Chapter 7 - Hard Times and War

Hard times came to British Columbia during the 1930s. The Great Depression brought unemployment, poverty and business collapse. It was not until the outbreak of the Second World War that the economy improved. Then war brought suffering of a different kind.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION

For most British Columbians, the 1920s was a prosperous decade. Jobs were plentiful, industry thrived and the province grew rapidly.

The good times came to an end, however, with an abrupt crash. In October 1929, the stock exchange in New York City collapsed with echoes heard around the world. Businesses went bankrupt. People lost their life savings. At the same time, the prices of natural resources—lumber, minerals, and grain—began to fall. Canada, and particularly British Columbia, could not rely on the sale of its resources to support the economy.

Factories, mines and logging camps closed and workers lost their jobs. By 1933, almost one out of every three workers in Canada was unemployed. Those lucky enough to remain at work earned less money. Poverty and hardship was widespread. It was a time known as the Great Depression.

FAST FACTBy 1931, BC had the highest level of unemployment of any province in Canada—27 percent of workers did not have a job. |

LIVING IN THE JUNGLE

When they were unable to find jobs where they lived, many young men and women left home to seek work elsewhere. Without any money, they could not afford to pay for train tickets, food or hotel rooms. Instead they sneaked aboard freight trains and rode for free. This was called “riding the rails”.

When they came to a town, they begged for food going door to door. They slept outside in camps of unemployed people known as “jungles”. “In every town there was a 'jungle' where no one bothered you,” recalled one man who lived this life for several years. “This is where I cooked my meals over a jungle fire and had a short nap while waiting for the next freight train out.”

The wandering jobless tended to gather in cities, where they hoped work might be available. The police worried that so many strangers might cause trouble. City officials did not want to pay for taking care of them. As a result, the jobless were often hassled and hurried on their way.

|

In Their Own Words A WORKER

A worker from Vancouver Island writes the Prime Minister of Canada about the Depression: “Please pardon me for writing you, but I am in such a circumstance that I really do not know what to do. When will this distress amongst the people come to an end and how long will this starvation last? I am on the relief and only get 4 days work on the public roads. That is not enough for both of us to live on. Next came my land taxes. If I don't pay it this year, then the government of BC will have my 40 acres and I and my wife will be on the bare ground. Is that the way the Government will help the poor men?” [from L.M. Grayson & Michael Bliss, The Wretched of Canada: Letters to R.B. Bennett, 1930-35, Toronto, 1971, p.160] |

ON THE RELIEF

With so much unemployment, the government had to do something. Public assistance was a new idea in Canada in the 1930s. Unlike today, there was no social welfare, no employment insurance, nothing at all to help people who were down on their luck and had spent all their savings.

Faced with a crisis, government began a system of relief. When people became penniless, they could apply to their local government for assistance. It did not amount to much, but for thousands of families it was better than nothing.

FAST FACTIn 1933, at the peak of the Depression, about 15 percent of the entire population of Canada was getting relief. |

Another response by the government was to set up work camps for single men. They were located away from the cities. The men who stayed there received meals, a bed and 20 cents a day in return for working on road building and logging projects. There were more than 200 camps across British Columbia. No one was forced to go to them, but for many men it was their only way to feed and house themselves.

RUM RUNNING

One job that was always available for the adventurous was rum running. Between 1920 and 1933, it was illegal to sell or produce liquor in the United States. This period was called Prohibition. Americans who wanted a drink of liquor had to smuggle it into the country from outside—which is where the rum runners came in.

Rum runners were smugglers from British Columbia who carried liquor down the coast into the United States. In the dead of night they raced their speedy boats across Juan de Fuca Strait to hidden harbours in Washington State. There the cargo was picked up by trucks and carried to customers in the city. Sometimes large freighters loaded with cases of liquor anchored far offshore where the American Coast Guard could not seize them. Smaller boats rushed back and forth between the freighters on “Rum Row” and the shore, delivering their illegal freight.

The liquor traffic produced large profits and soon attracted big-time criminals. Rum runners fought with one another for control of the business. The Coast Guard did its best to chase down the boats and arrest the smugglers. It was a bit like the Wild West at sea, and rum runners had to be people who liked danger and adventure.

When finally the American government ended Prohibition in 1933, there was no longer a need for smuggling and the rum-running era ended.

PROTEST

As the Depression grew worse, the unemployed began to grow angry. They demanded answers to their problems. They resented being cooped up in relief camps which they said were no better than jails. They did not like being treated like criminals when their only “crime” was being jobless.

In April 1935, an army of unemployed left the interior camps and marched down to Vancouver. They demanded “work and wages”. From Vancouver the protestors set out riding the rails across Canada. They planned to carry their demands to the prime minister in Ottawa, and so the protest was called the On-To-Ottawa Trek.

