Chapter Sixteen

Victory, but at What Cost?

For Britain and France, it was a victory that was all but indistinguishable from defeat. Just being able to endure it was seen as heroic.

—Geoff Dyer

When World War I was over, the men and women who took part could be forgiven for wondering whether it was all worth it. Even after the Armistice, many languished overseas, waiting for demobilization and transport home. There were riots in England as Canadian soldiers sat out another winter in cold barracks with bad food. This was not a new world fit for heroes, but was more of the same.

Teetering governments hoping to prop up their support gave women the vote, but money was tight and genuine reform was in short supply. The “temporary” income tax introduced during the war never went away.

Many of those who returned to British Columbia just wanted to return to their old jobs and home life. But as BC historian Margaret Ormsby wrote, “Most of the large companies, burdened with stockpiles of manufactured goods, were firing rather than hiring. The worst conditions prevailed in Vancouver. In the mining camps of the Interior, there were almost no jobs.”

Who was to blame? In this anniversary year, the historians can’t even agree on who started the war or why it happened. Canada’s Margaret MacMillan concludes that those who took us into the war could fairly be accused of a “failure of imagination in not seeing how destructive such a conflict would be.”

The mud of the Western Front, the punishing artillery, the poisonous gas, the machine guns and flame throwers, the bombing from above and the explosions from tunnels below, the prospect of being blown to bits for the sake of a muddy stretch of trench that could be lost tomorrow—all these horrors left an indelible mark on a generation and their offspring.

Contents

Influenza

Soldier Settlements

The Prince of Wales Visits

General Currie’s Image Problem

A Journey Back in Time

Making It Relevant

Article: A City Goes to War: Victoria’s War Story on the Web

Cycling into History

Article: Marking Sacrifice: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Brigadier General Henry Thoresby Hughes, Royal Canadian Engineers and Monument Builder

Journeys with My Father from Menin Gate to Vimy

Paying Respects

Our Journey into the Great War

Terms of Engagement

My Search for Albert Ernest Rennie

He Never Made It to Europe

Sidebar: A Message from the Canadian Letters and Images Project

Sidebar: From Our Listeners

Influenza

The postwar influenza outbreak killed more than fifty million people worldwide. Fifty thousand Canadians died, with over four thousand in BC. One thousand were First Nations, a stunning reminder of the smallpox epidemic that wiped out tens of thousands of Native people in BC just decades earlier.

The so-called Spanish flu was universal in its reach, spreading around the globe, stretching medical resources already stretched thin by four years of war and visiting upon the civilian population another shocking death toll just as the nightmare seemed to be ending.

Mark Humphries, a history professor at Memorial University in Newfoundland, believes the influenza epidemic may have a British Columbia connection. Humphries has written that the flu most likely emerged in China in the winter of 1917–18, “diffusing across the world as previously isolated populations came into contact with one another on the battlefields of Europe.”

How did it spread? Humphries believes it can be traced to the Chinese Labour Corps, the men recruited by the British government in Asia, transported to British Columbia by ship and then sent by rail across Canada to supply much-needed labour on the Western Front. Some of those men were already sick with a mysterious illness before they left home. While some quarantine efforts were made, they were insufficient. The Spanish flu probably had nothing to do with Spain.

Soldier Settlements

After the optimistic years under Premier Richard McBride, the new premier, John Oliver, ushered in a long period of sobriety, politically and practically. Alcohol was prohibited for about four years, from 1917 to 1921, and the political climate was pretty tame too. Oliver was a prosperous farmer, and he assumed the farming life was just the thing for returning soldiers. “He had taken it for granted, without either enquiry or consultation, that the soldiers would prefer to settle on the land,” wrote Margaret Ormsby.

The Oliver government quickly moved ahead with plans to reclaim the wetlands of the Sumas Prairie in the Fraser Valley, to irrigate the desert in the south Okanagan and to establish soldier settlements at Merville on Vancouver Island, at Creston in the Kootenays and at Telkwa in the north.

But as the song goes, how are you going to keep them down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree? “When only a few of the soldiers took advantage of his offer of low-priced land, [Oliver] felt the rebuff keenly,” said Ormsby. “He had dreamed of providing a farm for every hero.”

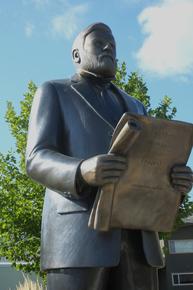

The town of Oliver in the South Okanagan is named after “Honest John” Oliver. There’s a statue of him in front of the old municipal hall. Today, the town is the centre of the Okanagan fruit and wine industry. But it wasn’t really built up by returning soldiers. “When it was realized that only a small portion of the land would be taken up by returning veterans the government decided to give everyone a chance to buy land,” wrote Julie Cancela in her book about the irrigation project called The Ditch.

