Chapter 6 - Growth and War

It was a period of rapid economic growth in British Columbia and it was concentrated in the southwest corner of the province, the area that came to be known as the Lower Mainland.

Related Links: History of Fraser Valley Communities

BOOM TIME

At the beginning of the twentieth century, British Columbia enjoyed a period of rapid expansion. Newcomers poured into the province. Between 1881 and 1911, the population increased from 50,000 to 392,000 people.

Most of the newcomers settled in British Columbia's three main cities: New Westminster, Victoria and Vancouver. By the turn of the century, these were all growing communities with the latest modern conveniences: electric streetcars, electric lights, telephones and fresh drinking water.

THE ROYAL CITY

British Columbia's first city was New Westminster. It was founded in 1859 to be the capital. It is the oldest Canadian city west of Ontario.

New Westminster is located on a hill overlooking the Fraser River not far from its mouth. It used to be the site of an ancient Aboriginal village. The capital of the province moved to Victoria in 1868, but New Westminster continued to grow as an economic centre. Steamboats traveling on the river stopped there. The salmon canning industry flourished nearby. Several sawmills were built to make lumber out of logs from the surrounding forest.

East of New Westminster lay the fertile valley of the Fraser River. As this land filled with settlers growing vegetables and fruit and raising dairy herds, the city became the main market where the farmers brought their produce for sale.

A century ago, cities were mostly wood. The buildings were made of lumber, and even the sidewalks were plank. Fire was a constant threat. On the night of September 10, 1898, fire started in a steamboat moored on the waterfront. Flames spread from the boat to a pile of hay stored on the dock. From there the fire swept through the centre of the city, destroying all the buildings in its path. By morning, most of downtown New Westminster lay in ashes.

But fire could not destroy the spirit of the residents. Immediately they began rebuilding. Donations came from across Canada. Within a year most of downtown New Westminster was rebuilt and the Royal City was back in business.

FAST FACT

Originally the community was called Queensborough, after Victoria, Queen of England. The Queen herself preferred New |

|

In Their Own Words THE COLUMBIANThe local newspaper, The Columbian, reported on the blaze: "All up McKenzie, Lorne, Begbie, Alexander and Eighth streets the flames rushed in a mad chase. Thus it was that the whole south side of Columbia Avenue burst into flames practically at the same time. Merchants who had made desperate efforts to save their private papers were drawn from their stores in a rush for life. The Hotel Douglas became a howling volcano of flame a few minutes after it was first noticed to be on fire. The guests had ample warning though, and all had escaped from the building though few had more of their belongings than what they stood up in. A sheet of living flame swept across the street and burst in the windows of the splendid Hotel Guichon. The noise was deafening. Above the roar of the flames, repeated explosions could be heard as the fire reached the explosives stored in the warehouses of Columbia and Front streets. The earth trembled with repeated shocks and the crash of breaking glass joined with the jar of falling walls to make the night a horror." From The Columbian, September 17, 1898. |

Related Links:

Life in the City of New Westminster

ELECTRIC STREETCARS

For many years, travel around the Lower Mainland was by horseback or wagon on dirt roads littered with stumps and boulders. In rainy season, the roads turned to impassable mud.

In 1891, an electric railway opened between New Westminster and Vancouver. It was called an interurban railway because it operated between two urban communities. At the time, it was the only interurban in North America. Interurbans ran on steel tracks, just like a steam railway, but they were powered by electricity passing through overhead wires. Each train connected to the wires by trolley poles.

The Westminster and Vancouver Tramway was just the beginning. Soon there were electric trains running between Vancouver and Richmond, and in 1910 a line opened to connect New Westminster out the Fraser Valley 100 kilometres to the town of Chilliwack. Farmers used the line to carry their produce to the larger centres. Special trains raced in daily from Valley farms carrying milk for urban households.

Meanwhile, electric streetcars were also put into operation in the major cities. Victoria was first. In February 1890, Car #1, loaded with dignitaries, rattled down Store Street. It was the official opening of the third street railway in Canada, the first in British Columbia. Four months later, Vancouver opened its street railway, followed by New Westminster the next year.