As the train rolled through British Columbia and the Prairies, it picked up more protestors along the way. In Regina, the capital city of Saskatchewan, things came to a head. Police ordered the train to halt, while a small delegation of protestors went ahead to Ottawa to talk with Prime Minister R.B. Bennett. Bennett was not sympathetic. He sent the delegation away empty-handed.

Back in Regina, the protest turned violent. At a huge outdoor rally, police charged the crowd, swinging clubs and making arrests. One police officer was killed; many protestors were injured. The so-called Regina Riot marked the end of the On-To-Ottawa protest.

BLOODY SUNDAY

There was no end in sight for the Depression. Back in Vancouver, unrest continued. In April 1938, the government closed its work camps. Men who were unemployed and not married could not receive relief. The government did offer to pay for these men to travel to other provinces to look for work. But there was no work, so protestors gathered in Vancouver instead.

On May 20, about 1,200 men entered the city post office, the art gallery and a downtown hotel. They sat down on the floor and refused to move until the government did something. Such a large number of people could not be arrested. It would fill the jails to overflowing. Instead, officials decided to wait and see what happened.

At last the police lost patience. Early on the morning of June 19, RCMP and city police moved in to evict the sit-downers. Some left peacefully, having made their point. At the post office, however, police used tear gas and clubs to drive protestors into the street. Hundreds were injured. Furious at the police, a crowd marched through downtown streets breaking store windows.

At a huge outdoor rally in a downtown park, unemployed people and their supporters condemned police violence. “We want something done for these people,” one speaker declared, referring to the unemployed. The government responded with emergency relief, and tempers cooled.

|

FAST FACT Bloody Sunday, as it was called, ended with thousands of dollars damage, hundreds of people injured, and 22 protestors in jail. |

FISHING STRIKE

Not all protest during the Depression was violent. Many workers staged peaceful strikes to try to improve their wages and working conditions. One of the most important strikes in British Columbia during the 1930s was the fishing strike of 1938.

Fishers sold their catch each summer to the canneries that were located all along the coast. The owners of the canneries were used to paying whatever they decided for the fish. In 1938, the owners suddenly reduced the price of salmon. This time, the fishers did not accept. Instead, they tied up their boats and refused to produce any fish.

It was a bitter strike. In many small fishing communities, the only store was owned by the canning company and these were closed to strikers. Owners brought in other fishers to try to keep a supply of fish coming into the canneries. At the height of the strike, dozens of boats got together and traveled down the coast to Vancouver where they entered the harbour in two long lines. This defiant action carried the protest right to the heart of British Columbia's largest city.

As more and more fishers joined the strike and tied up their boats, the canners had to give in. An agreement was reached that gave fishers a better price for their salmon. It was the first time that fishers on the Pacific Coast had acted together to challenge the power of the owners.

|

BC People AT HOME ON A BOATMost children in British Columbia lived in the cities, but one family spent their time cruising the coast in a small (7.6 metres) boat called the Caprice. The five Blanchet (blon-SHET) children— Frances, Peter, Betty, David and Joan—lived on the boat with their mother, who was called Capi because she was the captain. Every summer in the 1930s, the Blanchets left their house in town to roam the inlets and islands of the coast, looking for new things to see and do. They were especially interested in visiting the village sites of the Aboriginal people, where totem poles and cedar houses stood silently in the forest. The boat was not large, but somehow they found space for everyone. At night, when they tied up to shore, the family dog warned them if a wandering cougar or bear got too close. Later in her life, Capi Blanchet wrote a book, The Curve of Time, about life aboard her boat. It is a wonderful story about a footloose family and its adventures among the people and animals of the coast.

The Blanchets on one of their summer excursions in the 1930s. From left to right, Frances, Peter, Betty, David, Joan and Capi. Raincoast Chronicles Six/Ten (Harbour, 1983)

|

A NEW PARTY

During the Depression, people all across the country decided that the political system needed a change. Some of these people took part in protests like the one in Vancouver. Others decided to form new political parties.

In 1933, a group of workers, farmers and reformers got together at Regina, Saskatchewan, to create a new party. They called themselves the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, or CCF for short.

The CCF wanted a much larger role for government in the lives of Canadians. It blamed banks and large corporations for the Depression. CCFers wanted to make sure that all Canadians, rich and poor alike, had jobs, education and health care.