The move to broaden the market for orchards came after considerable government investment to build a network of concrete ditches, siphons and flumes. Bringing water to the desert and laying out the orchards was expensive, probably close to five million dollars. But the good news was that it put local men to work at a decent wage. Men made about five dollars a day and the project took until 1927 to complete. It employed hundreds and made it possible for some of those men to be the first to buy parcels of land.

The soldier settlement of Merville on Vancouver Island with its stump farms was probably less successful. The returning soldiers named the community for a French village where they fought. Writer Jack Hodgins grew up there and wrote about it in his book Broken Ground. The land wasn’t much friendlier for farming than the war-torn landscape they had left behind. There were huge trees and stumps to be cleared—often using explosives, which must have been a shock to men already terrorized by the sound of artillery.

“For those returned Soldiers who were ‘rewarded’ with land for farming, clearing the stumps must have seemed like a continuation of war,” Hodgins says. “Some were wounded by

explosives. And of course many more were wounded or killed in the logging camps. Most of them ended up in the logging camps because it became clear that very few of them would ever make a living off their farms. The land was suitable only for timber.”

The Prince of Wales Visits

When the Prince of Wales visited British Columbia in 1919 to pay tribute to the province’s veterans, one of the places he went was Merville. A Pathé newsreel from the visit shows the stumps and the explosions. It looks like a battleground.

The Prince toured all over the province, meeting servicemen in the cities, visiting veteran convalescent homes on the coast and in the interior, travelling by steamboat up the Okanagan and through the Kootenays. Men from all over Canada took their discharge in British Columbia. Many ended up in veterans’ hospitals in BC and struggled for years with their injuries, and the complications from gas and shrapnel. But the royal tour was a triumph of public relations, providing the public with a glimpse of a glamorous royal who would be caught up in a scandalous abdication crisis on the eve of another world war.

General Currie’s Image Problem

For Victoria’s Arthur Currie, Armistice ended the fighting but did not end his personal struggles. For years afterwards, he was in court defending his reputation and his decision to sacrifice Canadian lives in the last months of the war. Also haunting Currie was a very poor decision he made before the war to salvage his failing real estate business. While he may have been a dedicated commander, he was a reckless businessman, and to get out of a tight spot when the Victoria real estate market collapsed in 1913, he “borrowed” over ten thousand dollars in regimental money—and used it to pay off some debts.

To compound his problems, the embezzlement was not a secret in political circles. Prime Minister Borden and some of his key ministers knew about it, and while they admired Currie’s leadership abilities, they were very concerned that if the fraud became public knowledge, Currie would be ruined and they would be looking for a new commander for the Canadian Corps. Some of Currie’s enemies also knew of it, most prominently Minister of Militia and Defence Sam Hughes, who started the war as a personal friend and supporter, but turned on Currie as the general rose and Hughes fell.

Currie was strangely negligent in correcting the impropriety even when his own pay packet improved as he rose through the ranks and had an opportunity to pay the money back. “It is difficult to reconcile Currie’s reckless personal behavior in relation to this impropriety with that of the public general who approached war in a methodical, careful, and informed manner,” wrote Tim Cook in his biography.

The whole episode is a blot on the Currie reputation and suggests a personal sense of entitlement, a belief that his personal sacrifices in leading the Canadian Corps provided some exemption from scrutiny of his finances. Mercifully, at one point during the war, two of Currie’s subordinate officers who were successful businessmen stepped in and lent him the money to pay back the debt. Victor Odlum and David Watson rescued Currie from scandal but also put him a tight spot because he must have known that if he moved to demote either man, they could reveal his secret.

Sam Hughes made Currie but came to hate him. Why didn’t Hughes expose the fraud? He was certainly prepared to destroy the Currie reputation in other ways at the closing of the war. Hughes became convinced that Currie had recklessly sacrificed Canadian soldiers in the final one hundred days. Hughes’s mind was also poisoned by envy. It was understandable. Hughes had been removed from office at the height of his powers. Once he was the admired strongman of the Canadian government’s war effort, but Prime Minister Borden came to distrust Hughes’s eccentric and erratic ways and demoted him. He spent the remaining years as a humble backbencher, powerless beyond the occasionally stinging criticisms he was able to deliver in Parliament. At the same time, his nemesis Currie had gone from strength to strength so that by the end of the war he was one of the most respected generals on the Western Front.

Hughes was ill by this time and died in 1921. But before his death, he kept up a steady barrage of criticism, laying the blame for the high death toll in the final months of the war on Currie’s doorstep. “I created General Arthur Currie,” he told the House of Commons, but as a creator he was not happy with the result. “I have no hesitation in saying that many Canadians would be above the sod today if he had not carried out his tactics and strategy in relation to [the Battle of] Cambrai.”

