The Gift of Salmon

British Columbia’s salmon producers were facing stiff competition from the US and Japan as war erupted. A recession had also created an oversupply of canned salmon, and the warehouses were filling up. As Geoff Meggs wrote in his book Salmon: The Decline of the British Columbia Fishery, the war generated a new demand from the British Army, creating opportunity for BC companies: “The First World War assured the canners the abundant profits of guaranteed markets, so they spent the time in intensive expansion, undertaking a new rush for the largely unharvested stocks of chum and pink salmon in the waters north of Johnstone Strait.”

During construction on the CNR in 1913 a disastrous rock slide at Hell’s Gate restricted Fraser River sockeye from moving up the river to spawn. It had an immediate impact on sockeye numbers and on the stocks four years later. The industry began chasing more pinks and chum to meet this sudden demand. Another challenge was getting the product to market. Many commercial freighters were seconded for the war effort, and prowling German submarines made shipping routes dangerous. This also increased the cost of getting cases of salmon across theAtlantic.

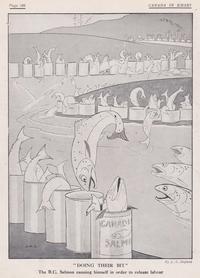

BC salmon was already a well-known commodity in Britain; companies had been shipping tinned salmon to workers since the 1870s, and by 1914 canned salmon was an important part of the British diet. It was also an ideal army ration. Precooked protein ready to eat right from the can. At the war’s onset, the provincial government donated 25,827 cases of pink salmon to the imperial authorities. In late1914 British Columbia’s commissioner of fisheries reported this gift of salmon would pay dividends:

Although the salmon had been designed by the Imperial Government for use in the relief of distress in the crowded industrial centres of the Old Country, after the usual strict inspections by British analysts and food inspectors, the War Office asked that 10,000 cases be placed at its disposal for rations for the troops. Letters from the trenches to the Department testify to the appreciation by the soldiers of this change of diet.

The War Office soon ordered another ten thousand cases. BC premier McBride also promoted salmon sales during his frequent journeys to England and by war’s end the sockeye, pink and coho fish pack had doubled in size and value. The fishery had also expanded dramatically, moving farther up the coast to Rivers Inlet, the Skeena and Nass Rivers and Vancouver Island.

Early in the war, Scottish immigrant Henry Bell-Irving, manager of Anglo-British Columbia Packing Company, was worried about an inadequate naval presence on the West Coast. There was only one coal-burning cruiser called the Rainbow, which was long in the tooth and short on crew, and two newly acquired submarines were having mechanical problems. Rumours of German cruisers lurking off the coast had many people nervous. Bell-Irving offered up three of the company’s vessels to the British Admiralty: Holly Leaf, Ivy Leaf and Laurel Leaf. They soon steamed to Esquimalt, were outfitted to launch torpedoes, then motored to Alert Bay where they patrolled the entrance to Johnstone Strait for the next nine months. The crew on each vessel consisted of the captain, engineer, cook, torpedoman and a signalman.

By war’s end a record eighty-seven packing plants were operating in BC. Many returning soldiers found work in the industry, but soon another recession hit and the industry took a nosedive. Some companies went out of business, others were bought by the handful of large companies that dominated the industry. However, British Columbia’s abundance of wild salmon provided sustenance when and where British, Canadian and Allied troops needed it most: in the trenches of a gruesome, relentless war.

There is more to be found about the salmon story at the Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site in Steveston (http://gulfofgeorgiacannery.com).

[To Top]