The CCF had a lot of support in British Columbia. It became the second most popular party with voters. In 1961, the CCF changed its name to the New Democratic Party (NDP). It is still active in politics today.

|

BC People GRACE MACINNIS

(1905-1991) MacInnis herself decided to run for election. In 1941 she became a member of the BC Legislature, one of fourteen CCF candidates who won seats that year. Both in and out of the legislature, she continued to be an active leader of the party. When Angus died in 1964, she decided to run for a seat in the federal Parliament. By this time the CCF had become the New Democratic Party (NDP). MacInnis won a Vancouver riding for the NDP, becoming the first British Columbia woman elected to Parliament. She kept her seat until 1974, when poor health forced her to quit politics. |

CREATING THE WELFARE STATE

Eventually the worst of the economic crisis passed. But no one who lived through the Depression would ever forget the hard times. Canadians were determined that never again should so many people suffer so much hardship.

The Depression changed many peoples' minds about the role of government in society. It showed that many people could lose their livelihood through no fault of their own. Canadians came to accept that government had a role to play helping people when times were bad.

In the years that followed, a number of government programs were created to help the poor, the sick and the jobless. Taken together, these programs are what is known as the welfare state. They include health care insurance, pension plans and schemes to help the unemployed. The welfare state tried to create a safety net so that no one could lose everything they had because of sickness or job loss.

|

BC People DUFF PATULLO

Premier Duff Pattullo talks with a future voter in 1941. Pattullo was premier of British Columbia from 1933 to 1941. City of Vancouver Archives PORT- P.817

In the middle of the Depression, British Columbia voters went to the polls. They voted out the old government, which they blamed for not doing anything about the economic crisis, and they turned to Duff Pattullo, leader of the Liberal Party. Pattullo was a politician from Prince Rupert. He came to office with new ideas for coping with the Depression. He thought that the government should play a larger role in the economy, especially to help the poorest members of society. He put unemployed people to work building roads and bridges, and he began a system of medical insurance. Pattullo was disappointed that the federal government in Ottawa would not give him enough money to do even more to boost the economy. He called himself “a British Columbian Canadian,” meaning that he put the needs of his province first. “We are an empire in ourselves,” he said, “and our hills and valleys are stored with potential wealth.” He spent much of his time as premier quarrelling with the government in Ottawa. Pattullo remained premier until 1941. The Pattullo Bridge over the Fraser River is named for him. |

WORLD WAR, AGAIN

In 1939, World War Two broke out. Once again, the battleground was Europe, where Germany and Italy, known as the Axis, fought against Great Britain, France and their allies. And once again, Canadians volunteered by the thousand to fight for the Allies.

War went a long way towards solving the country's economic problems. The number of people who were unemployed fell as men and women hurried to join the armed forces. The demand for war goods increased. Industries geared up to produce ships, airplanes, munitions, building materials and many other items.

Women were called on to step into the jobs left by their brothers and husbands who had gone to war. Women went to work in war industries, on the farm and on construction projects. In peacetime, this kind of work was considered unsuitable for women. During wartime, they kept the economy going.

FAST FACTBy 1945, more than 43,000 Canadian women had joined the armed forces. |

More than that, women were accepted into the Canadian armed forces for the first time. The army created the Canadian Women's Army Corps, followed by the navy and air force.

Related Links:

The Second World War

|

In Their Own Words EMILY CARRThe artist Emily Carr wrote about her feelings at the news that war had begun. “It is war, after days in which the whole earth has hung in an unnatural, horrible suspense, while the radio has hummed first with hope and then with despair, when it has seemed impossible to do anything to settle one's thought or actions, when rumours flew and thoughts sat heavily and one just waited, and went to bed afraid to wake, afraid to turn the radio knob in the morning.” [from E. Carr, Hundreds and Thousands, Toronto, 1966, p.233] |

THE HOME FRONT

The war caused shortages in the everyday life of Canadians. Products such as rubber, gasoline, iron, and many food items were in demand for the war effort. Back at home, consumers had to go without.

In 1941 rationing became a fact of life for Canadians. Every person was given a ration book. It contained a number of coupons that could be used to obtain things like coffee, milk, sugar, butter and so on. Gasoline, which was so vital for the war, was also rationed, along with rubber tires. Many people just stopped driving for as long as the war continued.

No one was allowed to waste anything. People tried to grow as much of their own food as they could. Children went door-to-door collecting scrap metal that might be used for making military equipment. The war was an all-out effort.

WAR IN THE NORTH

On December 7, 1941, Japan launched a surprise attack on an American naval base in Hawaii called Pearl Harbour. Canada, along with the United States, immediately declared war on Japan. It was truly a world war now.

The Americans worried that Japan might invade North America through Alaska. In order to get troops and supplies to the North, the Americans decided to build a highway across the top of British Columbia.

The Alaska Highway, as it came to be called, ran from Dawson Creek to Watson Lake in the Yukon. It was built very quickly by thousands of American soldiers. After the war it was taken over by Canada. Today the Alaska Highway is still an important route through northern British Columbia.