Hughes could keep up the accusations unchallenged because he also knew the more devastating story of Currie’s embezzlement. So Currie remained silent as the stinging criticisms spread in the media. There was little he could do. And when Hughes was dead, the rumours continued to fly. It was not until 1927, when a newspaper editorial appeared in the Port Hope Evening Guide, that he finally decided enough was enough. The newspaper wrote:

It was the last day; the last hour, and almost the last minute [of the war], when to glorify the Canadian Headquarter staff, the Commander-in-Chief [Currie] conceived the mad idea that it would be a fine thing to say that the Canadians fired the last shot…But the penalty that was paid in useless waste of human life was appalling.

Currie decided to sue for fifty thousand dollars. The trial dragged on through 1928 and rehashed much of the rumour and innuendo. In the end it was a win for Currie but a hollow one. A jury found the newspaper guilty of libel but awarded Currie only five hundred dollars in damages. The war, the trial and the public humiliation shortened Currie’s life considerably. He died in November 1933, just a few weeks after Armistice Day. He was only fifty-seven years old.

The pretty little cottage that the Currie family lived in is still standing in Victoria. It has been restored to its former glory and there is talk of erecting a statue in his honor. But most British Columbians have forgotten that this struggling real estate agent was Canada’s greatest battlefield general.

A Journey Back in Time

Our listeners and contributors have been united in their desire to keep the story of the Great War fresh in the minds of the next generation. Teachers like Dianne Rabel in Prince Rupert and Gina McMurchy-Barber here on the south coast have made it a central part of their curriculum. Here’s Gina’s story and more from people who have reconnected with the past in moving ways.

Making It Relevant

By Gina McMurchy-Barber, Surrey

Early in my career I wanted to teach my students about Canada’s participation in the Great War and World War II. I grew up with a healthy respect for these periods in world history because my dad served for five years in World War II. But how to make a bunch of eleven-year-olds care when the war was so long ago, so far away and had nothing to do with their lives of Nintendo, cartoons and virtual pets was another matter.

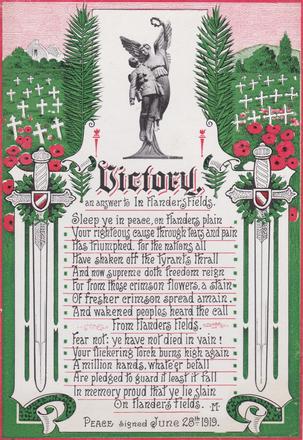

Many of my students had been reciting “In Flanders Fields” since kindergarten, wore poppies and stood for two minutes of silence on cue at our school assemblies. But one year I hoped to achieve more—for them to be really moved by these events and to leave them with a deeper awareness and appreciation. It occurred to me the only way this could happen was to find a way to make it relevant to them. So we began to find the connections in their own family history by interviewing relatives or reading family accounts.

As we progressed toward Remembrance Day, students began to light up as places and names became more familiar in our history lessons. “My great grandfather fought in the Somme,” one piped up. “My uncle collects stuff from the wars and showed me a rifle with a bayonet,” another was keen to tell. One boy learned that while his Chinese great-grandfather was fighting the Japanese, his British great-grandfather was on the other side of the world fighting the Germans.

I could see the class was beginning to get it. But the best was still to come—it was to bring history to life by getting them to take parts in a play I wrote called True Patriot Love. As the students learned their lines they inadvertently memorized history, sang songs from the era like “Pack Up Your Troubles” and “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” acted out real people’s experiences and came to some important conclusions—war was not glorious, but the people who fought and died were.

Ever since that year I have taught in different schools and different ages, but have always found that with a little effort students learn to care about the Great War when they find how it connects to them. It’s harder now with many of those with direct experiences gone, but all the more reason to put our family stories in writing. A few years ago I was at a teacher conference. At break time I was making my way through a crowd when I felt a touch on my arm. When I turned I was face to face with one of the students who had been in my class that first year I taught about the wars. She was a brand new teacher, attending her first conference. “I still remember the history lessons,” she said. “What we learned from that play—it was called True Patriot Love…right?”

Young people can appreciate the sacrifices made by those who fought and died if they learn to see that World War I and other wars were events that touched everyone’s life, including their own. That’s when they can truly say, “We will never forget.”

Gina McMurchy-Barber is the recipient of the Governor General’s Award for Excellence in Teaching Canadian History.

[Click here for A City Goes to War: Victoria’s War Story on the Web]

Cycling into History

By Barry Bogart

Almost a hundred years after Vimy. Have we learned anything? I have completed my fourth bicycle tour in Europe. My brother has a place in the north of France near Calais—Montreuilsur-Mer, home of Victor Hugo and locale for Les Mis. On the previous three tours I had cycled around that part of France for many, many kilometres. I never made any attempt to understand the history of the area, but I kept randomly coming across large and small gravesites.