Street railways had an important effect on the shape of the modern city. They were the first means of moving large numbers of people quickly and cheaply. People no longer had to live close to where they worked. They could live at a distance from their jobs and commute to work by streetcar. Wealthier residents left the inner city altogether, moving to suburbs away from the hustle and bustle of downtown.

|

FAST FACT The first electric streetcar in Victoria could reach a speed of 15 kilometres an hour. |

CAPITAL CITY

Victoria has always had a reputation as a British city. Many fur traders from the Hudson's Bay Company retired to farm there. In the days of the colony, most government officials came out from England and many stayed on with their families. Their palatial homes were the centre of fashionable society.

Another British influence was the naval base at Esquimalt, next door to Victoria. For many years it was the headquarters of the British navy in the Pacific Ocean. Warships visited the harbour to take on supplies and allow the sailors some time on shore. In 1910, the Canadian navy took over the base and today Esquimalt remains a naval centre.

The arrival of the railway in Vancouver in 1886 attracted industry to the mainland city. As a result, Victoria took second place as an economic centre. But it held centre stage as the capital of the province. In 1898, the new Parliament Buildings opened. They featured marble walls, stained-glass windows, mahogany carvings, and on the top, a golden statue of Captain George Vancouver. Today the buildings remain the place where the government meets.

|

BC People

|

ASIAN NEWCOMERS

Among the newcomers pouring into British Columbia were thousands of Chinese people. They came to work on railway construction, in the salmon canneries and coal mines, and as merchants and farmers.

For the most part the Chinese newcomers lived together in their own neighbourhoods, called Chinatowns. They wanted to be in familiar surroundings, close to relatives. Victoria had the first Chinatown in Canada, and until 1910 it was the largest. Vancouver also attracted many Chinese. Its Chinatown surpassed Victoria's as the largest in Canada and one of the largest in North America.

The Chinese were not the only newcomers from Asia. Immigrants from Japan and India also settled in their own areas of the city.

By 1911, people from east Asia made up eight percent of the population of British Columbia. This was not a large number, but it was enough to raise fears among the white majority. White British Columbians believed that people from Asia, because of their different customs and languages, would not mix with the rest of society. Workers were afraid that the newcomers would take their jobs. Some white people believed that if Asian immigration continued, the newcomers would soon control British Columbia society.

FAST FACTIn 2006 the government of Canada admitted the head tax was an unjust policy and apologized for it to the Chinese-Canadian community. |

In response to these fears, the government made laws to restrict immigration to British Columbia from Asia. In 1885, a new tax was introduced requiring Chinese to pay $50 each to enter Canada. This was the so-called “head tax”, and over the years it rose to $500. No other immigrant group had to pay such a tax. Then, in 1923, the government halted all immigration from China. Similar restrictions were put in place against newcomers from India and Japan. At the same time people of Asian background were not allowed to vote or to hold certain jobs.

The restrictions against Asians remained in force until 1947.

|

In Their Own Words A CHINESE HOUSEBOYWing Wong, who arrived in Vancouver in 1912 to work as a houseboy, described his life: "I was small in those days, twelve or thirteen. I studied after school and then I did my work: chopping wood, bringing up coal, house cleaning, taking care of the furnace, washing dishes. Just to get my room and board."

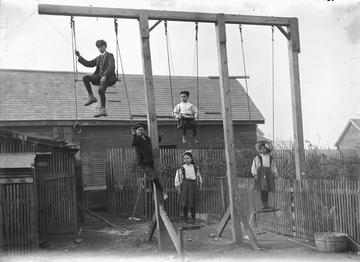

Many young people from China came to British Columbia as servants— houseboys and maids—for white families. This photograph shows a houseboy with his family in Vancouver about 1900. BC Archives B-03779

|

|

History Mystery WHO MURDERED JANET SMITH?

