in the receipt of thousands of pounds a year.

"

The British-born Macfie saw a lack of a firm class structure in the new colony:

"The immigrant accustomed to the distinctions of class obtaining in settled populations will be struck to observe how completely the social pyramid is inverted in the colonies. Many persons of high birth and education, but of reduced means, are compelled, for a time after their arrival, to struggle with hardship, while the vulgar, who have but recently acquired wealth, are arrayed in soft clothing and fare sumptuously. Sons of admirals and daughters of clergymen are sometimes found in abject circumstances, while men only versed in the art of wielding the butcher’s knife, the drayman’s whip, and the blacksmith’s hammer, or women of low degree, have made fortunes.

"

Macfie cited the case of a gentleman charged with being drunk and disorderly; the arresting constable was his own former manservant. Macfie also took amused note of the number of apparent fugitives from justice: “Druggists inform me that the demand for hair-dye by immigrants is so large as to be quite noticeable. The cause of this expedient, in such a country, may be readily conjectured.”

Amid all this boom-town upheaval, most of the British-born elite found the Black community an island of stability. Rev. William F. Clarke, a Congregational minister, said of them that “a large proportion . . . are very respectable and intelligent; indeed as a whole they are superior to any body of coloured people with whom it has been my lot to meet.”

A more patronizing tone, however, is evident in a description of the Black community by Lt. R.C. Mayne of the Royal Navy, who was stationed at Esquimalt Harbour near Victoria during the gold rush: “As a rule these free negroes are a very quiet people, a little given perhaps to over familiarity when any opening for it is afforded, very fond of dignity, always styling each other Mr., and addicted to an imposing costume, in the way of black coats, gold studs and watch-chains, &c.; but they are a far more steady, sober and thrifty set than the whites by whom they are so despised.”

These writers express an odd sort of tolerance born of social snobbery. As upper- and middle-class Britons, they discriminated by class, not colour. A solid merchant like Mifflin Gibbs or Peter Lester therefore merited more respect than a labourer of any race.

Another reason for the British colonists’ fairness toward the Black community was that, outnumbered by the White Americans who now formed the great majority of Victoria’s inhabitants, the British elite soon found that such expressions of tolerance helped set them apart from the White Americans they saw as uncouth, hypocritical, vulgar upstarts. Douglas himself seems to have taken a certain quiet pleasure in needling the Americans, and not only on the race issue. Just before the gold rush, for example, he had blandly declined to return two US Army deserters to Washington Territory.

Some of the Black immigrants, of course, were as tough and brutal as some of their White neighbours. One Black teamster, trying to get a wagon through the muddy streets, lost his temper and beat his horse to death. Other Black individuals were notorious brawlers and thieves, and one or two were suspected of murder. A Black man named Thomas Brown was murdered in 1860 by a Tsimshian man named Allache because Brown had sexually assaulted Allache’s wife. (Allache, not yet twenty, was hanged.) Some sold whisky and were regular patrons of the brothels on Cormorant Street. Yet in proportion to their total numbers, the Black people who broke the law were a very small group. On balance, James Douglas could scarcely have made a better choice of settlers.

Despite the government’s support for them, the Black community soon felt the need to put their case to the public. In February 1859, Rev. J.J. Moore—one of the San Francisco clergymen who had supported the emigration—published a letter in the Colonist to explain the motives of the Black settlers. After cautioning his readers not to expect the Black immigrants to act as a unit, Moore outlined the problems they had faced in California. Then he went on to say:

"From this prejudice we have fled to a country governed by a nation far-famed for justice and humanity. Hasty fortunes we seek not; with some of us losses have been sustained, that the chief advantages of the country cannot briefly indemnify; but this is a secondary consideration with us: the full, free, and peaceable enjoyment of those highest inherent rights with which Heaven has gifted man, is the crowning thought with us, not dollars and cents. . . . We come here not to seek social favors, but to enjoy those common social rights that civilized, enlightened, and well regulated communities guarantee to all their members. We come not to seek any particular associations—(those of us who understand ourselves;) we only desire social rights in common with other men. . . . We have come to this country to make it the land of our adoption for ourselves and our children. We have come to possess the soil; to till the earth; to reap its productions, extract its minerals; to mould its rocks and forests into firesides; and to fill the solitary places with joy and gladness; . . . and build up for ourselves and our children happy hopes in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

"

Other groups were establishing themselves at the same time. One sea captain remarked that Victoria’s population was racially more diverse than that of any port he had ever seen. Hawaiians (usually known as “Kanakas”) arrived in considerable numbers; so did Chinese, Indian, Chilean, Mexican and European immigrants of all nationalities who mingled in Victoria’s streets and encampments.

But White Americans predominated and showed their attitude to other races in sometimes brutal ways: one Chinese immigrant, passing by some White miners on his way to get water, was shot five times without provocation.

In Victoria’s fluid society, the Black arrivals soon struck roots and began to flourish. Many of their fellow immigrants were transients, unable to contribute much to the colony. The Black settlers, however, became “the ‘old families’ and monied aristocracy,” as Macfie called them.

Yet it was precisely their social virtues that led them into repeated conflicts with the White society around them. The first of these conflicts was religious, and Reverend Macfie was in the thick of it.