Last spring I watched on TV a ceremony rededicating the Vimy Memorial, and it really moved me. That led me into months of research into the “War to End All Wars.” It turned out that much of the action took place literally under my feet where I had cycled up through Flanders into Belgium. I took a combination of trains and bikes, which worked out very well. I went by train to Bruge, then took the LF1 Noordzeeroute south from Bruge through Nieuwpoort to Diksmuide. This part of the LF1 and a little farther on pretty well follows the front lines in World War I. But you don’t realize it until you see the vast monument and cemetery in Diksmuide.

After Diksmuide I switched to the LF6 route, which follows a circle around Ypres through Poperinge. I camped near there and then doubled back through Ypres to visit the many memorials of Passchendaele. It was around there that I saw the first really big cemeteries— English, Canadian, French. Over eighty thousand buried in each. But I first saw a little one— Essex Farm—where John McCrae wrote “In Flanders Fields” just before he died (and yes, there are poppies by the roadside all around there). This was one of the more moving I saw as I walked by the Canadians who died there, their headstones decorated by students from “Regina Catholic Schools.”

Along the road to Lens and on to Vimy were scores more cemeteries for the French, German and Commonwealth troops. By then I was used to it, but Vimy was still to come. I had a good climb up to Vimy Ridge, and you can see the memorial from there. Just before you arrive, there is a Café Canadien at the top where I stopped to have a café au lait (no Molson there, nor a Tim’s, but I was about to be on Canadian soil).

The land around Vimy Ridge has been left scarred as it was then, by bombardments. But now sheep peacefully graze on it. There are warning signs about not walking off the paths due to the unexploded ordnance still there. (I wondered if the sheep ever found any.) The memorial itself is majestic, but mournful beyond description, rivalled only perhaps by the Brooding Soldier statue I saw the day before. I spent quite a lot of time there and at the nearby Canadian cemeteries. British Columbians were well represented there, sadly.

[Click here for Marking Sacrifice: Commonwealth War Graves Commission]

Brigadier General Henry Thoresby Hughes, Royal Canadian Engineers and Monument Builder

By Sara Carr-Harris, Victoria

Brigadier General Henry Thoresby Hughes, my grandfather, came to Canada from England in the late 1800s and worked for the CPR. He is, as far as I know, the only person to have obtained his engineering degree, by correspondence—and by lamplight at that—while working for the railway. He knew Van Horne, and he designed bridges and buildings for the CPR, the stations that had the French look about them.

About 1904, the Royal Canadian Engineers was formed and he then joined up, having married my grandmother, from Montreal. Then he was stationed in charge at Work Point Barracks, Esquimalt, in about 1907 or 1908. My grandmother was with him along with their two sons, my father and his brother, who got into mischief at the army camp. Grandfather shut them up in the jail after they lit a fire to welcome mother home from a trip on one of the big CPR ships that used to come into Victoria Harbour. I believe the fire must have got out of control because the story was that the men were having to run in their white summer drill to get the fire out!

Brigadier General Henry Thoresby Hughes had a distinguished career with the Canadian military (CMG, DSO, received from King George V, Buckingham Palace), was mentioned in dispatches and after the war was chief engineer in charge of construction of Vimy and our other Canadian World War I memorials at Bourlon Wood, Le Quesnel, Dury and Courcelette in France and St. Julien, Hill 62 (Sanctuary Wood) and Passchendaele in Belgium.

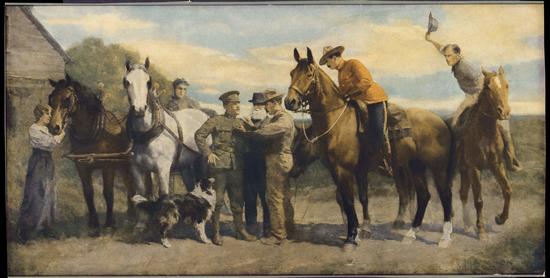

He retired to Elk Lake, Victoria, in the 1930s and died in 1947. When my father lived at Elk Lake in the 1920s, my grandfather sent him his warhorse, Bill. He was an amazing jumper and I often wondered where he came from, probably from a stable in England. However, he was full of shrapnel from the war and went lame. Bill had to be put down, much to my father’s dismay as Bill was a very special horse and, I believe, the only warhorse sent to Western Canada from France.

Journeys with My Father from Menin Gate to Vimy

By Lesley Patten Elarid and her mother, Jacqueline Patten

We can truly say that the whole circuit of the Earth is girdled with the graves of our dead. In the course of my pilgrimage, I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon Earth through the years to come, than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war.

—King George V, May 11, 1922

History has always been a topic of discussion at our home, and my dad, Jack Patten, was avidly interested. From his experience as a boy during World War II in England, to his time in the Canadian Scottish Regiment on Vancouver Island, he was always reading, talking with veterans and travelling to the battlefields of Europe.