Janet Smith. City of Vancouver Archives

It is one of the most troubling unsolved murder cases in Vancouver history. On the morning of July 26, 1924, someone shot and killed Janet Smith at her home in the Shaughnessy neighbourhood of Vancouver. Smith was a twenty- two-year-old nanny who came from Scotland to look after the children of a wealthy family. Who would want to harm her? Police became suspicious of the family’s Chinese houseboy, Wong Foon Sing. He was the only other person in the house at the time of the murder. There was no evidence pointing in his direction, but people were prejudiced against him mainly because he was Chinese. At one point police kidnapped Wong and tortured him to get a confession. When he would not confess, Wong was arrested and thrown in jail. But at his trial, the jury let him go for lack of evidence. Angry at the treatment he had received, Wong returned to live in China. Meanwhile, no one ever was convicted of the murder of Janet Smith. |

PACIFIC PORT

Few cities have appeared as suddenly as Vancouver. In 1881, a few dozen loggers and sawmill workers lived along the shore of Burrard Inlet. Then the railway arrived, followed by merchants and builders of all descriptions. By 1900, the population numbered 27,000 and was growing fast. Where a lonely forest once stood, there were solid stone buildings, paved streets, and houses spreading in all directions. “Chop, chop, chop. The forest vanished, and up went the city,” wrote novelist Ethel Wilson.

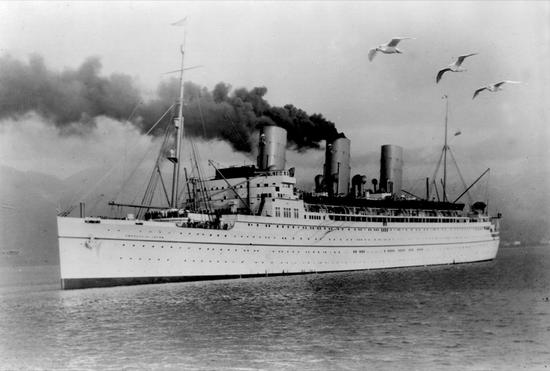

Vancouver faced in two directions at once. It looked outward across the Pacific to the Orient and Australia where there was a ready market for its products. Vancouver was a busy port, welcoming ships from around the world. The Canadian Pacific Railway operated a fleet of ocean-going steamships. These vessels, called the Empress ships, set a new standard of speed and elegance. They steamed between Vancouver and the Orient, carrying passengers, mail and cargo of all types. Vancouver's harbour shipped lumber, salmon, coal, and other minerals to many countries.

At the same time, Vancouver looked to the interior. The CPR, and the other railways that followed, connected the port city to the rest of the continent. Goods came by ship to be loaded onto the trains that carried them across the mountains to the Prairies and beyond.

One especially exotic product was silk. It was imported on the Empress ships from the Orient, then loaded on trains for shipment to eastern Canada and the United States. Raw silk spoils very quickly. Speed was crucial. When a train carrying silk was passing, all other traffic on the railway stopped.

Vancouver was more than a port city. It was also the centre of the province's industrial activity. The large salmon canning companies had head offices there. The lumber industry provided more jobs than any other industry. By 1915, three railway lines from across the continent entered the city. Three quarters of all the goods manufactured in British Columbia were made in Vancouver.

Automobiles began appearing on Vancouver streets as early as 1904. The first gasoline car was purchased by John Hendry, a sawmill owner. They rumbled through the streets at 10 kilometres an hour, coughing smoke and frightening the horses. For some years, only the wealthy could afford one. By the 1920s there were enough motorcars so that the city's first traffic light had to be installed.

|

BC People

JOE CAPILANOJoe Capilano was a prominent First Nations leader, and his wife Mary was a noted storyteller. They were members of the Squamish people, who live in North Vancouver. This photograph shows Joe Capilano in 1906, when he led a group of Aboriginal leaders to London, England. They wanted to explain to the King of England why the Aboriginal people believed they had been pushed off their land by white settlers. But the British government told the delegation that its complaint was a matter for the government of Canada to settle.

|

WORLD WAR ONE

World War One began in 1914 and lasted four years. The fighting occurred far from Canada in Europe, where the armies of Britain, France and Russia struggled against the German and Austrian empires. Many Canadians felt strong ties to Britain and volunteered in large numbers to join the conflict.

