Art, Northwest Coast Aboriginal

ART, NORTHWEST COAST ABORIGINAL, is the rich, visual, cultural expression of the FIRST NATIONS people living in the coastal area of the Northwest portion of N America from Alaska in the north to the COLUMBIA R in the south.

Meaning and Context

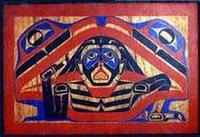

Archaeological discoveries provide evidence of thriving communities in large permanent villages up and down the coast dating back more than 8,000 years. Decorated tools and ceremonial items made of bone, stone, shell and wood and dating back about 2,000 years provide insight into the origins of classic Northwest Coast art. The mild climate, plentiful rainfall and wealth of food resources resulted in the development of stable communities where an elaborate and sophisticated culture thrived. Art of the Northwest Coast is an expression of spirituality, social status and ceremony. Iconographic images represent ancestral crest figures–KILLER WHALES, grizzly BEARS, WOLVES, EAGLES, thunderbirds, etc–from which a lineage descended. These are represented on TOTEM POLES, housefront paintings, talking sticks, ceremonial blankets, heirloom feast dishes and other eating utensils. The art also serves to make the supernatural world visible and is related to theatre, where powerful spirits are manifest in song and dance through the use of masks and other stage properties. The tendency in non-aboriginal, European society to distinguish between artistic and utilitarian concerns is absent from aboriginal culture, where art and spiritual ceremony pervaded every aspect of life. Even the most utilitarian objects were wonderfully wrought and decorated.

Northwest Coast art reflects the close relationship between the indigenous people and their environment. The great stands of red CEDAR in the coastal RAIN FORESTS were used to make masks, rattles, feast dishes and bentwood boxes, as well as houses, totem poles and CANOES. Yellow cedar, YEW, ALDER and MAPLE were used for ceremonial items, while HEMLOCK, DOUGLAS FIR and other species were used for a variety of implements and tools. Women made basketry items, capes, skirts, blankets, hats and mats from cedar bark, roots and branches, spruce root, bulrushes and SEAGRASSES. Decorative features also came from nature. Objects were decorated or inlaid with ABALONE shell, opercula, SEA LION whiskers, feathers, ermine skins, antler, teeth, bone and hooves.

The iconography of the art is bound to both this natural environment and the supernatural worlds of the different First Nations groups. Within the natural and supernatural are the distinct worlds of the sea, sky, land and spirit world. Supernatural beings interact with characters of the natural world. The recurring theme of transformation, linking the supernatural and natural planes of existence, is a key concept in the iconography of the art. Ceremonies, such as the Hamatsa of the KWAKWAKA'WAKW (Kwakiutl) or Tloquana of the NUU-CHAH-NULTH (Nootka), portray and dramatize the philosophies, spirituality and social structure of the specific group by calling on a well-known pantheon of characters. Such ceremonies demonstrate the significant relationship between art and belief systems. The rights to certain privileges are inherited or acquired through marriage. These privileges include stories, songs, dances and crests and ceremonial objects such as masks, rattles, blankets, feast dishes, etc.

Impact of Contact

The continuity of Northwest Coast cultures was disrupted by contact with Europeans. The post-contact period generally dates from the 1770s, when SPANISH and British explorers arrived on the coast. The material culture since that time reflects the profound changes, both positive and negative, brought about by the introduction of European materials, tools and values. From earliest contact First Nations artists incorporated commercial trade goods into their culture and artistic output. With the advent of the maritime FUR TRADE, iron became a popular trade item. Iron tools facilitated the carving process. The most popular trade good, textiles–particularly blankets–evolved quickly into ceremonial button blankets in which crest and other decorative border designs were sewn onto the blanket and outlined with trade buttons made of mother of pearl. Dance aprons were decorated with everything from deer hooves to thimbles.

Following the decline of the maritime fur trade due to the near extinction of the SEA OTTER, a second wave of newcomers arrived on the coast during the 19th century in the form of administrators, missionaries, industrialists, entrepreneurs and settlers. This new guard often deliberately sought to change the customs and beliefs of the First Nations people. The majority of missionaries and government officials promoted radical changes in lifestyle and sought to suppress the POTLATCH ceremonies, which were perceived as being diametrically opposed to their own economic views and spiritual beliefs. In 1862 the worst of a series of SMALLPOX epidemics swept through the population of the Northwest Coast, destroying whole villages and decimating the aboriginal population (see ABORIGINAL DEMOGRAPHY). On the heels of the smallpox epidemic came the official banning of the potlatch in 1884. For countless generations the potlatch had provided one of the main contexts for artistic production. At the same time, contact was a stimulus to artistic production, providing improved technology in the form of metal blades and new sources of wealth. As well, artists began producing items for sale to Euroamerican sailors, collectors and travellers. Early examples include ARGILLITE objects made by HAIDA carvers on Haida Gwaii (QUEEN CHARLOTTE ISLANDS). Religious icons commissioned by missionaries and model totem poles and canoes commissioned by ethnographers were the origins of the now flourishing art market. Along with the ethnographers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries came the TOURISTS. Steamboats plied the waters between Seattle and Alaska with frequent stops in First Nations villages. Northwest Coast artists responded to the tourist market and art was adapted to new purposes and new expectations, while maintaining links to the age-old artistic heritage.