The first of nearly forty tours my father organized to Europe began in 1990. I was just sixteen at the time, taking time off school to take a bus tour with twenty-seven World War II veterans and their wives to World War battle sites. How can you beat hearing first-hand stories of the war from those who were there? Over the years, my father built strong friendships with local teachers, mayors of villages and interested local citizens in France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Everywhere we went, we were welcomed with open arms, for all that the Canadians before us had done. It seems they truly follow the act of remembrance.

Each cemetery, battlefield or local village was a memorable experience. One very moving ceremony was in Démuin, France, which has forty-two graves, most of them 16th Battalion Canadian Scottish members from Vancouver Island. A wreath was laid at Piper Paul MM’s grave and some French pipers played the lament, in the company of veterans and the bulk of the small village. Everyone retired to the mairie (city hall) for a vin d’honneur at the village of Aubercourt, the final objective of the battalion on that day.

From that first trip with veterans who learned about the World War I experience, to current serving soldiers, past Lieutenant-Governors of BC and interested travellers who have accompanied us on the trips, all have been so moved by the contributions of Canadians during the wars and the well-preserved Commonwealth war graves and monuments, as well as by the local people. To stand in small fields that were once battle zones, to see the amazing signs of remembrance, all Canadians should have this experience. Some notable World War I locations include:

- The Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing is a war memorial in Ypres, Belgium, dedicated to the British and Commonwealth soldiers who were killed in the Ypres Salient of World War I and whose graves are unknown. There are over fifty thousand names listed. Each evening at eight p.m. the last post is played, a tradition that has continued since Armistice except during World War II.

- Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission burial ground that contains another thirty thousand names of soldiers whose graves are unknown. The local school children visit annually to host a picnic, so those lost can hear the sound of children’s laughter and know that their sacrifice was not in vain.

- The Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France is dedicated to the memory of Canadian Expeditionary Force members killed during World War I. It also serves as the place of commemoration for World War I Canadian soldiers killed or presumed dead in France who have no known grave. The remaining trenches in the area are available for tours.

There are tours available in the region and plenty of resources for those interested in World War I, such as the Western Front Association that educates the public in the history of the Great War. It is touching and awe-inspiring to be in the area that was the scene of so much death and destruction, and yet so necessary to visit to grasp the monumental effort that took place there so many years ago.

Paying Respects

By Ray Travers, Victoria

My son Michael Travers and I have comprehensive family history records on both my wife’s and my side of our family. This research made my trip possible. I have visited the World War I battlefields where Canada served many times. The most recent trip was in November 2011 when I visited sixteen graves of close family members—with descendants of common ancestors up to five generations back. Some family members who died were Canadians and others were British. Most died from 1916 to 1918.

In November 2011, I arranged a personal local guide for my tour. Over three days from Ypres in Flanders to Albert in the Somme, I visited all sixteen graves of my extended family. On each grave I left a small wooden cross with a poppy and took a photo. Some soldiers have no grave and their names are mentioned on the Menin Gate and the Vimy Memorial.

One of the graves I visited was my mother’s father (my maternal grandfather), who was an Englishman: Private Reuben Wagner (November 28, 1891–August 2, 1917), buried at Poelcapelle British Cemetery, West Flanders, Belgium. Another of the graves I visited was my dad’s father (my paternal grandfather), who was a Canadian: Captain and Quartermaster Oliver Travers, MC (April 1, 1876–October 29, 1917), buried at Brandhoek New Military Cemetery, West Flanders, Belgium.

Recent family history research suggests there are another three graves of my extended family who died on the battlefields of World War I. My family is probably not unique in our losses.

On this trip, I learned there are about a thousand Commonwealth War Graves Cemeteries in Belgium and France. About one half are small and seldom visited. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, in the tradition of an English country garden, will immaculately maintain all these cemeteries, forever.

This trip gave me a direct sense of the huge human impact of World War I on Canadians, the hard lessons learned as Canada became a nation on the battlefields—our Canadian soldiers, from Vimy forward, did not lose another battle in World War I. I also have some understanding how the hard lessons learned by our soldiers and nurses who returned from World War I helped create the Canada we know today.

Our Journey into the Great War

For the past two years, we’ve lived in the past, and travelled to battlefields in Europe and cenotaphs here at home. We’ve spent time in museums, met with the descendants of veterans and treasured the stories they shared with us online. We’ve come to know our own family stories better and we hope others have too. Th is book is our tribute to all those touched by the war years.

Terms of Engagement

By Mark Rennie Forsythe

This Great War project has propelled me on a fascinating personal journey, and judging from CBC listeners’ contributions, this has also been true for many others. Some family stories in these pages are finely detailed and intricately documented; others are like frayed strands to be tugged at a hundred years later. As you’ll read below, I’ve come to learn about my great-uncle Albert Rennie, someone I knew nothing about while growing up. I’ve also recently learned that Albert’s older brother, Robert Charles Rennie, also served. He survived the war but died before his time in 1934.