THE GUMBOOT NAVY

When World War Two began, Canada's navy was centred on the Atlantic Coast. The coast of British Columbia was defenceless against attack or invasion. What the coast did have was a lot of fishers, and no one knew the area better. The government decided to transform the fishing fleet into a navy.

Officially they were the Fishermen's Reserve, but everyone knew them as The Gumboot Navy. In total, there were 42 fish boats and 975 fishers. They were given guns and sent out in all kinds of weather to look for enemy submarines.

After the attack on Pearl Harbour, people in British Columbia had a real fear of an invasion by Japan. While the invasion never came, the Gumboot Navy took seriously its role as the first line of defence. By 1944, as the threat of invasion eased, the force disbanded and the crews went back to fishing.

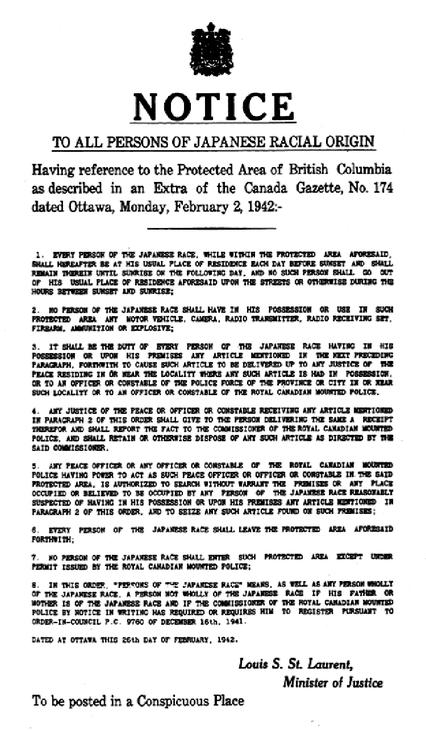

TREATMENT OF THE JAPANESE

Japanese people were never completely welcome in British Columbia. Strict limits were set on the number who were allowed to enter from Japan. Like other Asian newcomers, and the Aboriginal people, they were not allowed to vote, or to hold certain jobs.

When war began, this suspicion deepened. Many British Columbians wondered how Japanese Canadians would behave now that Canada was at war with Japan. There was a great fear on the Coast that Japanese war ships might invade across the Pacific. If that happened, would the Japanese living in British Columbia be loyal to their new home, or their old?

At the outbreak of war there were about 23,000 people of Japanese background living in British Columbia. Most of these people were citizens of Canada. Many had been born in British Columbia. They considered Canada to be their home. So they were shocked early in 1942 when the government announced that all people of Japanese background living along the coast of British Columbia had to move away.

Over the next few months, about 20,000 people were forced from their homes. They were loaded on trains and sent to live in camps in the interior of the province. Some were sent to the Prairies and Ontario. They were treated like prisoners and not allowed to move around without written permission. Once they were gone, the government sold all their possessions.

As it turned out, Japan did not invade. After the war, Japanese Canadians were allowed to return to the Pacific Coast. Prejudice against them slowly weakened. In 1949 they received the right to vote, like every other citizen.

Finally, in 1988, the federal government admitted that the treatment of Japanese Canadians during World War Two was unjust. It apologized and agreed to pay compensation to every person who had to move during the war. It also set up a fund to support the Japanese-Canadian community.

|

In Their Own Words WE WERE GOOD CANADIANS Joy Kogawa was a young girl who was removed from Vancouver with her family and sent to live in the Interior. Many years later she wrote about her experience: "It is hard to understand, but Japanese Canadians were treated as enemies at home, even though we were good Canadians. Not one Japanese Canadian was ever found to be traitor to our country. Yet our cameras and cars, radios and fishing boats were taken away. After that our homes and businesses and farms were also taken and we were sent to live in camps in the mountains. Fathers and older brothers and uncles were made to work building roads in the Rocky Mountains. If you ever drive through these beautiful mountains, you may ride over some roads made by Japanese Canadians." From Naomi’s Road, Joy Kogawa (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1986). |

THE WAR IS OVER

On August 14, 1945, Canadians celebrated V-J Day, Victory Over Japan Day. In every city and town across the country, people poured into the streets, honked their car horns and threw paper streamers into the air. After six long years, it was the end of World War Two, and the beginning of peace.

The previous fifteen years had been hard ones. First there was the economic crisis of the Great Depression when so many people went jobless, losing their homes and life savings. The Depression was followed by war, when everything had to be sacrificed to ensure victory.

As they celebrated a return to peace, British Columbians hoped for a return to prosperity as well. After so much turmoil and suffering, they just wanted life to be normal again.