At first the war seemed like a big adventure. Young soldiers hurried to sign up because they feared it would all be over before they could see any action. Only slowly did the true horror of the conflict sink in. Far from ending quickly, the war dragged on year after year. Millions of lives were lost, and millions more soldiers were badly maimed.

After three years of war, Canada was running short of volunteers willing to fight. In 1917, the government passed a law forcing young men who were not married into the army. This was called conscription, and it was unpopular with many people who for one reason or another opposed the war.

British Columbia was divided by the impact of war. In some ways the province prospered. Shipyards hummed with activity, as many vessels were needed for the war effort. The conflict created a huge demand for raw materials produced in British Columbia: copper, lumber, coal and wood.

But the cost in human lives was high. British Columbia had more volunteers per capita than any other province in Canada. By war's end, 6,225 British Columbians were dead, and more than 13,000 more suffered horrible wounds.

|

BC People GINGER GOODWIN

(1887-1918) |

|

BC People PREMIER MCBRIDE

Richard McBride was born in New Westminster and worked as a lawyer before he got into politics. He became leader of the Conservative Party and was elected premier in 1903. He was thirty- two years old, the youngest person ever to become premier. Voters called him “Handsome Dick,” and he was very popular for his friendly, open manner. McBride led his party to victory in four elections. In 1912 he won a knighthood from the King of England, making him the only premier in Canadian history to be called “Sir.” McBride was successful in attracting investors to the province. He made large grants of land to railway, logging and mining companies. His years as premier are sometimes called the “Great Potlatch” because he gave away so many of British Columbia’s natural resources. |

WOMEN AND THE WAR

The outbreak of World War One opened new opportunities for Canadian women. With so many men away in the armed forces, women were called upon to take their place in the work force.

Up to this time, most women had worked in the home, raising children and looking after the household chores. Women with jobs had worked as schoolteachers, nurses or at one of a few other traditional jobs. Most of the work world was closed to them.

This changed with the war, and the urgent need for workers in the factories and war industries. Women became airplane mechanics and munitions makers. They took jobs in business offices. Some went overseas to serve in the front lines in the medical corps or as ambulance drivers.

Their new importance in the work world gave women new influence in the political world as well. Until the war, only men were allowed to vote in elections. That changed in 1917 when British Columbia women received the right to vote in provincial election. The next year the same right was extended to federal elections.

Changes to the law meant that women could run for elected office. In 1918, Mary Ellen Smith of Vancouver became the first woman anywhere in Canada elected to a provincial parliament. A few years later she became a cabinet minister in the government, another first.

Of course, this right was not won by all women. First Nations women and women of Asian background were still denied the vote, along with their men folk.

KILLER EPIDEMIC

With the end of war came a new killer. An outbreak of deadly influenza began in Europe and spread to Canada with returning soldiers. Before it was over, the flu killed 21 million people worldwide, 50,000 in Canada.

The first cases appeared in British Columbia in October, 1918. People easily caught it from each other, so health officials asked everyone to avoid public places where they might be infected. Schools, shops, churches and theatres all closed. All public meetings were banned. Hospitals filled to overflowing. People wore masks over their faces to keep from spreading germs. Doctors were powerless. There was no drug or vaccine; patients could only stay in bed hoping to get better.

By the time the epidemic faded away in the spring of 1919, about one out of every three people had been sick. In Vancouver alone, 900 people died. It was the worst public health disaster since the smallpox epidemic many years earlier.

FAST FACTIn BC, about 4,000 people died in the flu epidemic. |

THE NEW CITY

Industry and immigration together created a new kind of city. New Westminster, Vancouver and Victoria were very unlike the small farming and trading communities of British Columbia's early years. They were bigger, noisier, richer and more varied.

The new city was divided into neighbourhoods of rich and poor. Immigrants from China, Japan and India lived in their own sections. For some, the city presented great opportunities. For others, it brought poverty and injustice.

One of the biggest changes was the rapid growth of the Lower Mainland. When British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871, not many people lived in that part of the province. Then, with the arrival of the railway, the Lower Mainland boomed. By the 1920s, Vancouver and its surrounding area was home to about half of all the people who lived in British Columbia, and its industries were producing most of the wealth.