There have been surprises. Our chapter about BC’s Victoria Cross winners includes Robert Hill Hanna, from County Down in Ireland. He moved to BC in about 1904, worked in logging camps and signed up with Vancouver’s 29th Battalion—Tobin’s Tigers. Hanna would later receive the VC for bravery at the battle for Hill 70 in France, the same fight that cost my great-uncle Albert Rennie his life. On closer inspection, Robert Hanna came from Kilkeel, Ireland, the same coastal town my Forsythe ancestors emigrated from. A search of my family tree finds him connected through marriage, and to top it off, Robert Hill Hanna lived at Mount Lehman, just a short drive from where I now live in the Fraser Valley.

My grandfather Albert Forsythe enlisted with the 122nd Battalion near his home in Severn Bridge, Ontario. The nineteen-year-old “lumberman” worked at the local sawmill and was probably well suited for the “Muskoka Cracker Jacks,” as the 122nd dubbed themselves. They were off to Europe to fight the Kaiser as they sang, to “Crack the logjam.” They would later become part of the Canadian Forestry Corps, cutting timber for tunnels, dugouts, railways, duck walks for muddy trenches and plank roads. Twenty thousand Canadian soldiers were involved in this part of the war effort.

I did not hear my grandfather utter a word about his experiences; he died when I was a young boy, so I never got to ask him the questions that appear so obvious now. Albert’s eldest son, Hugh, later served during World War II and while stationed in England met his future bride, my aunt Doreen. This World War I project has helped me reconnect with her and my Forsythe cousins. A most wonderful gift.

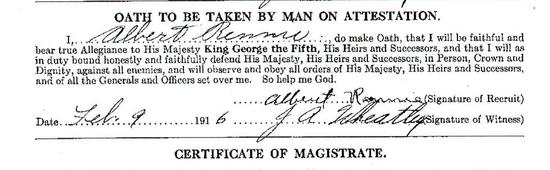

My Search for Albert Ernest Rennie

Height…5 ft 8 1/2 in.

Girth when fully expanded…37 ½ in.

Complexion…Ruddy

Eyes…Brown

Hair…Brown

Do you understand the nature and terms of your engagement?...Yes.

My middle name is Rennie, attached in tribute to my paternal grandmother, Helen (Rennie) Forsythe. As a very young child I remember cigarette smoke curling above her head like a halo, and a love that flowed like a deep, underground spring. I did wonder why my middle name wasn’t a more typical James, Michael or John. Rennie was formal. Adult. My parents’ marriage ended when I was four years old and my grandmother Helen died when I was nine, so links with my father’s family became more tenuous.

We did visit our father and his new family, and Aunt Dora and Uncle Joe’s near Orillia. Dora was my grandmother’s sister and also a Rennie; she and Joe lived about a two-minute walk away from a decommissioned hydro plant that harnessed the Severn River at Wasdell Falls. Aunt Dora was a champion baker who ruled her kitchen with generous panache; even the dog Daisie benefitted, treated to chicken livers cooked on the stove top. Uncle Joe was a gentle soul with an easy chuckle who rolled his own cigarettes and built their sturdy white house perched atop a jutting slab of granite. He was also responsible for the old hydro plant, which to an eight-year-old was like visiting Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory with its huge green turbines, ringed ceramic insulators and big copper switches.

Water spilled through gates inside the power house where we shuffled slowly across a narrow metal ramp above water crashing below. It was frightening—and thrilling. The roiling water made the building shudder and the sound reverberated up concrete walls to a high ceiling. I remember hearing fragments of a story about a drowned body, trapped against the dam’s workings. The river seemed a malevolent force, but we swam and fished in the tame waters below the dam.

By the time I was nineteen, both Uncle Joe and Aunt Dora had died, and I had moved to British Columbia. My relationship with my father was paper-thin; we spoke with each on the phone—awkwardly—about once a year. I knew very little of his family history, especially the part that contained my middle name, which was also his middle name. Some years later I returned to Ontario with my own young family and visited the family graveyard. My aunt, uncle and father are buried in a plot beside Dora’s parents, George and Isabel Rennie, and I was surprised to see another Rennie’s name inscribed on the side of their headstone, green lichen beginning to cloud the letters of his name: Albert Ernest Rennie. Killed in Action in France. August 5th, 1917. Aged 21 years.