Style

The style of Northwest Coast art is highly formalized and subtle, whether it is the two-dimensional flat designs on boxes, chests, bowls and screens or the carved designs on sculptured objects such as masks, poles and headdresses. Scholars usually distinguish between three style "provinces," each of which had distinctive stylistic similarities: the northern province (including the TLINGIT, Haida, TSIMSHIAN, GITKSAN, NISGA'A and HAISLA); the central province (including NUXALK, HEILTSUK, Kwakwaka'wakw and Nuu-chah-nulth); and the southern province of the SALISHAN-speaking groups. The style of Northwest Coast art was analyzed by the artist and art historian Bill Holm in his landmark study Northwest Coast Art: An Analysis of Form (1965). Holm identified certain essential design elements: the formline, a continuous flowing line that outlines the creature being represented; the ovoid, a slightly-flattened oval shape; and the u-form, lines drawn in the shape of the letter U. These elements are most strongly associated with the 2-dimensional arts of the northern groups. Southern groups share some characteristics of style with their northern neighbours, but they also employ their own graphic motifs. While these elements are present in most of the art, their use varies from group to group and from artist to artist. Styles in sculpture also differ from group to group, chiefly in the manner in which facial features–human, animal and mythical–are carved. Historically, 2 or more artists often collaborated. For example, pattern boards were prepared by male artists, then used by women artists who transferred the design to the weaving of the treasured CHILKAT BLANKETS in the north. Similarly, with Tsimshian and Kwakwaka'wakw button blankets, a male artist created the design while the female artist executed it. With Haida clan or chief hats, the weaving was completed by a woman, then passed on to a male artist for hand-painted decoration. By the close of the 20th century these gendered artistic boundaries were blurring.

Resurgence

The production of aboriginal art for ceremonial purposes, and for the curio trade, managed to survive the negative impact of contact with Europeans and the repressive government policies epitomized by the ban on the potlatch during 1884 to 1951. During the first half of the 20th century, several important artists were at work, including Charles EDENSHAW, a Haida man, and the Kwakwaka'wakw artists Charlie JAMES, Willie SEAWEED and Charlie G. Walkus, to name just a few. The legacy of knowledge and skills passed on by these masters enjoyed a resurgence beginning in the 1950s. In 1950 the Kwakwaka'wakw carver Mungo MARTIN was hired to restore totem poles at UBC's Totem Park. Martin later moved to the ROYAL BC MUSEUM to carry out a similar project, and he trained apprentices to repair and replicate totem poles. In 1967 the VANCOUVER ART GALLERY staged the "Arts of the Raven" show, a major exhibition that presented Northwest Coast aboriginal art as art instead of artifact. In 1970 the Kitanmaax School of Northwest Coast Indian Art opened at 'KSAN, providing an opportunity for young artists to develop. Amidst all this activity, a new generation of carvers and artists emerged, including Bill REID, Robert DAVIDSON and Freda Diesing (Haida), Doug CRANMER and Henry and Tony HUNT (Kwakwaka'wakw), Dempsey Bob (TAHLTAN-Tlingit), Norman TAIT (Nisga'a), Joe DAVID, Ron Hamilton, Tim Paul and Art Thompson (Nuu-chah-nulth), Susan POINT (Coast Salish), Walter Harris (Gitksan) and many others. Whether they are producing for ceremonial or community purposes, or for sale in the wider marketplace, aboriginal artists are recognized as being among the leading contemporary artists in BC.

Reading: Roy Carlson, Indian Art Traditions of the Northwest Coast, 1983; Wilson Duff, The Indian History of British Columbia, 1965; Marjorie Halpin, Totem Poles: An Illustrated Guide, 1981; Bill Holm, Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form, 1965; Peter Macnair et al, The Legacy: Continuing Traditions of Canadian Northwest Coast Art, 1980; Hilary Stewart, Looking at Indian Art of the Northwest Coast, 1979.