I don’t recall hearing a word about this great-uncle, lost in the Great War. My brother Paul (with the better memory) does remember seeing Albert’s photo staring out from the top of Aunt Dora’s piano and asking her about the young man in the military uniform. “He was my brother, he died in the war.” And that was all she would say. Our half-sister Laura informs me Albert’s name appears on a plaque inside Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital at Orillia, built to honour the men killed in World War I. Our mother also worked there as a nurse, and almost forty years after Albert was killed, that’s where I was born and given the Rennie name. With the approach of another Remembrance Day, I feel compelled to learn more about Albert. How might I honour his short life? I know so little. It’s like walking down a narrow forest path and having it come to an abrupt end. Where to next?

I dive into searching the online Canadian war records and find that Albert E. Rennie enlisted with the 157th Overseas Battalion in February 1916 for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The enlistment paper tells me he was a nineteen-year-old farmer living at a Mrs. Watkins’s home on West Street in Orillia. At that time the town had an opera house, an “Insane Asylum” and Stephen Leacock, who lived at Brewery Bay where he dredged up Orillia stories for his classic Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town. I imagine this young boarder Albert, setting out from Mrs. Watkins’s each morning to work on a nearby farm. Leacock’s fictional Mariposa was drawn from Orillia, which he thought was like so many other small towns, “with the same square streets and the same maple trees and the same churches and hotels.” What was Albert thinking when he stepped into the registration office to sign the attestation papers with his stilted, compact script? Did he understand what “Terms of Engagement” truly meant? At this point in the war, perhaps he did. It had raged for almost two years with millions killed, a far cry from earlier expectations that the war would be over before Christmas 1914. The farm boy with the ruddy complexion was to be trained as a warrior. Would I trade places with him?

I came of age during the angry backlash to the Vietnam War and growing opposition to an expanding arsenal of nuclear weapons. Neil Young’s “Ohio,” John Lennon’s “Imagine,” Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son” and Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” were spinning on my turntable. During my mid-teens, my father suggested I join the military as had his father, older brother and one of my cousins. His pitch: “Good discipline, and a free education.” I didn’t give it a second thought. I was reading Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun. (The pacifist novel was inspired by the Prince of Wales’s visit to a Canadian soldier who had lost all of his senses and limbs.) My generation’s ethos was to question the glorification of war and the military-industrial complex and to “make love, not war.”

Albert came of age answering the call to fight for “King and Country.” By 1916 more than three hundred thousand young Canadians had signed up, many of them members of immigrant families from Great Britain. The colonial imperative was clear: stand up for Mother Country. Some were also drawn by adventure, others to a regular paycheque. After intensive training in Quebec and England, Albert and his Canadian troops were sent to the Western Front of Belgium and France. The front was oozing with mud so thick that it could add twenty-five kilograms to boots and uniforms. There were also the rat-infested trenches, a deafening roar of constant shelling, sniper fire, flame throwers and, to top it off, the risk of deadly mustard gas. Attacks and counterattacks came non-stop; the Western Front battle lines hardly budged over four years. On both sides the slaughter was horrific: sixteen million military and civilian deaths, twenty million wounded. Of the more than six hundred thousand Canadians who joined the Great War, sixty-seven thousand of them died and 173,000 were wounded. These are numbers so large, it is beyond our ken to grasp them.

There’s a note scrawled across Albert’s attestation paper indicating that he was transferred from the 157th Overseas Battalion to the 76th Battalion. I’ve located the regimental bugle call in the front pages of a battalion history; I slowly pluck out the notes on my guitar. G marching up an octave, back-stepping two notes, then, a return to G. It feels eerie to play this. Did these notes fill my great-uncle with courage, or dread? In April 1917 the Canadians experienced their most important victory at Vimy Ridge, the first major Allied victory of the war. Albert (now with the 18th Battalion) was part of the attack recorded in the Confidential War Diary of the 18th Battalion, now in the National Archives of Canada:

At Zero hour, viz 5:30 am, the advance was made. Simultaneously with the opening up of the Artillery Barrage the Battalion left the “Jumping-Off” trenches and attacked the German front lines.

French and British troops had previously tried in vain to take Vimy, but it was the Canadians who won this vital high ground. It was the first important victory of the war; it also gave the former colony a new sense of itself. Canadian troops were lauded by the British prime minister, David Lloyd George, who wrote in his memoirs, “They were marked out as storm troops; for the remainder of the war they were brought along to head the assault in one great battle after another.” The victory came at a terrible cost to the Canadians: 3,598 killed and 7,004 wounded. By early August, Albert and his comrades had moved on to a new battleground, preparing for the fight in trenches named Corkscrew, Cyclist, Cavalry and Cornwall. Military historian and author Mark Zuehlke pinpointed the battalion on the day Albert was killed: August 5th, 1917. “The Canadians were preparing for an attack in the area of Lens, France, against an objective called Hill 70. The attack was supposed to happen on August 4 but was pushed back by foul weather. So it went in on August 15. I suspect your uncle was killed by shellfire or on a patrol.”

Lens was the next big test for Albert and fellow Canadian troops. Its rail link supplied the Germans, and it possessed coal supplies in high demand for manufacturing. They prepared for the attack by practising on mock German positions, so that each man would know his job. The battalion’s war diary for August 5 speaks to the preparations, adding one poignant note: “Quiet day for the Battalion. The Battalion furnished carrying parties of 350 men for carrying Trench Mortar Batteries to their gun positions. Casualties numbering 1 o.r. [other ranks] killed and 3 o.rs. wounded.”

This reference stopped me in my tracks. It could very well be the death of twenty-one-yearold Albert E. Rennie, killed between battles during preparations for the push on Hill 70. Albert was gone but his mates were soon in the thick of it, and by August 15, ten Canadian battalions had attacked Hill 70, repulsing twenty-one counterattacks, finally claiming it on August 18. The Canadians took Hill 70, but not the larger objective of Lens. The war diary chronicle makes for a chilling read about what these soldiers faced and includes handwritten messages dispatched from the trenches:

From the information we have from two prisoners we have just brought in we have every reason to expect a counterattack tonight. I need a few S.O.S. flares.

Cannot something be done to keep the German planes away. What’s the matter with our air service?

Have only about 40 men in shape to carry on…can you send more reinforcements. Some shell shock cases carrying on.

Heavy barrage is required, every reason to believe they are coming over.

Part of my search to learn more about Albert Rennie has included renewing connections with Ontario cousins. I learn on the phone that Gail has named one of her sons Travis Albert. Her mother, Doreen, married my father’s older brother Hugh, who served during World War II. I think she’s smiling as she tells me that Hugh was also demoted for returning late from their honeymoon. I ask if she knows anything about Albert Rennie. “I just know they called him Ab.” Her mother-in-law Helen (Albert’s younger sister) did not speak about him. With so much loss tearing through families, perhaps it was too difficult to speak the pain.

Albert’s mother, Isabel, likely learned of his death in August 1917. Just two months later, she died of heart failure. She was only fifty-seven. Her heart was surely broken. It wasn’t until 1922 that Memorial Medals were given to the mothers and widows of dead soldiers. Albert’s were sent to his father, George. Aunt Doreen is the keeper of a silver cross that bears the sovereign’s crown, three maple leaves linked by laurel and the royal cipher “GRI” in the middle.

His name is stamped into the reverse side below his registration number: 643344. A purple ribbon is now faded and frayed.

Albert is buried not far from Lens, France, in the small village of Sains-en-Gohelle, beside hundreds of other Canadian and British troops. What if he had escaped the grim odds and returned home, fallen in love, planted crops and watched the Severn River flow past his family home? He most certainly would have tasted his sister Dora’s blue-ribbon baking—deep pies and butter tarts—and experienced her crushing bear hugs, the ones I came to cherish as a child. His sister Helen, my grandmother, would have graced his life with care and tenderness that mark all the stories I hear about her. On this Remembrance Day I will remember Albert and a life that might have been. After all, I am a Rennie.

He Never Made It to Europe

By Greg Dickson

Like Mark, my Great War odyssey began with a search for a great-uncle who never came home. His younger brother, my grandfather, survived Vimy Ridge and returned to Canada to raise a family. But Theo Dickson only made it as far as training camp in England before a sudden illness killed him at only twenty-two years of age. He left behind some wonderful letters and he was always fondly remembered by the family. His name is on the cenotaph in Vernon, but bodies were not sent home in those days and he was buried in a military cemetery in Wiltshire—too far away for family to visit or leave flowers.

I was determined to pay my respects. So in the spring of 2014, my wife Sheryl and I headed off for a holiday in the south of England. We saw Salisbury Cathedral and Stonehenge and the famous chalk hills. We visited Lawrence of Arabia’s cottage and grave in Dorset. And then we found Theo’s grave near Tidworth, a small town north of Salisbury. Tidworth is still a busy military base, and soldiers are everywhere. But just a little ways out of town, nestled in the Wiltshire Hills and surrounded by farmland, is a very peaceful cemetery.

I was worried that it would be one of those headstone jungles with crosses as far as the eye can see. But it turned out to be an intimate and well-cared-for place. The sun was shining and the hills were green and pretty in that English way.

I felt sorry for Theo, buried so far from his family. But he was lucky not to see the carnage of the Western Front. We left a Canadian poppy on his grave and took a moment to remember the brother who never made it home.

[Click here for A Message from the Canadian Letters and Images Project]

From Our Listeners

My Father’s Wounds: It is my belief that the effect that wars have on civilians often goes unrecognized. My story illustrates that point but I am certain my experience is mild compared to other children of returned World War soldiers. [Read more]

Mystery Soldier: William Rodger wasn’t a decorated officer, but he was a man who went to war and did his part. He should be honoured and not locked away in a box and forgotten about. [Read more]